We're counting down the days to the start of the 2017 Lucas Oil Pro Motocross opener at Hangtown on May 20 with a look back at some of the most memorable motos in AMA Motocross history. This summer, you can watch all 24 motos on all of your devices on NBC Sports Gold. Today, we're looking at the 1979 Hangtown race and what happened after.

The second 250cc moto of the 1979 Hangtown National was your typical seventies motocross race. It was the Dirt Diggers North Motorcycle Club’s 11th Annual Hangtown Classic, but the first at the new Prairie City Off-Highway Vehicle Park, the same site that is used today. It was packed, of course, and of course Bob “Hurricane” Hannah won—he was the defending 250cc AMA Motocross Champion and easily the best American motocross rider of all. The Yamaha factory rider was followed by his longtime rivals Marty Tripes and “Jammin’” Jimmy Weinert.

But the second 250cc moto had a few other little things that were atypical of motocross at the time, like local hero Danny “Magoo” Chandler having the chain come off his Maico, and Kawasaki support rider Larry Wosick hitting a spectator who ran across the track, costing him a solid fifth-place finish. Tripes’ pipe broke in half on his works Honda RC250, and even Hannah had problems when dirt got clogged up between his rear brake pedal and caused him to stall. Hannah got going in time to hold on to the lead and the win.

But it’s what happened after the moto that made Hangtown ’79 one of the most memorable motos in American motocross history. That’s when a privateer Maico rider named John Roeder, from Chico, California, walked up to AMA referee Butch Lee and handed him a cashier’s check for $3500 and claimed Marty Tripes’ works bike. It was a legal move, according to the AMA rulebook of the time, and the price adjusts to about $12,000 in today’s dollars.

According to an epic Cycle (August 1979) feature titled, “The Week Motocross Almost Died,” the author Dave Hawkins explained the AMA’s claiming rule this way: “If you were a privateer, you might see the rule differently: as a guarantee against victory-by-technology, as a solemn covenant on open and fair competition, as the privateers ultimate weapon against the factory oligarchies and their special equipment.”

In 1976 the rule dogged Team Honda’s Marty Smith all season long, as his former teammate Mickey Boone kept trying to claim Smith’s RC12.

This wasn’t the first time Roeder had tried to claim a factory bike. At the Oakland SX earlier that season (the race Weinert won with a paddle tire) Roeder came with a personal check but didn’t qualify for the race, and thus couldn’t claim a bike. But he talked another privateer named David Bowman who did qualify for the night program, but not the main, into making a claim on third-place finisher Steve Wise’s works Honda. But AMA referee Mike DiPrete would not accept the third-party check from Bowman, so Honda got to keep the bike.

From that point on the factories came up with a strategy to at least try to keep a bike if it’s claimed, and that was to have all of their riders in the race file claims against a motorcycle too. That way the AMA would at least have to hold some kind of draw, and the odds were better if one privateer’s claim was one of 10 or 12 chances. The AMA also made a tweak: only a rider in the main event could claim a bike off the podium, and with factory teams fielding four or five riders back then, the main events were practically full of factory riders. So Roeder waited for the opening round of the outdoor nationals at Hangtown, where the chances of qualifying would be much easier. He was committed to his purpose.

“I wanted to make a point,” said Roeder. “I’d like to keep the factories honest. The claiming rule was put there for a purpose—to make it fair for the privateers. The factories say they use these exotic bikes for development of next year’s model … but all I can say is Husqvarna and Maico don’t race $100,000 motorcycles to develop them.”

Roeder was right, but that was because the European brands had long been left behind by the Japanese OEMs. Maico was in its death throes as a company, and Husqvarna was not the strong competitor it once was. Other brands—CZ, Bultaco, Monesta, Puch—had virtually disappeared from American motocross altogether.

