This sport celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. On March 29, 1924, an off-road race was held on Camberley Heath in England, called the Southern Scott Scramble. Motorcycling had become very popular in the years before and after the First World War, and during the war motorcycle messengers became critically important on both sides of the Western Front. Motorcycle competitions were just getting started when the war broke out, including the Scott Trial in the spring of 1914, named after a man named Angus Scott, who built and sold motorcycles. The war started later that summer, and such events were put on hold.

After the war ended in 1918, motorcycle competitions of skill and agility (trials) became popular in both England and France. Sections of each trials event were "observed," meaning there was a time element and limits on some sections, as well as penalties in some sections for a rider touching the ground with his feet to stay upright. However, organizers of what started out to be the Southern Scott Trials decided that the one held on Camberley Heath would be scored strictly on speed. In other words, the first rider to cross the finish line after two laps around the long course was declared the winner. And because the event would not have observed sections, the ACU sanctioning body for British motorcycling ruled that it could not be called a trials event. So, they called the race around Camberley Heath a "scramble" instead, a term that the French would soon change to moto cross. And just like that, our particular form of motorcycle sport was born. Races like the infamous Isle of Man TT were already popular before the war, but off-road events? Not so much. The first winner?

Years ago Bryan Stealey, the original managing editor for Racer X Illustrated, decided to dig a little deeper into the history of this first motocross event, which would be won by a man named A.B. Sparks on a Scott motorcycle. He flew to London and then hitched a ride out to Camberley and went digging into the archives of the local library, newspapers, history books, and more. He then wrote the definitive history of that first race—the Southern Scott Scramble—for the magazine. Before the year of 2024 ends, we wanted to share Bryan Stealey's epic feature "A Rare Old Scramble at Camberley Heath" right here:

A Rare Old Scramble at Camberley Heath

The answer to one question about the history of motocross has long escaped students of the sport: When was the first race? British motocross legend Jeff Smith once said that the details of this monumental event had been "lost in the mist of time." According to renowned French moto journalist Xavier Audouard, the FIM (Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme) doesn't even know where or when motocross started. There have been numerous hypotheses about the origins of the sport: that it was started in the wastelands of Western Europe by unemployed soldiers after World War I; that men testing new British motorcycles began racing one another on closed off-road courses behind their factory north of London; that French postal workers on motorcycles challenged each other to match races after work; that 1920s-era flat track and soon-to-be-outlawed board-track races in America took to the countryside.

What we do know is that the first FIM-sanctioned world championship of motocross took place in 1947. We also know that the name "moto cross" originated in France. But the very birth of the sport—the first race—was never fully determined.

Upon looking into the history of motocross, we discovered a curious passage in a series of old motorcycle publications about an off-road race, with no observed trials sections, that took place outside of London in the early 1920s. Because it was the first of its kind, modern-day reports on the event were few, and many of them contained conflicting information. So the search was on to find out more about this first meeting from surviving family members of the participants, local libraries and club historians, even a journey to England – and to the very land on which the race was held – to search for clues.

Finally, after months of research, the mystery of where and how our sport began was finally solved. Motocross, as it would later come to be known, began as "a rare old scramble at Camberley Heath" in England on the 29th of March, 1924.

Motorcycle enthusiasts were riding off-road for years before the Southern Scott Scramble in '24. At first, it had nothing to do with racing; riders gathered to test their prowess in primary races – the fastest and riders had to get from point A to point B by any means necessary. Eventually, more experienced riders developed a propensity for "rough riding," and clubs started to hold the first trials events.

In the spring of 1914, the now-famous Scott Trial was born, thanks to the ingenuity of Alfred Angus Scott, owner and founder of the Scott Engineering Company. Originally a kind of company outing for the employees of the Scott motorcycle manufacturer, the Scott Trial was organized on the open Yorkshire moors in Northern England and was comprised of bogs, rocks, and stream crossing. There was a time element in the competition, but there were no observed sections as well. The winner was simply the person finishing the event in the fastest time. (At the time, Scott motorcycles were much better known for their success in TT racing at the Isle of Man.)

By 1923, sales in Britain were on the rise again. Thousands of people had motorcycles, and membership levels in clubs were at an all-time high. Enthusiasts of the day were looking for fresh and exciting ways to compete with their newly-acquired steeds. One club in southern England – in Camberley, more specifically – had a big idea on the verge of fruition.

By the early '20s, the Scott Trial had achieved widespread infamy. The most skillful trials riders in Northern England gathered in the autumn to pit themselves and their machines against the brutal conditions of the moors. Club members from the North tested their riders on rough terrain, where their riders were just as good (or better); their terrain just as tough (or tougher).

