This article originally ran in the May 2017 issue of Racer X Illustrated. Subscribe today for as low as $9.98.

If Jason Anderson were president, his approval ratings would make daily headlines. Over the last six months, he’s tracked wildly up and down, starting when he stuffed a broken foot into his Alpinestars and won the second moto at the Motocross of Nations in Italy, only to get landed on and taken out moments later by a Japanese rider he’d just lapped. That great high was countered by some lows this season after a series of rough-riding incidents. He’s been praised by some as a pit vigilante for taking out the paddock’s collective rage on Vince Friese. He’s also been criticized for being unable to take his own medicine. Anderson certainly dishes it out, including the very next weekend, when he crashed himself and Cooper Webb out of a heat race in Phoenix. A few hours later, he showed us his arm, bruised and swollen from the crash with Friese. He then casually mentioned the Webb crash, saying he got “whiskey throttle while going Mach 10” as he dug into a bag of potato chips. (Doesn’t that clash with his strict, Aldon Baker-designed training program?) Later, he sent out some Instagram posts making fun of Friese.

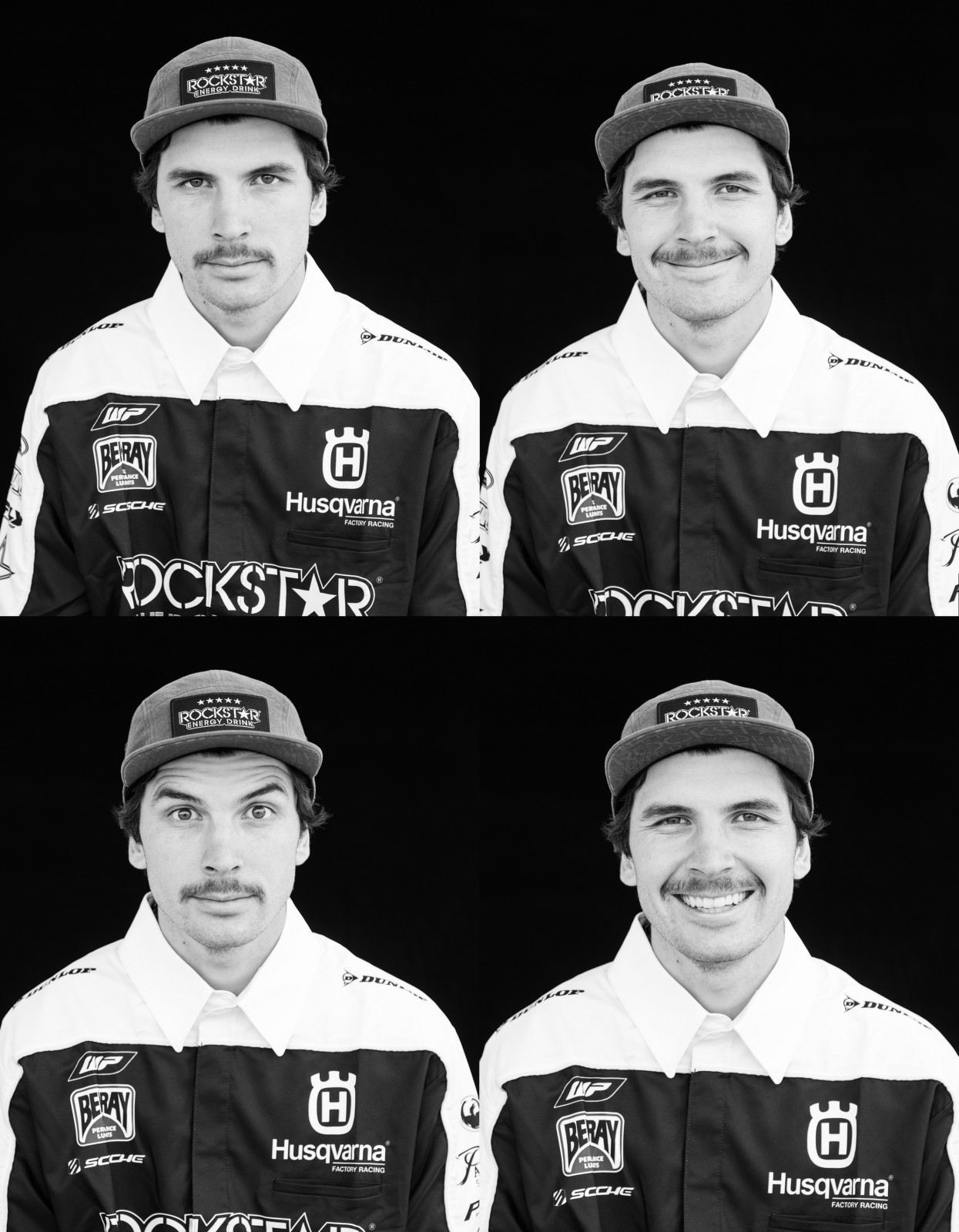

So what do you think of Anderson? Is he a gutsy, win-at-all-costs throwback? A serious trainer? A fun-loving kid? A punk?

Actually, forget what you think. Jason Anderson doesn’t care.

Keep It Simple

The Friese incident at Anaheim 2 represented the apex of the multiple Andersons. His previous rough-riding incidents never actually hurt his results—in fact, they probably helped. But when he and Friese collided in a heat race, Anderson rode up to the Smartop/MotoConcepts Honda rider (who is on lifetime probation due to a career of incidents of his own) and started yelling and pointing. Then he took a swing at Friese’s helmet, resulting in an instant disqualification.

(Friese calmly pulled a slick no-look grab of Anderson’s front brake while Anderson had his hand off the bar taking swings. “He got me good,” admits Anderson, who crashed right in front of the eight-year-olds staged for the KTM Junior Supercross Challenge. Children, hide your eyes!)

While Anderson didn’t take umbrage at the DQ—“As soon as I saw him,” Baker says, “he told me he went too far and knew he’d be done”—he didn’t express much regret. He never did the hostage tape-style apology, which Weston Peick did in a most un-heartfelt manner after punching Friese in the helmet multiple times last year. Peick still openly admits he doesn’t like Friese. Anderson isn’t any different.