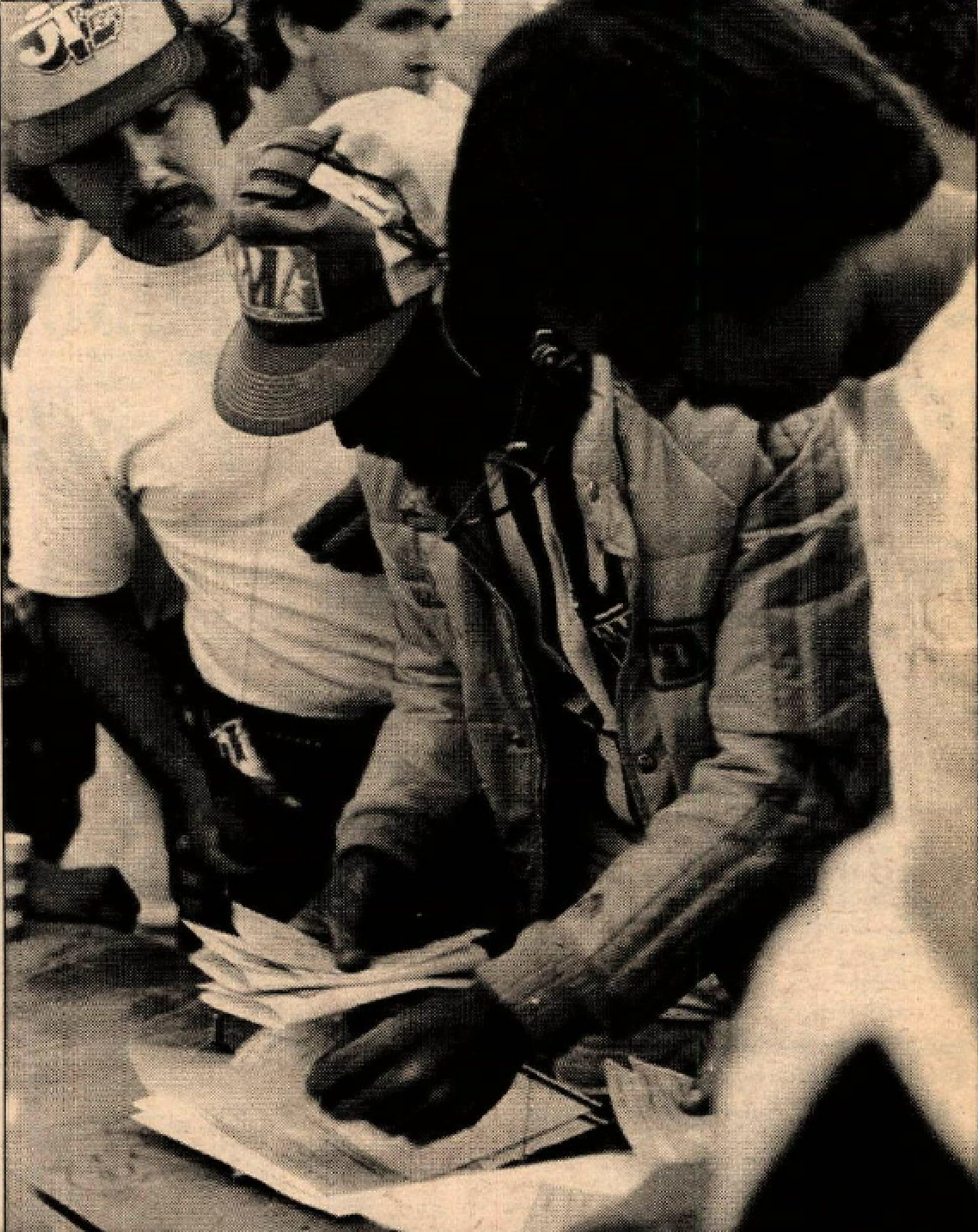

So at Hangtown, where he raced against Tripes in the second 250cc heat race, but failed to advance to the main, Roeder made his claim for Marty’s machine with just 20 seconds to spare before the half-hour protest/claim period was over. The four Japanese factories were ready for the claim. Through an unspoken gentlemen’s agreement, and respect, they had long refrained from claiming each other’s motorcycles. Now each teams’ manager—Yamaha’s Kenny Clark, Kawasaki’s Steve Johnson, Suzuki’s Mark Blackwell and Honda’s Gunnar Lindstrom—were packing multiple cashier’s checks, and they plunked them down on the hood of the corner where the referee Butch Lee was handling the situation.

Within 20 seconds, nearly $40,000 worth of claims—11 in all—had been made on Tripes’ bike. Lee then went and got the first 11 starting chips that the riders drew out of a bucket before qualifying and put them in a sack, then he invited Roeder to draw first. The privateer reached in the sack and pulled out the #1 chip. Marty Tripes’ works RC250 was his. There was nothing anyone could do.

