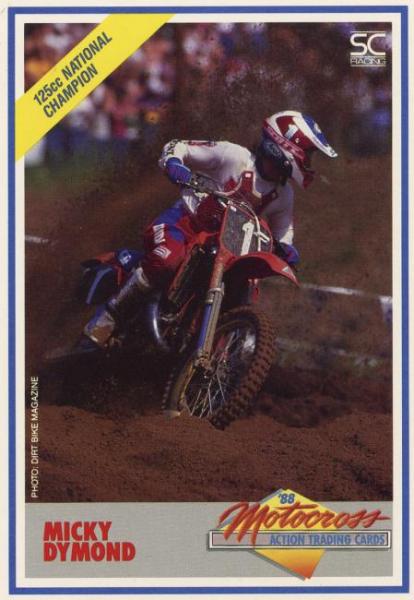

Dymond was also one of the most stylish riders of the ‘80s, but was suddenly dropped by Honda after winning the 125 National title in ’87. He slowly fell off the motocross map. After several years in the weeds and away from sport, he came back in the late 1990s and later won a Supermoto championship in 2005, marking eighteen years between AMA Pro championships!

I recently ran into Dymond in the grand stands while watching a flat track race at the Santa Rosa Mile. He indicated he had recently moved to Santa Rosa and heard the bikes from his living room, so he came to check it out. Dymond is one of the introspective and thoughtful racers that I have had the chance to interview. His latest project is perhaps his biggest physical challenge ever, but he is clearly up to the task.

Racer X: Micky, hey, what’s going on? What are you doing at a random flat track race and what are you up to these days?

Micky Dymond: Well, I just recently moved up north and here to Santa Rosa. I have been working on a big cycling project, which led me here in a lot of ways. I have always lived in Orange County, but wanted to make a change, and this area [Marin County] is one of the best places to ride and train on bicycles. I am pursuing a cycling event, which is called The Race Across America or RAAM for short. It is a combined project, and is a very strategic and long running athletic program. It will take me over a year to plan and complete.

This is one of those super gnarly, mega endurance events, right? Tell me how it works and what you will be up against?

Well, the race will happen in June of 2014. And basically you ride your bicycle across America. It starts in Oceanside, California on June 10 and finishes in Annapolis, Maryland. The goal is make it across in nine days—which averages to about 300 miles a day. But if you are riding it solo and don’t make it in 12 days, then you do not get credit for completing the event. It’s really grueling—there is very little sleep involved, and the weather has been known to destroy people. The whole thing is non-stop until you make it to Annapolis. It is considered one of the toughest athletic races in the world.

A surprise pickup by Honda, Dymond ran to the 1986 125 National Championship.

Kinney Jones photo

Wow! That’s crazy.

Yeah, it’s all about preparation and planning. I had read about it last year, and was really impressed and in awe of the guys who did it. But I was more in love with the idea of the event than actually doing it, but then the opportunity came about to actually do it, and here I am. In a Forrest Gump type of way, I got this opportunity and had to think quickly if I wanted to do it. So now it’s all about the prep, and getting ready for June 2014. For me, it has just been really interesting to get to know what goes on outside the sport of motorcycles. In motorcycle racing, you are always focused on yourself, and that’s it. But outside of racing (motor) bikes, there is a ton of other stuff going on, and I am getting older.

How did this come about?

Well, my girlfriend, Brenda Lyons, she was a pro cyclist and is now a trainer. She went to work for a group called Cardo Systems and Scala. It led her to the Ultra Cycling World, and that is what opened our eyes to the whole thing. It was pretty crazy at first.

Were you able to attend this year’s event to check it out?

Yeah. I followed it this year in a vehicle and it was gnarly—I watched some of the greatest athletes I have ever known just completely crumble. The sleep deprivation and the weather—it was nasty. Everything I am doing is more scientific than I thought it would ever be. I have everything laid out to get it done. Because of who we are as motorcycle racers and how tough we are, I think I can pick up the slack that might come up, you know, the hard stuff. And I am getting tougher as I get older. But I expect to get in there and get it done and finish it, but not to set any records. I just want the medal that says I finished.

So, is this a full time job for you right now or are you doing other stuff?

It is full time, but I do still have to work for a living. My day job is doing the planning and organizing for the Nuclear Cowboyz show that Feld does. We have our rehearsals in November and December this year. It is all new this year, and the show runs from January to April. So I have to balance doing a lot of different things and keep training, and most importantly, stay healthy and safe.

So no more Supermoto racing for you?

Actually, no! I am going to Belgium next week to do the Superbikes event. This is the fifth time I have done it. It is a really cool deal, a lot of great racers have been invited, and it is a big deal and honor to be included. I am racing against guys like Mickael Pichon, Stefan Everts, Troy Corser, Ben Bostrom, Chris Fillmore and Jeff Ward, as well as some of the really big names of European Supermoto. And the best part about it, at the end of the day, we can all have a beer and talk about the racing and have fun. It’s not as crazy as when we were younger!