“The team was bummed, for sure,” he says. “You don’t want to bring bad things to the Husqvarna brand. It’s a clean, blue-collar kind of brand, and that’s not good for them. They weren’t happy, and I wasn’t happy. Getting DQ’d isn’t good. But at the same time…look, I don’t like the guy.”

Did Anderson have any previous issues with Friese?

“I think everyone does,” he says.

For his part, Friese says he still likes Anderson and respects his speed and hang-it-out style. He even asked FIM referee John Gallagher not to DQ Anderson that night.

The next week, Anderson plowed into Webb in a sand turn in Phoenix, and both crashed. Webb spoke to Gallagher about it. Anderson chalked it up to aggressive racing.

See, Anderson might run it in deep, but he never gets deep in the analysis.

“I’m just a guy who likes to ride dirt bikes, and I just want to do good,” he says. “So that means I’m aggressive, and sometimes people are pumped on that, and sometimes people aren’t pumped on that. It’s pretty confusing from weekend to weekend, but you know what? I actually don’t give a shit. I’m paid to ride my dirt bike, and I have a good time doing that. I have a good time working with my team, too. That’s all I really care about."

Right to Work

Anderson crashed into Webb trying to take the final transfer spot on the last lap in the last turn. What’s the distinction between hard-nosed racing and straight-up dirty? No one knows, but Anderson isn’t asking for an answer anyway.

“I definitely feel like I’ve always gone for it, even through amateurs and all that,” he says. “You’re just trying your hardest to do good, and sometimes you make mistakes, but sometimes it works out and it’s pretty sweet.”

The Friese crash left him hurting, which really ramped up his emotion at the time. In fact, Baker isn’t sure if Anderson even would have been able to continue racing that night. He says Anderson really wanted to qualify out of the heat race and save energy.

Baker’s presence with Anderson always puzzles people. When Jason first joined Baker’s program in the 2014 off-season, many predicted he wouldn’t last a month. Three years later, there haven’t been any issues.

“All you have to do is ride the bicycle, ride the motorcycle, and do the gym stuff—it’s not that bad,” Anderson says. “But I guess people perceive me as a guy who likes to have a good time. I obviously don’t fit the mold of how this type of training usually is. But I have no problems with it, and I see myself staying there and doing it my whole career. I mean, for sure, there are times when you’re tired during the season and you don’t want to go on a road ride. But I don’t ever feel like I’m ever burnt out. I still love to ride my dirt bike.”

