By Tom Mueller

It’s a great day to be at the races.

I made the three-hour drive from central Wisconsin to Millville, a small community (population 182) nestled along the Zumbro River in southeast Minnesota. On this day, the body count swells as thousands converge on Spring Creek Motocross Park for the Lucas Oil Pro Motocross Championship. I stroll through the pits as an unknown—call me the motocross ghost of seasons past. I cast a shadow across the sport as a Cycle News East reporter, then a Wrangler promotions rep, and later as director of pro racing for the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA).

And now, I am only a vapor.

But that is as it should be. Generations progress, new leadership emerges. What is past cannot govern the future. There’s a valid statement: “You can’t know where you’re going… unless you know where you’ve been.” That surely rings true for motocross. Now I have an opportunity to reflect on an epic event at Millville that was “where you’ve been” related to our modern sport status, which indicates “where we’re going”—the past, the present, and what we learned along the way. For this article, recollections of the very first national motocross event at Millville in 1983, related to the most recent in 2018.

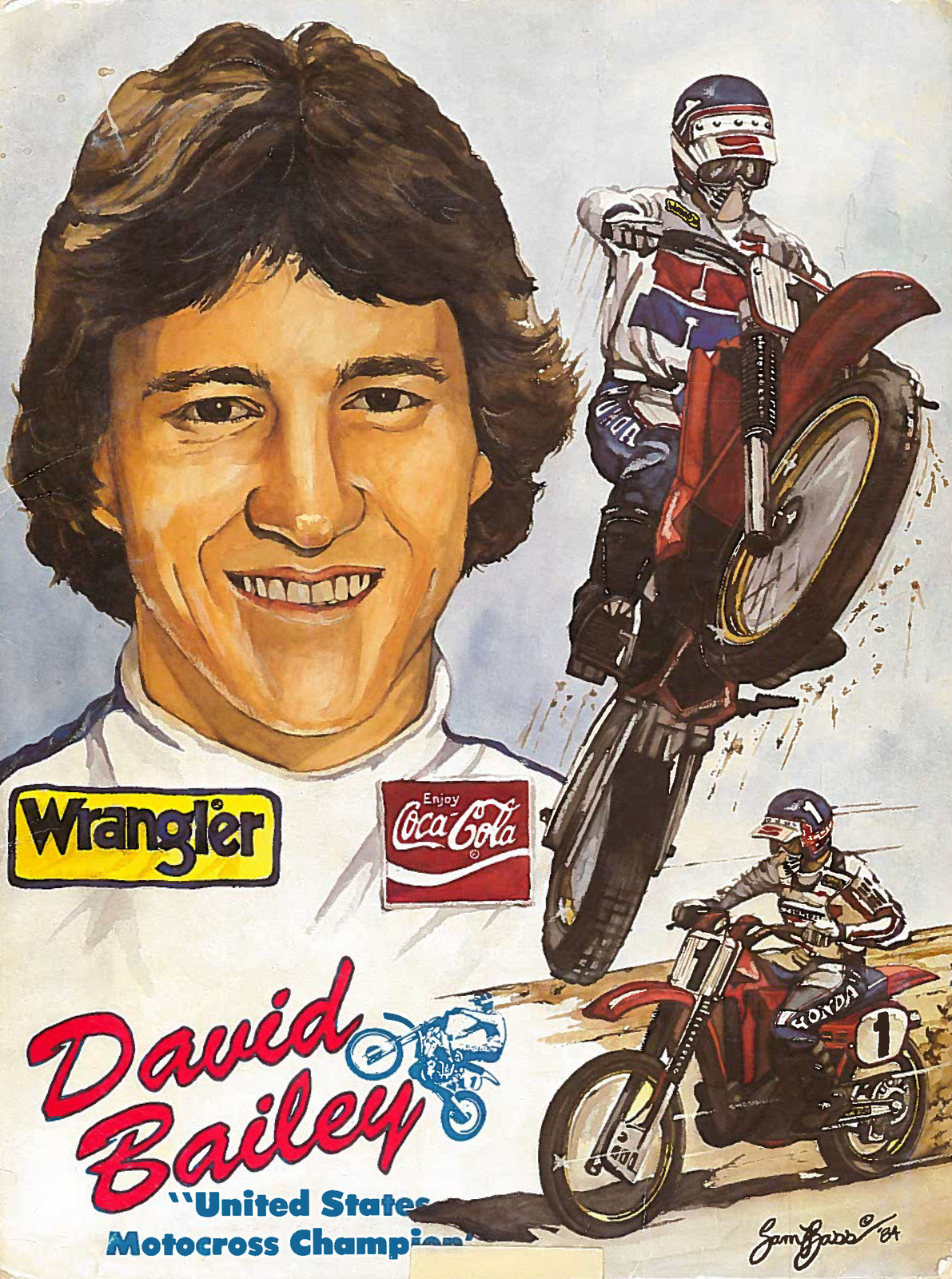

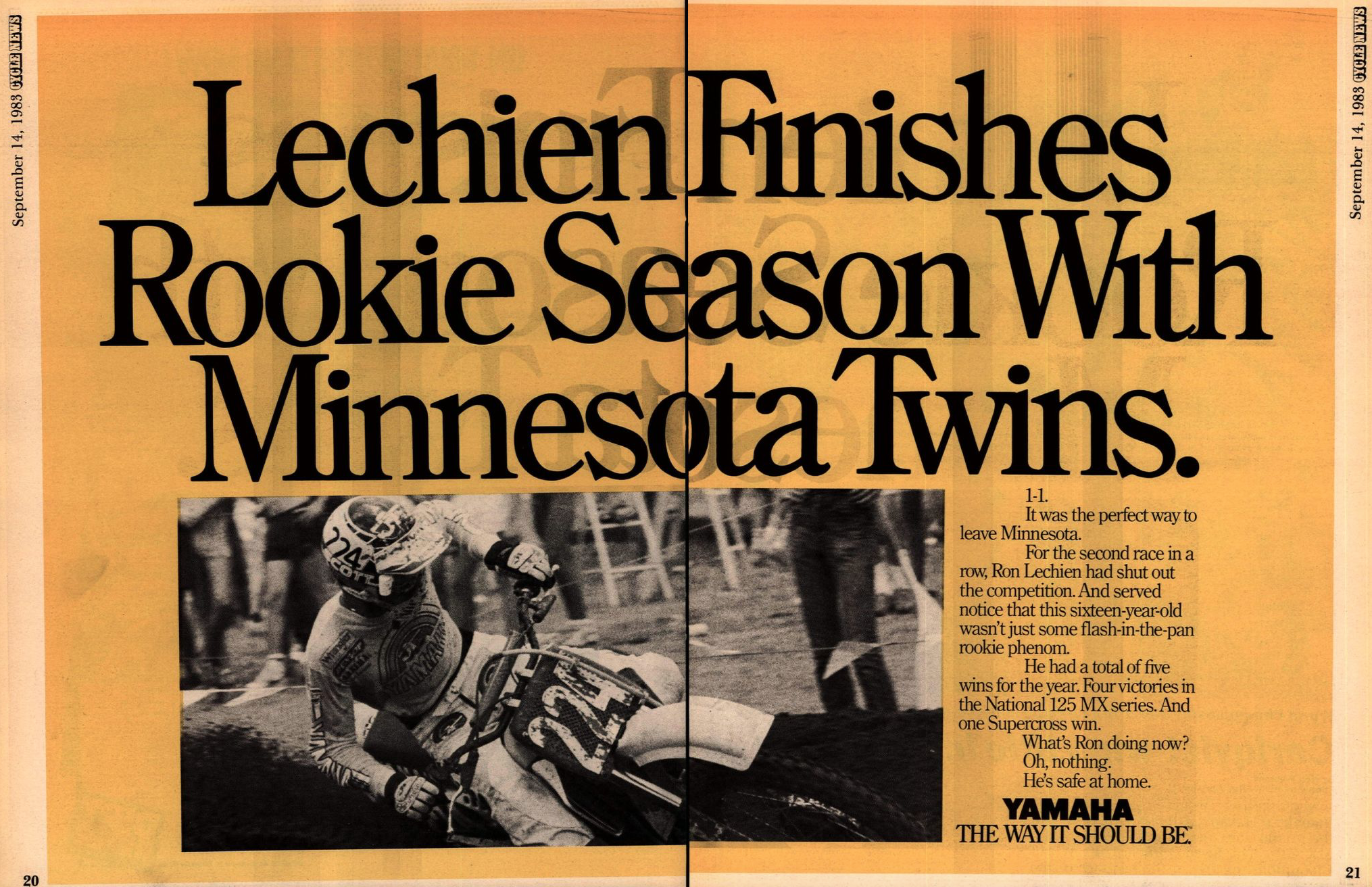

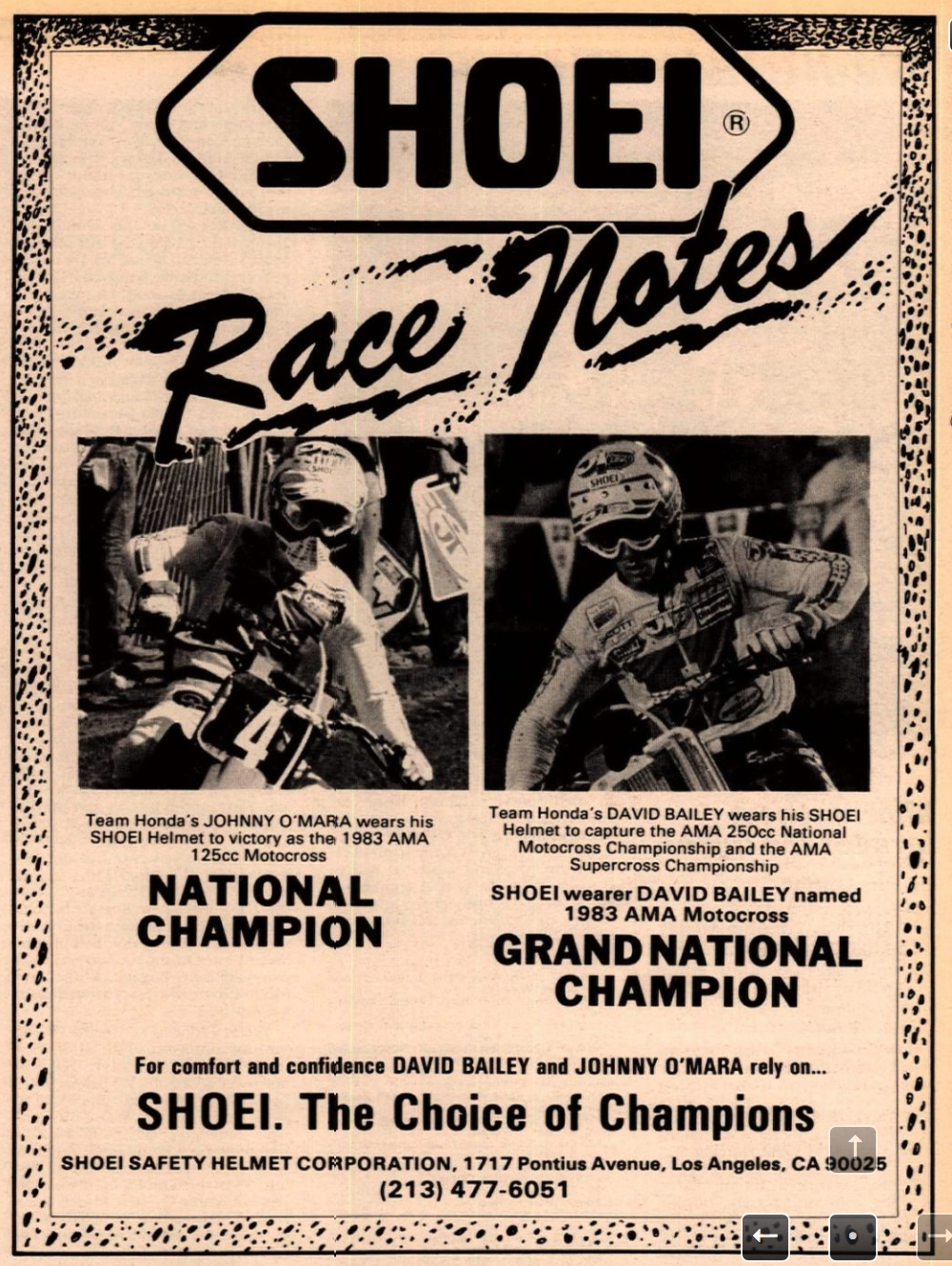

The inaugural event at Spring Creek Motocross Park constituted round 27 of the AMA/Wrangler Super Series. Several notable things occurred at that event. Teenage sensation Ronnie Lechien took his rotary valve works Yamaha to a 1-1 overall win in the 125 Class—his third national win of the year. Johnny O’Mara couldn’t feel his foot but protected a nine-point lead to take that year’s 125 AMA National Championship. Bob Hannah was back, fighting injuries but taking his factory Honda to 1-2 for the 250 overall; his Honda teammate David Bailey went 4-1 for second on the day, enough to own the 250 National Championship. Danny Chandler took his support-program Honda to a 1-2 for overall, besting Broc Glover’s 3-1 in the 500 Class. But it was Glover’s day, as he was crowned the 500 National Champion.

Bailey also amassed the highest total of supercross and outdoor national points to claim the Wrangler Super Series Grand National Championship. The Wrangler Super Series was never widely supported by the factories; the concept of combining points across the