In 2005, you won an AMA Pro Supermoto Championship. Tell me about that.

Yes, I rode the entire AMA Supermoto series for as long as it was around. It was a really good series and I enjoyed it immensely. I won the Unlimited title, which is basically the Open Class. The big bikes were really something—we rode a factory KTM 610, and man, it made some horsepower. But I have done other stuff in addition to supermoto—including the Baja 1000, and I won at Pikes Peak, as well.

He successfully defended that title in '87, but Honda didn't bring him back for '88.

Thom Veety photo

Your talent as a motorcycle rider runs deep. From motocross to freestyle, to Baja to supermoto, to Pikes Peak, it seems you are really gifted at riding. But let’s switch gears here and talk about Maico and Husky and your early motocross days. How did you parlay rides from both Husky and Maico into a factory Honda ride back in 1986?

Well, as we all know, the traditional way to get a ride is to start with Loretta’s. But I never did any of that. As a kid, I just rode the bikes that my dad liked, and what he got for me. Pro Circuit used to be Anaheim Husky, and Mitch [Payton] was instrumental in my career back then, before he hit it big with Team Peak. He hung out with all the MXA guys and the crew was all like family back then. Wheelsmith Maico was in Fountain Valley, and on paper a lot more untraditional than it actually was as the time. Those people were all supporting racers in Southern California, and I was one of them. With Indian Dunes and Saddleback racing several times per week, there was just all kinds of stuff going on in SoCal, and the support I had was European. I was able to parlay that into someone suggesting my name to Roger [DeCoster] and Honda, and it went from there.

But I remember I was close on that Husky, and that is how I got the Honda ride. The Husky, that was some of the best times of my career. I was working with Dick Burleson and Mark Blackwell, two legendary guys who were looking out for me. I was 16 years old and what did I know?

What do you remember about your time at Team Honda?

I had such a great career when I transitioned from Husky to Honda, but the Honda was so damn good. I was on factory Honda. The bike was unbeatable, and I felt that way about myself—no one could beat me. Riding for Team Honda at that time, well, you were on Honda, you were supposed to win. You had no excuses if you did not. The team was working really well, Roger and Dave [Arnold] were running things, and it was just a good environment to be in. It was a real pleasure to be part of that group.

But then you got dumped by those guys after delivering two straight titles?

Pretty much. The team was contracting because bike sales were slowing down. I won two 125cc championships, and the rules said I had to move to up to 250s. The team had gone from eight riders to four riders, and then I got bumped out because they wanted to drop to two riders. So I went to Yamaha—it was like going back to Husky or something. The bike was okay, but it was not a winning bike like the Honda was. That was a tough year for me. I felt betrayed that Honda did not want me, and I was hungry. The Yamaha had a great motor but did not handle well. It was not as good as the Honda was. It was a tough transition to go from Honda to anything at that time. Especially when you felt you had delivered for them, but then I got dumped. I actually felt I got used. I don’t know how many riders in today’s age have to deal with the same thing. But I was in heaven at the time, I got paid and won races, and was the best in the world. Suddenly, I am out of a ride and don’t have anything. And the business of the sport stepped in. All of a sudden, I was not into it, and was over it. That was my moment of growing up. It sucked.

It was nothing personal—but it was devastating. You have this whole floor that you based your life on, and that was yanked away from me. Yamaha wanted me and treated me great, but the bike was just not great. And I was still a child in many ways. We stated out strong, I was flashy, Troy lee was painting my helmets, Answer had some cool gear and I had a really cool visual impact. But then early in the season I fell off and broke my hand. That injury was basically a season ender, but then I tried to come back too early. It was not good.

But then I recall the media was talking about you and saying you were not taking racing seriously. Those were the days of big hair and glam rock, and one of the magazines was saying some nasty stuff about you.

Yeah, I had some other things going on. I was hanging with the Motley Crue guys, and basically people were saying I was running with the wrong crowd. I had a bad couple of years results wise, but was really on the cusp of being good. But it just created tension between me and the team. I was slightly off, people said I was way off, but [either way] it was not enough. That whole Motley Crue thing got overblown. My friendship with them was real, those guys were cool. It was not about hanging out or partying. We did a lot of constructive things, but because it was Motley Crue, people thought it was bad thing. I had a few surprise stress tests, the team was hearing rumors and it was total BS. It was a matter of not being to my ride at my full potential. You know, a lot of riders who do not last very long, it starts with a black eye. That is one of the sad things about the sport.

So you were in a pretty rough place at the end of your two years with Yamaha then?

Oh, for sure. You know, some guys—their guidance system is off, the way they come in and they don’t know any better. Guys like Jason Lawrence—they don’t last long, it’s an unforgiving machine the sport of motocross. A slight degree of separation from reality makes a huge difference. The guys that make it, God bless ‘em. During my time, the innocence was a lot easier to maintain, there was not so many false images as what you have now. Back then, your results were all that mattered, but today that is not entirely the deal. Results are hard to beat though!