Honda’s Lindstrom even asked about the possibility of buying the bike back, and Roeder replied that he wanted $15,000 for it. The frustrated Lindstrom said that a decision would have to be made by the people at Honda.

When Cycle News asked Roeder what his plans for the bike were, he said, “I probably won’t race it. I ride a Maico now, and I don’t think I could set up the Honda to work as well. I’m getting ready to take it apart and measure it—porting—to see what makes it so fast. I may use some parts like the sandcast hubs on my own bike or sell the parts.”

When Lindstrom heard about Roeder’s plans to measure the porting, he told Cycle News, “He’ll have a good time doing it. He’ll find a production motor. The only difference is the centerport cylinder. We did lose a chassis, the double downtube. We’ll have to get Japan to make us another one. And the forks … we have all the valving and springs. Nothing he has will fit them. The main problem is that now Jon R. and Marty Tripes will have to spend a lot of long hours building and setting up a new bike. It’s more of an inconvenience for them than anything else.”

As for Roeder’s estimate of the bike being worth $100,000, Lindstrom replied, “He’s totally out in the blue. We’ll give him his check if he wants it, just to save Marty and Jon R’s time and work, but we’re not going to buy it back for any more than that.”

In the week that followed, lots of angry conversations between the AMA and the OEMs took place, including a face-to-face meeting at the LAX terminal restaurant. The next race would be the following Sunday at Saddleback, and there was genuine concern from the factories that others would follow Roeder’s lead and claim more bikes. They told both the AMA and Saddleback promoter Ted Moorewood that they would consider parking their trucks rather than racing their works bike at the risk of losing them.

“What I am paid to do does not include selling Yamaha works bikes at the track,” Yamaha’s Kenny Clark would be quoted as saying in Cycle. “The claiming rule is archaic; it stifles development. If you throw away all the research and development accomplished over the years, you would still be riding BSA Gold Stars.”

Added Suzuki’s Mark Blackwell: “I am under orders not to lose a works bike.” Blackwell added that he liked the claiming rule for amateur racing, but not for pros. “The rule is a nice idea, but it doesn’t work. Our bikes are actually near-future production versions.”

Kawasaki and Honda had similar concerns, leaving the AMA to make the difficult decision to suspend the claiming rule, immediately. The Saddleback National would go off that weekend with a starting gate full of factory riders in each class. Bob Hannah won, Marty Tripes finished second on a different RC250.