According to legend, Ilkley Club member G.G. Kitson boasted to E.O. Spence, the honorary secretary of the Camberley club, that the northerners could smoke the south on the rough stuff. "You haven't a tithe of the tough spots we possess in Yorkshire," challenged Kitson. The Ilkley Club agreed to send some of its best members to compete in the south on the condition that Camberley "laid down a course with a time limit," something forbidden in the Scott Trial. Then as now, Spence and motor trials ran strong for the "Southern Scott Trial." This event still holds an important place in the hearts of many older racers, who would be observed at later meetings. The only rule was that the major test would be a long cross-country run.

The Motor Cycle magazine reported the results of the Scott Trial:

"Camberley has overcome the bugbear of the average trial in a masterly way. At most of our meetings, no observers attend, and it is left to a few poor old hard-faced launchers to compose what may – when they please – form a 'judgment.' Of course, the riders had to run over 40 to 50 miles of bog, hill, and rugged terrain, and this test was perhaps the first time anyone realized the distinction that marked the event."

The Southern Scott Scramble was to be held in the vicinity of Camberley Heath and Bagshot Heath, located in the sleepy London "suburb" of Camberley. The heath was mainly uncultivated land ordinarily used for cavalry exercises and tank drills. A considerable buzz circulated throughout the area, and come race day—Saturday, March 29, 1924—a crowd that reportedly numbered in the thousands showed up to watch this strange new competition.

Competitors arrived early in the morning aboard the very machines on which they would compete (after removing their more breakable parts, like headlights). They registered and paid their entry fees, which were to go to St. Dunstan’s Hostel for the Blind. General betting among the riders was that riders by way of George Dance, a British motorcycling icon, might win (this was for reasons listed in the next section). Dance, who held numerous speed trial records, was also considered to have a heavy favorite in Camberley.

There was also talk about the extrovert Gus Kuhn, a Velocette rider who was very familiar with the Camberley Heath. The previous year he had won a Camberley club-promoted speed hill climb there aboard a single with a tireless, studded rear wheel. On this day, he would stick with the singles.