three national championships and supercross did not gain (metaphorical) traction. To better explain this, consider the political structure of motocross in the eighties. Racing was governed by the AMA, which parsed out contracts to hold events, called sanctioning agreements. A sanctioning agreement was held between the AMA and each independent promoter. This resulted in pseudo-collaboration, a loose association between the AMA and its chosen motocross event partners.

Here’s the rub: Wrangler held its contractual relationship with the AMA. The apparel manufacturer was building its brand in the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) and in professional rodeo through the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA). Wrangler noted the marketing focus on a singular champion in NASCAR and wanted to model a program in motorcycles, similar to the NASCAR Winston Cup Series.

When you want to get things done in auto racing, go to NASCAR. When you want to make it happen in motorcycles… get in bed with the AMA?

The championship paid out $30,000 to the winning rider; however, most other promotional funds were directed to the AMA. The Wrangler series came to the promoters through language in its sanction agreement. Factory representatives were aware of Wrangler’s intentions through their roles on the AMA board of directors.

The manufacturers wanted national championships. They paid riders major dollars to win it. While still at Cycle News, I was interviewing Darrell Shultz, who disclosed Honda would pay a $100,000 bonus for the AMA Supercross Championship. Assuming factory bonuses were similar across factories and classes, thirty grand from Wrangler posed a weak comparison. However, what made the Wrangler Championship interesting in 1983 was that the points race was playing across national classes. That was common among grand national road racing and flat track racing, but never in motocross. So, it was one and done. The Wrangler Super Series was awarded in 1983, and not soon after, the corporation was developing its strategy to divest itself of motorcycle sport.

My memory is fleeting. Now in my early sixties, I have a great hard drive—the data exists—but my short-term RAM memory doesn’t always provide the fastest recall. When I’m in doubt for motocross facts, I turn to an individual who happened to be at the ’83 race, one who holds an amazing ability to put most any race in playback mode.