An '87 shot for his '88 trading card. Dymond was never lacking for style.

So, you pretty much walked away after 1991 or so, and you disappeared from the sport. That was about five years before freestyle came around. Do you think if you had another outlet, such as FMX, that you would have gone that way?

I came home from Europe and was done. I went to school out in Palm Springs. I bought a place with the money I had earned, I met a women and we got married. We were married for 18 years. We had three kids, and that was my transition out of racing. Then in 1993, I went to work for my dad. His business is Dymond framing, and it was our family thing. My dad does not get credit for being the saint that he is. He was there and made a difference for me when I needed it.

Then in 1995, I think Jaime Dobb offered me his bike and I did a few vet races. Then I stared doing the Crusty films, and got back into it that way. Then the story gets dark for five or six years with me. It was really dark. But I was into the freestyle thing and was the first guy who built the steel ramps used today. I designed the first two X Games courses in San Francisco, and that basically got me back going again, and helped me form who I am today.

What is your relationship with the company All Access?

Well, around 2000, I met those guys through Tony Hawk. They are a rock and roll staging company. Back in 2001 or so, I did the Tony Hawk Boom Boom Huck Jams, I was working on the motorcycle portion of his shows. That got me on the right track. But that was when the AMA Supermoto came around, and All Access guys helped me design jumps and what not for that series. And I started racing again, and I was taking care of myself again, it continued to snow ball, my fitness, my health—it all came back after several years of not looking at that stuff.

All Access is a worldwide provider of staging for live concerts and events. They do stuff for American Idol and The Voice. Basically, they built the entire set. They even built the Super Bowl half time set. They do stuff for Madonna and Beyonce, Justin Beiber, just basically a huge rock and roll staging company. They keep me working, and the guys are awesome over there. Some important critical moments of my life, those guys have been there for me.

So what did you think of the mile racing? I think there is something special about the Mile’s, but the first Mile race I attended, I saw a racer lose his life right in front of me. It was at Duquin, Illinois, Davey Camlin went down in a pile up...

That [flat track] was one of my first hooks of feeling awe in motorcycle racing. The On Any Sunday footage of dirt track really inspired me as a kid. I caught the Dash the Cash, and man, they never let off, they ride into the first turn wide open with the tires spinning. It is such a crazy, incredible deal. Watching for the first time a real mile event is awe-inspiring.

You know, the danger is what really gets you. I spoke about this with God a lot, but that’s not reality on a regular basis. Anyone that has done this [motorcycle racing] has earned the right, and I just appreciate the reality of this thing. No prejudice of any types. Anytime you are riding on two wheels, it is a potentially dangerous situation.

I have seen the darkest side of the sport—friends who land in chairs, like Brian Manley, Tony D, Gary Butcher, Danny Magoo [Chandler], David Bailey, and the others who did not make it—guys like Mike Cinqumars, Jeff Kargola [OX], Jim McNeil, Caleb Moore and even Carey Hart’s brother, Tony Hart. There is no race that is worth a man’s life, but it is what is. Those were guys that were all close to me and that I knew very well. It is just what we do and what we love. It is not penalty, it just comes from doing what you live to do.

I agree there is no race that is worth a man’s life, but the things we do and the way we live our lives, it does not make it stupid or foolish—it just happens. I have seen some horrible things happen that I can’t get my head around, but I am human and maybe I can’t get my head all the way around, maybe that’s the way it is. Penalty is the word I guess—but I don’t have the answers for that.

On pretty much any form of two wheels, Micky still goes strong.

Simon Cudby photo

Wow … let’s move on from that. Tell me about your kids. Do they ride?

Yeah, I know … heavy stuff. My kids are all awesome kids, but none of them got into the bikes, the boys are hockey players and my daughter is a dancer. I co-parent three kids with my ex-wife. My oldest son Hunter is 21, my middle son Trevor is 18 and my daughter Ronni is 14. And I miss them a lot, I don’t see them every day like I used to since I moved north. But I have been able to live a charmed life, doing Nuclear Cowboyz, or Pikes Peak, or a bike race, but still just trying to grow as a person. It is not easy being a parent and adult. I am not wealthy. I am going to need to work until I die, but I spend my life being around new challenges, but at the same time, my kids mean everything to me.

How was the money for you when you were on top of racing?

I got paid well from Honda, and people treated me well. I did not go to school, I rode dirt bikes, and I was not educated when I made and had the money. I did not blow it on cars and parties, I bought some real estate, but the timing was bad. I could not unload the properties when I needed to. So it was kind of a wash. You know, the money does not last forever, and spreading it out over ten years, it is not that much. But for the time, I did pretty well.

Well Micky, I have another ten questions to ask, but I have to wrap this up. Good luck with the projects and perhaps we can speak after you finish the bike race this coming June.

Thank you, and yeah, you are going to need to edit this down a bit!