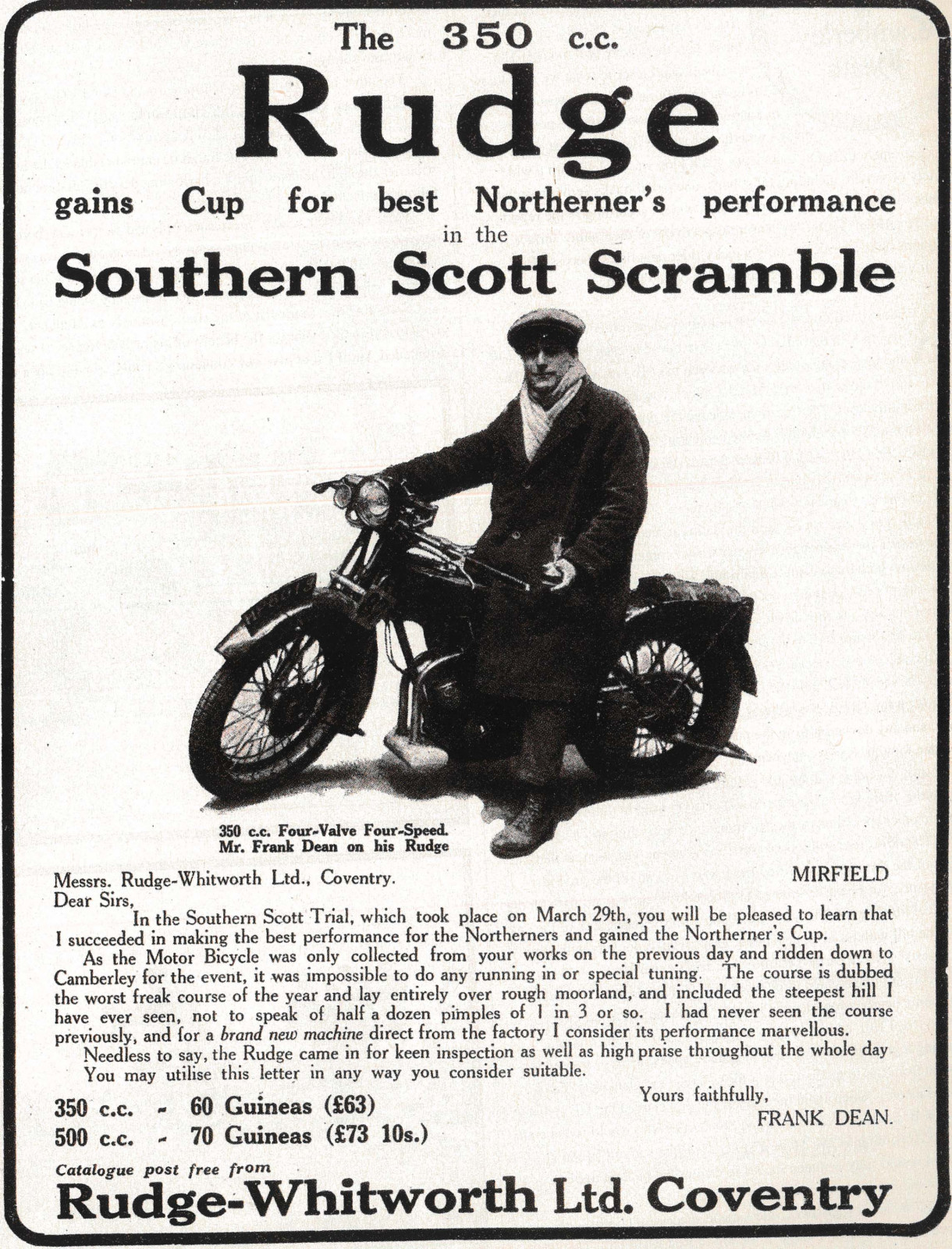

Then there was Frank Dean, the fastest northern team member of all the entrants. Dean must be considered the first full-factor rider if ever there was one. The day before the race, he picked up a brand-new 539cc Four-Valve Four-Speed entrant from the Rudge factory. In those days, breaking in a motorcycle was extremely important, so many felt the race would cause some problems for the popular rider.

In the morning, the riders would break at nearby Frimley for an extended lunch, and then line up for a second 25-mile lap. (Even in those days there were two motos!) The trail itself was closer to what we now know as cross country racing than it was to modern motocross. It was marked with red powder, arrows, and the occasional flag, though at times it was extremely difficult to navigate. Each loop was replete with a wide variety of terrain, including hills, bogs, uncharted tracks across moorland heather and ditches, and water splashes, which, according to the report from The Motor Cycle, "for reasons respectively of either surface, glutinous nature, or depth, only a lucky rider negotiated successfully." It was going to be a long day on Camberley Heath.

Riders lined up for their start in their predetermined order. There were two courses—one in the northern hemisphere and one in the southern. The fastest aggregate time between the two laps would win. The course started out with a brief straight, which immediately led into a step-by-step ascent. It was described this way in The Motor Cycle: "The hill at 300 yards long and extremely steep, so naturally it was the first point of interest to which the spectators flocked."

At Wild and Woolly, a rope had to be used to pull riders up the final portion of the hill with a narrower stretch and crumbling rocks that made it even more difficult for those not cleared for the climb. Spectators cheered and dragged competitors forward, with the event quickly becoming a major talking point for the day.

At the top, Wild and Woolly was the most treacherous hill on the course, but getting down again was a much more complicated business, calling for close concentration on the trail ahead.

The bikes of the day—Scott, Sunbeam, Rudge, Henderson, A.J.S., Triumph, Norton, Harley-Davidson, Zenith, A.B.C., Montgomery, Bradshaw, and Velocette among them—were typically equipped with two or three gears. Seventy-five percent of the course demanded middle or low gear, with the remaining 25 percent—dirt trails through woods and across moors—allowing the riders to switch into high gear. Some of the long stretches mentioned in the plans allowed participants to reach impressive speeds of up to 50 miles per hour, which, with little suspension and virtually no safety equipment, was a major feat!

As if the course weren't difficult enough, one incident during the morning loop proved to be critical to the results of many. It seems that the day prior to the race, the race markers had been removed, causing some of the riders to lose their way. Among the victims was George Dance, who finished behind the leading group after wandering off course for some time before finding his way back.