“I had Peter Starr [Honda documentarian] in my rental car getting thoughts on the way to the track,” Bailey recalled. “I had barely squeezed out the SX title at the Rose Bowl over [Mark] Barnett. The Wrangler Grand National title was still a possibility; wrapping up the outdoor 250cc title seemed certain barring disaster. I told Peter I was going to treat it like any other race. I would probably wrap up the 250 title after the first moto and the Wrangler GNC would be a bonus. I didn’t have a worry in the world. Just to go out there and go fast!”

That’s not how it worked out for Bailey.

“I grabbed the holeshot and planned to run away. I thought I might expect a challenge from Hannah. As we entered a nasty whoop section, Scott Burnworth blew past me, then Hannah, then [Rick] Johnson. I felt heavy and tight and slow. I wanted to regroup and keep my GNC title hopes alive, but the best I could do was even pace those guys, gaining no ground.

“I felt the Wrangler blue #1 plate slipping away, but to keep myself in a positive frame of mind, I focused on winning the 250cc championship. Hannah ran away with the moto, followed by Johnson and Burnworth. I finished a distant fourth. I was the new 250 National Champion but disappointed in my riding, perhaps losing the Wrangler GNC title by only a couple points.”

A major championship had yet to be settled, and it would come down to two different riders in two separate national classes. There was plenty of pit chatter between motos. The factories may not have initially been focused on the Wrangler GNC, but it was surely discussed as part of race tactics. Reminiscent of the “Let Brock Bye” Yamaha team tactics in 1977, was Bob Hannah once again solicited to let his teammate make the pass, this time by Honda personnel? The consequences of winning over second place created a scenario where three valuable national points were at stake (a national win pays 25 points, second pays 22 points, third pays 20).

“All the focus shifted to me and Mark Barnett,” Bailey said. “I had to win [in the 250 Class] and Barnett had to lose [in the 125 Class]. I pulled the holeshot and was riding with nothing to lose and a lot to gain. I was mad about my first moto; it was perhaps the best I had ridden all year. I gapped the field, then I started getting glimpses of Hannah closing that gap. I was soon engulfed by ‘The Hurricane’ and I couldn’t hold him off. I wanted to win and wanted to beat him fair and square, but he was just too fast.”

The track layout at Millville for the 1983 event was quite disparate from the 2018 design. In ’83, the track threaded in and out of woods sections, lending an endure effect to the sandy, whoop-infested layout. “Near the end of the moto, I closed the gap with one last push and Bob was apparently laying up. At the top of the hill, out of view of everyone but a flagger, Bob went wide and I went by. I was torn, but I knew I had to receive that gift and ride my guts out purely to show Bob the size of my heart, the amount of my appreciation, and respect for myself.

“With one lap to go, Bob was all over me! Was he going to pass me back? I came into the final two corners with Bob showing me a wheel. In the final left-hand turn I went in hot, made the berm, and grabbed the checkered flag as Bob high-sided and crashed. I gave it 100 percent and Bob did it right. He made clear he didn’t just roll over and obviously let me have it.”

Hannah won the day and Bailey’s 4-1 kept him in queue for the Wrangler Grand National title—unless Barnett won his final 125 moto. Mark lost the supercross title by two points (to Bailey). He lost the 125 title to O’Mara in the first moto at Millville. One redemptive moto remained, and Barnett needed to perform in stifling heat and humidity if he planned to close the deal and salvage what was left of 1983.

Lechien jumped to the early lead and held it to the halfway point, but Barnett was closing. There was a massive crowd on hand, and for that moment, the premise of the Wrangler Series was in play. Bailey wasn’t on the track, but fans knew what was at stake. It went all the way to the final turn. Barnett closed to Lechien’s rear wheel and applied pressure. Going into the final corner, Barnett tried to wedge his way by, but Lechien held on. The upstart teen swept the day and the final four motos of the series.