Dark Days

At one point, Anderson wasn’t sure if he would be able to race a dirt bike for a living anymore. His rookie pro season in 2011 was a disaster—so bad that Rockstar Energy Racing team owner Bobby Hewitt and former team manager Dave Gowland benched him at midseason and told him to get in shape. Hewitt has proven fiercely loyal to his riders, and, seven years later, that relationship has paid off.

Anderson admits he doesn’t love to train. He also says he doesn’t love doing interviews, or really any of the things that go along with being a professional athlete. Fan stuff? Autographs? Being famous? He would rather just stay in the shadows and ride his dirt bike.

“For a minute there, I got sidelined by [Rockstar] Suzuki,” Anderson says of his tough rookie year. “I was like, ‘Oh, shit, I’m either gonna be racing in Canada or I’m going to have to quit and go to school.’ You see the money you can make, and you know you can have a job riding a dirt bike, or you can have to get a regular job.”

Putting in work is one thing, but how does Anderson just casually roll with the Baker program—arguably the toughest in the sport? I ask if, perhaps, the program isn’t as strict as it seems.

“Yeah….” he says while trying to find even a single example of the program allowing him to get loose. “Yeah, we’re pretty strict."

“He doesn’t adjust things for anyone,” he says of Baker, followed by a long pause while he contemplates giving up some secrets. Then Anderson starts laughing before finally copping to his real excuse. “I can have a good time, but basically, you don’t have to tell Aldon everything!

“I feel like if you have respect toward him and respect the program, he understands you’re human and you’re going to want to go out and have fun sometimes,” he says. “Not everyone can just sit in their house and think about dirt bikes all the time. I have a good crew of buddies, and we hang out.”

Those buddies, Baker, and his team are the only people Anderson tries to get approval from. Anyone else? Nah.

El Hombre Don’t Care

When riders get heat from fans, they often try to use the press or social media to tell their side of the story. Not Anderson. He even downplayed his Motocross of Nations star turn—remember, he doesn’t like doing interviews anyway. Why doesn’t he tell anyone what he thinks?

“Because most of the time, I don’t care!” he laughs. “Actually, sometimes I’ll post something on Instagram just to fire people up. Just spice it up a little, then maybe I’ll take it down. I like stirring it up like that sometimes. What are dudes going to say? Dudes that ride at local tracks are going to tell me I suck? Why would I get that mad? My life is pretty good because I get to ride dirt bikes for a living.”

He’s a free spirit, except when it comes to one very serious subject: spending his money. Says Anderson flatly, “I don’t buy anything.”

Anderson’s mother and grandmother were teachers. His family tree features four generations of railroad workers. He does not take his good fortune for granted.

“I don’t even have furniture at my house in Florida,” he says. “I have a couch and a bed. I’m not going to live in Florida when I’m done racing, so I’m not going to blow my money on furniture just to have to sell it.”

Blow all of his money? Anderson can certainly afford an Ikea run. Apparently, he would rather stash people than furniture. Here’s his real estate 101:

“I own two houses in California. I had three houses for about a minute, but I sold one. My one other house, I rent it to some guys on the team. The house that I live in in California, it has five bedrooms, and every one of them is rented out. And Zach Osborne’s practice mechanic lives in my house in Florida. So I’m never living alone, and I’m always pulling some rent in.” Additionally, in California, he uses a pickup truck he got for free from a dealership.

Anderson is 24 years old. He’s already run the numbers and says he could retire now and live comfortably forever. (Don’t worry, he plans on racing for a while.) So maybe that’s it? Maybe the wild child settles because he wants to make more money?

“I don’t want to do it for the money,” he says. “That’s not why I’m here. But sometimes it helps. Sometimes when it’s tough…. I’ll tell you this: If I wasn’t working hard and I was killing it, I probably wouldn’t bother working hard.”

At this level, it’s too tough to succeed without hard work. As a result, there goes Jason Anderson each day, toiling even though he might not want to, being famous even though he doesn’t want to be, but doing whatever he wants to on the track. Someday, he’ll get to be himself—whoever that is—every day. Will he keep training then, just for fun?

“Hell no,” he says. “The day I retire, I’m selling my road bike.”