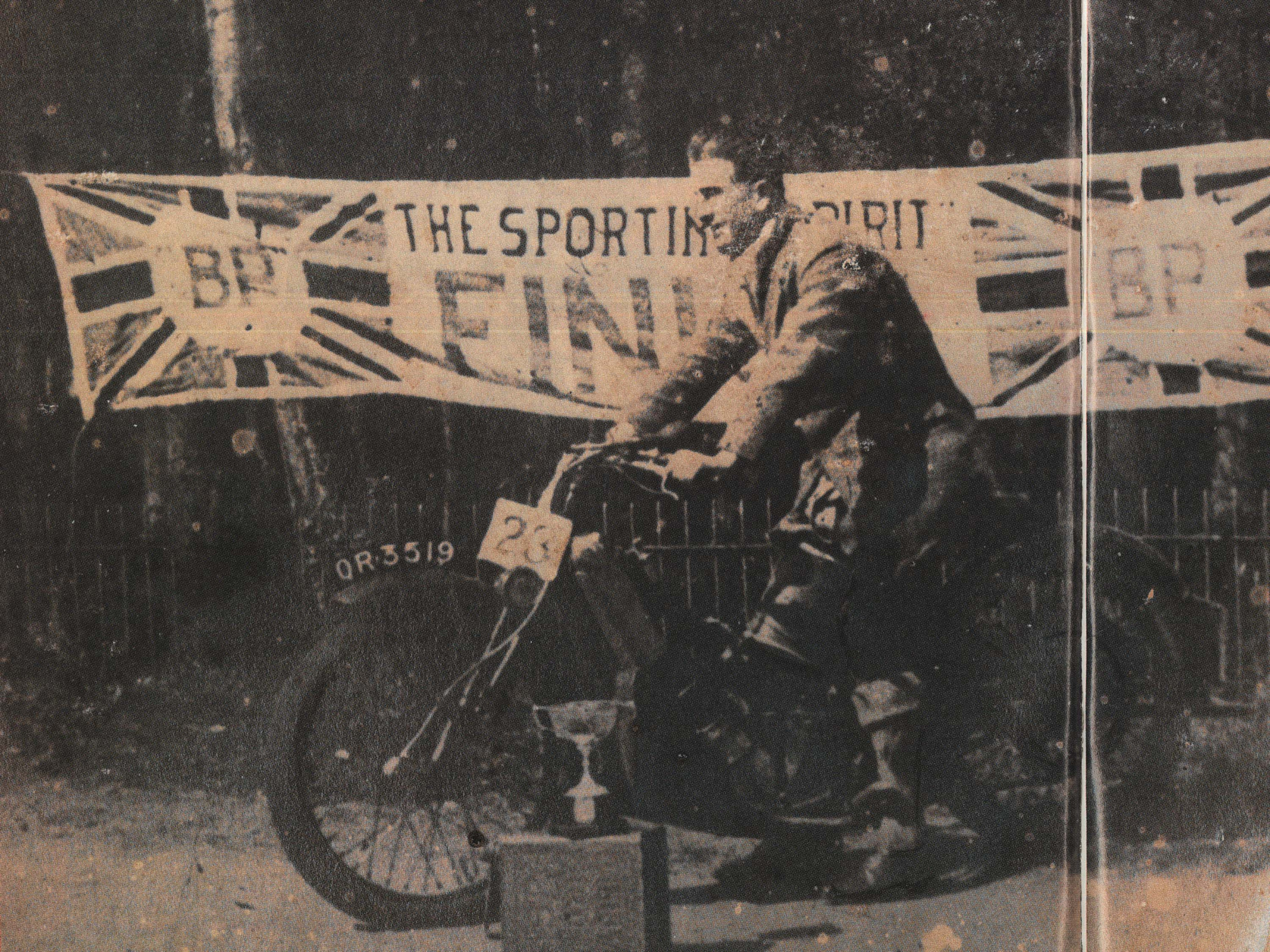

In the end, 40 of the 80 starters would finish the Southern Scott Scramble. The winner was local man Arthur Sparks, whose knowledge of the heath allowed him to avoid the misdirected route caused by the earlier marker removal and complete the 50 miles unfailingly.

"With wheels spin, in a time more like 100 minutes," he would joke later. His aggregate finish time was two hours, one minute, and 15 seconds—almost nine minutes ahead of second-place George Dance—and his average speed was nearly 25 mph. The premier award, the Burnett Cup, went to the event's organizer and guest rider from Yorkshire, Mr. Spence, while Sparks had just secured his first trophy of glory.

George Dance took home the prize for Best Southerner (besides Sparks, of course), and Rudge rider Frank Dean was declared the best Northern rider, having just missed the podium. His finish was one of the day's biggest surprises (109). The Northern star’s original event experience was crucial, but Spence offered commentary on the event's origins and noted that the added tracktime this year was truly helpful, both in the north and south.

"Without a doubt," he said, "and indeed the steepest hill (Wild and Woolly) I have ever ridden, and I kept spinning my way up it with the very best tires and methods in my experience."