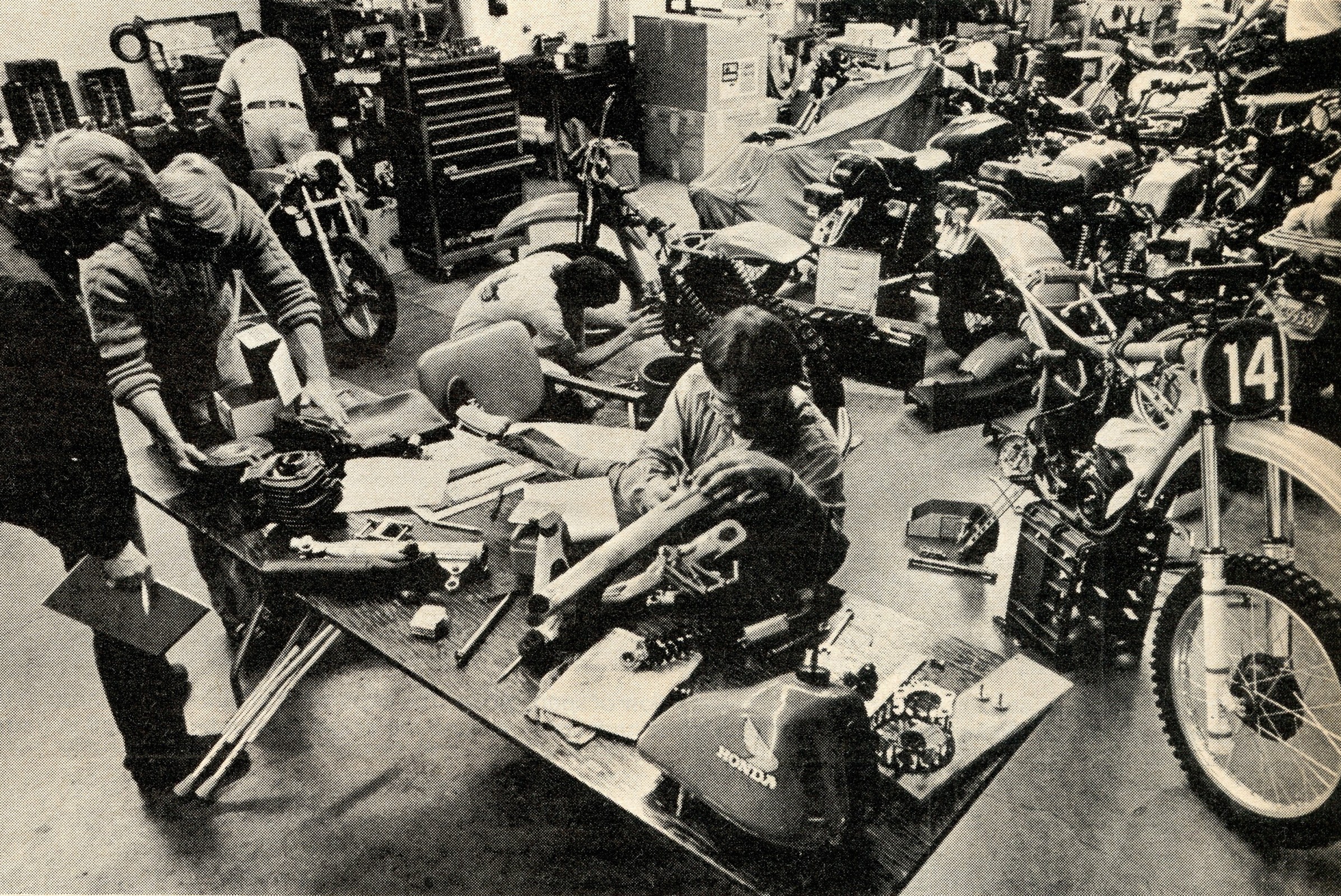

One rider who was not there was John Roeder. Despite having Tripes’ works bike, he resisted the temptation to race it and instead decided to prove his point by dissecting the bike, with help from Cycle magazine. When told by the magazine what was going to happen to Tripes’ bike, Gunnar Lindstrom answered, “We are thrilled to death that you want to do a story on the bike. Since we have already lost the machine, we can at least get some publicity out of it now. As far as we are concerned Roeder got a pig in a poke. Except for the centerport exhaust and the suspension the bike is stock.”

How “works” did the RC250 turn out to be, according to Cycle magazine? Not nearly as stock as Lindstrom implied, but not exactly a bike so out of this world that anyone could win on it, which is the same that could be said of any factory bike, then or now. The magazine feature summed it up this way: “Outside of the very special suspension components, titanium this and aluminum that; the bike was your ordinary factory racer. Which is to say there was very little stock about it at all.”

(If you want to read the entire technical dissection yourself, someone posted the pages on the Vital MX forum.)

Due to John Roeder’s successful claim of the bike Marty Tripes raced in the second moto at the 1979 Hangtown National, the claiming rule went away in AMA Motocross/Supercross. But pretty soon so did the whole concept of “works” bikes. Due to the rising costs of R&D and the level of performance that some had achieved, in 1985 the AMA decided to implement its controversial Production Rule for the 1986 season. That’s why you hear guys like Ron Lechien, David Bailey and Jeff Ward often say that their favorite bike was the one they raced in ’85—the last real works bikes in America.

Where is Marty Tripes’ works Honda now? After Roeder worked with Cycle on the story, he ended up putting it in storage for nearly three decades. Later, it would find its way into the hands of esteemed collector Terry Good of MX Works Bikes fame, and you can see it right here.

And if you want to know even more about this bike and some of the other most famous works bike ever raced, check out Terry Good’s book Legendary Motocross Bikes.

| Rider | Hometown | Bike | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  Bob Hannah Bob Hannah | Whittier, CA | Yamaha |

| 2 | | Santee, CA | Honda |

| 3 | | San Antonio, TX | Suzuki |

| 4 | | Norwalk, CA | Suzuki |

| 5 | | Rosemead, CA | Yamaha |

| 6 | | Montebello, CA | Honda |

| 7 |  Jim Weinert Jim Weinert | Middletown, NY | Kawasaki |

| 8 | | Tucson, AZ | Maico |

| 9 | | Yakima, WA | Yamaha |

| 10 | | San Clemente, CA | Suzuki |