O’Mara rode to a fifth-place finish, but wasn’t part of the after-race celebrations. “I broke my toe at the Rose Bowl Supercross,” O’Mara recalled, who was at the 2018 Millville event working out of the Monster Energy/Pro Circuit Kawasaki compound as a mentor to Joey Savatgy. “I had a doctor at Millville who was shooting me up (with deadening agent). I couldn’t feel my foot, and my goal was to stay out of the way.” Bailey reported Johnny’s foot was creating excruciating pain. Coupled with the pressure of finally winning against Ward and the seemingly unbeatable Mark Barnett, he ended his evening in his hotel room… with a puke bucket.

“It was a great day for me, but at the same time, I really felt for Mark. His bike let him down a couple of times that year and that would’ve changed everything,” Bailey said. In the Cycle News report on the event, Barnett stated, “I was just the victim of team racing by Honda, no doubt about it.”

If you want to see the aforementioned Peter Starr’s film on the way the 1983 season played out, check it out right here:

It even includes the pre-race conversation Bailey had with Starr as he drove to the track, starting just after the 21-minute mark.

So that’s how it was in 1983; what’s different about 2018? Two national classes ran on the day, rather than three. The psychological penny dropped for 250 Class rider Aaron Plessinger, who put his erratic ways aside and went 1-1 on his Monster Energy/Yamalube/Star Racing Yamaha. Monster Energy Kawasaki’s Eli Tomac had to work for it, getting ahead of Ken Roczen and Marvin Musquin, to go 1-1. In that regard, racing stays the same. There are a bunch of fast riders at every national, but a handful are a cut above in their given era, untouchable by the field. But subtle differentiation exists. Please follow along on my then-to-now assessment.

Fitness and nutrition

In ’83, riders were experimenting and finding out what works when it was available. Now in 2018, fitness is specialized and nutrition is scientific. The trade-off? Be careful what’s in your supplements, because a negative drug test can take you out for good. What hasn’t changed is that to be a winner, you still must ride the bike—a lot. Some may have bought into fitness as a substitute for riding, but the longest run or bicycle ride in the world won’t guarantee your throttle hand will twist when it’s needed.

Riding style

The riding style le jour in the early eighties was epitomized in riders such as Lechien, Barnett, O’Mara, and Bailey: technical, with the Gary Bailey Riding School “elbows up and out” profile on the bike. I’d suggest some of that is still the same, most exemplified in Eli Tomac. That guy cannot take a bad photo. His form on the bike is aggressive, many times up and over the tank. Nonetheless, there is something alternative emerging. It was showcased by Jason Anderson in route to his AMA Supercross Championship and was once again prevalent in Aaron Plessinger’s technique at Spring Creek. Frankly, it’s not pretty and doesn’t show as part of a clean, technical style. More akin to downhill mountain bike racing, it’s the butt extended well back over the rear fender, which encourages carrying the front wheel well beyond what has been previously considered efficient. I’d suggest this riding adaptation wouldn’t pass muster, but when champions are performing well using it, who am I to judge? Prepare to see much more of the butt-back, front-wheel-in-the-air style at Lucas Oil Pro Motocross.

Riding Apparel and Equipment

Riding gear has progressed, but it is not necessarily more appealing to fans. Most is now loose-fit with high tech-fabrics. Design is varied. Some of the outfits at Millville were retro-inspired—check out the back-to-basics logo design in Fox apparel. Injury prevention products came, went, and are partially back. Other than face and chest protectors, little existed at Spring Creek in 1983. What happened to the neck protectors and braces? Technology in boots and helmets is improved, which is necessary based on four-stroke machinery.