Although the top two finishes were turned in by southerners, the 12 northerners who made the trip had a better average time. Nobody conceded, and the debate over which region produced the best riders raged on. The event was considered a major success by competitors, spectators, and journalists alike.

Scrambling was quickly recognized as the next big thing on both sides of the English Channel. The French seized the new form of motorcycle racing and gave it a slight makeover, shortening it and adding laps and a few man-made obstacles like jumps. They also changed the name from "moto-cross"—a combination of "motorcycle" and "cross-country."

Throughout the following years, scrambling would evolve in England, and riders would be drawn to the sport in droves. English trials, like the Southern Scott Scramble, continued in a couple of larger loops over shorter periods, and it eventually became a feature of almost every competition. In fact, by 1947, the FIM was ready to name a proper world champion. The first-ever FIM-sanctioned motocross world championship was held in Wassenaar, Holland. It drew 55 riders and a few dozen top names from Britain, France, and Belgium.

The history of the first race is still up for debate, but we can trace it back to this March day in 1924 at Camberley Heath. Although British riders won the day, they took part in perhaps the most grueling off-road race to date. Some participants say the true history of motocross started with trials on British moorlands, while others believe this was the real birth. One thing is certain: Arthur Sparks played a major part in it all.

Is there more to it? Certainly. There's still more to the story, but history has been unclear. Or perhaps it simply has been lost in the mist of time.

The Southern Scott Scramble

Camberley, England, March 29, 1924

Top 10 Results

- A.B. Sparks (Scott)

- George Dance (Sunbeam)

- Frank Dean (Rudge)

- H. Langman (Scott)

- F.J.R. Heath (Henderson)

- R.B. Budd (A.J.S.)

- A.E. Leeding (A.J.S.)

- B. Johnson (Norton)

- P.L.B. Wills (Harley-Davidson)

- W. Clough (Scott)

Official Awards

- Premier Award: Burnett Cup and Castrol Prize: Arthur Sparks

- Cup for best Northerner's performance: Frank Dean

- Cup for best Southerner's performance: George Dance

- Cup for best 250-600cc performance: R.B. Budd

- Cup for best American machine performance: F.J.R. Heath

- Team Prize: Willington M.C.C.

- Trade Team Prize: Scott team

Sources

Carrick, P. (1969). Motor Cycle Racing. The Hamlyn Publishing Group.

Carroll, J. (2001). The Complete British Motorcycle: The Classics from 1907 to the Present. MBI Publishing.

Collins, P. (1998). British Motorcycles Since 1900. Ian Allen Publishing.

Clow, J. (1974). The Scott Motorcycle. The Haynes Publishing Group.

The Motor Cycle (magazine), March 6th, 1924.

The Motor Cycle, March 27th, 1924.

The Motor Cycle, April 3rd, 1924.

The Motor Cycle, April 10th, 1924.

The Motor Cycle, April 17th, 1924.

The Motor Cycle (magazine), April 2, 1924.

Personal interview with Dave Hull (friend of Arthur Sparks), April 17, 2001.

Personal interview with John Sparks (son of Arthur Sparks), April 17, 2001.

Personal interview with Ralph Venables, August 12, 2001.

Reynolds, I. (1977). Racing Motorcycles. Rand McNally.

Trials and Motocross News, May 1994.

Surrey Advertiser (newspaper), April 5, 1924.

Walker, M. (1960). Book of Motor Cycle Racing. Stanley Paul and Co., Ltd.

Wilson, Hugo. (1995). The Encyclopedia of the Motorcycle. D.K. Publishing, Inc.

I'd like to thank the following people and organizations for their help with this project: Matt Allard, Duncan Smith and Ray Kennard for putting me up and joining in on the hunt; Mark Mederski and the Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum; Annice Collett and the Vintage Motor Cycle Club; Stan Lawless, Alison Galloway, and Duncan Spokes for pointing me in the right direction; Ralph Venables; Justine Pearson and Mary Bennett of the Surrey County Council; Mary Bennett and the Surrey Heath Museum; Craig, John, and Muttley of The Dog Pub for the Guinness Extra Cold; Jane Skayman of Mortons Motorcycle Media for help with photos; Whitehorse Press for having an excellent selection of motorcycle books; National Rentals for upgrading me to a Mercedes for free; Johnny Arrows for not beating up me and Allard; John Sparks for being on the receiving end of crucial comments about his father; and finally Dave Hull, who passed away the day after I spoke with him in Camberley. Godspeed, Mr. Hull.