Motorcycles

Four-stroke technology: It wasn’t on the track in 1983. All three national classes featured two-stroke race bikes. Engines are somewhat comparable in performance and speed. For example, one magazine test indicated a Honda 450 four-stroke makes 58 horsepower while a Honda 500 two-stroke produces 60 horsepower. Of course, the power distribution is notably different. One of the major issues related in the progression of four-stroke racing is the associated costs and burden to privateers. Rebuilds cost thousands of dollars, and some racers suggest bikes used in the 250 Class at the national level have five-hour engines. This presents a long leap from 1983, when father and son could tear down and rebuild a two-stroke with affordable parts and minimal tools. In an economic sense, the entry cost to market has greatly increased.

Track design

The Spring Creek track was initially designed to accentuate the natural terrain of the area. There is significant elevation change on the course, which showcased a major uphill and downhill. The state of the sport now calls for more fabricated designs that put riders into the air. It’s interesting to note how the visual show has changed over the past 35 years. The track was well-prepped at both events, with respect to event promoter (and 1985 AMA National Hare Scrambles Champion) John Martin. But in modern times, the track grooves up in a significant way. I attended the post-event press conference with Tomac, Roczen, and Musquin following the 2018 event. All three commented on the terrifying aspect of riding the big three-story downhill at high speed, then threading into one of the ruts at the bottom.

Injuries

There seem to be more, and of those injuries, most are more significant. There were broken bones and sprains to deal with in the eighties, but anything past that was career-ending. Improved medical technology keeps more racers coming back. Look across the plethora of broken hips, femurs, pelvis bones, and arms. Tomac is riding with reconstructed shoulders, having had rotator cuff surgery on both sides. Roczen is another story. This bionic man has had one arm and one hand reconstructed. We can agree, all the king’s horses and all the king’s men would not have put Humpty Dumpty (Roczen) back together again… in 1983. Roczen recently commented after one of his top moto finishes, that it wasn’t bad “for a guy with two half-arms.” Amazing dedication coupled with reconstructive surgery that just wasn’t there in the eighties.

Rider mental state

Winners remain winners; they come to the party to race. A champion’s performance always rises to the occasion. In 1983, there were three to five riders in each class who had the potential to win. In 2018, three are on top in the 450s and in the 250s, two or three are probable while several others are possible outliers who, on the right day, might win. Beyond champion-status riders, riders may prove to be less resilient and more dependent on external input and encouragement. This isn’t my attempt to ridicule young riders; it is a broad hypothesis on the psychological state of what has been labeled iGen. If you’re interested in more of this, you may enjoy iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us, by Jean M. Twenge. Or, you can take my word for it.

Mobile communication

We didn’t have any in 1983. Well, not before mobile bag phones were available in the early nineties. Of course, we didn’t know any better. In 2018, the challenge continues with no mobile communication at Spring Creek. This time, I know what I’m missing. If my Verizon service doesn’t operate, my data feed is dead. I couldn’t text to locate where my brother was at the facility. How exposed we can feel, when our little portal to the world is inoperable…

Racetrack food

Racetrack food has remained some parallel to bar food, which is uniformly average. I can’t remember for sure—did Spring Creek have the stands selling those huge grilled turkey legs in 1983? I sure enjoyed watching fans go all cave man on those huge chunks of bird meat at this year’s event. I bought a $4 coconut shaved ice, served to me sans the coconut. Also tried a serving of fries served cold, hard, and swimming in vegetable oil. My redemptive food source became a small stand with a freezer which contained frozen fruit bars for $2. Winning.

Fans

Probably more subdued. I saw a few spectators stumble down the hill when the wheels on their cooler caught on a rock, but that’s the exception. Possibly more passive, but surely more artistically adorned. Tattoos are everywhere. When temps are hot, less clothes are needed and tats make the show, head to toe. If I was forced to make an educated guess, I’d suggest women have it all over men with the tat adornment. Tobacco use is greatly decreased. The cloud of haze that used to emanate from the crowds is, for the most part, dispersed. A bit of vaping mist in the air, but not enough to be a bother!