We bumped into Kiedrowski in the Yoshimura Suzuki pits at a recent national, where he was putting together a new barbeque for the team to use. Mike likes to work!

Racer X: Hey, Mike, what’s going on? What brings you to out to the races this weekend, and why are you putting together a shiny new barbeque for Team Yoshimura Suzuki?

Mike Kiedrowski: Well, I’m here to hang out at the races and be a fan! I almost always try to make a few of these races. Actually, my old mechanic Shane Nalley, who I won four championships with, now drives the Yosh eighteen-wheeler. He was coming up past my house, so I hitched a ride out with him in the big rig and for the weekend. But this year he also picked me up and we went to Phoenix and Oakland as well, and in his truck. I guess I feel that all the years he helped me out, now I can help him setting you up the tent and just being involved. You don’t appreciate what all those team folks do for you until it is all over [laughs]!

Well, I guess you have some history with those trucks—you were one of the first riders who made the transition from a little box van to a big semi truck, when you rode for Kawi back in 1991 or whenever it was.

Yeah, that’s right! Kawi got that semi in 1991, and it was driven by George Ellis and his wife. For sure I was one of the first to ride out of a semi truck back then. It was so different! In the back in the box van, all you had was a fan and an ice cooler. Now, to see it evolve, all the top forty riders have one, or it seems they have a sponsor that has one. The motor homes, all that stuff has gotten so much better and bigger over the past few years.

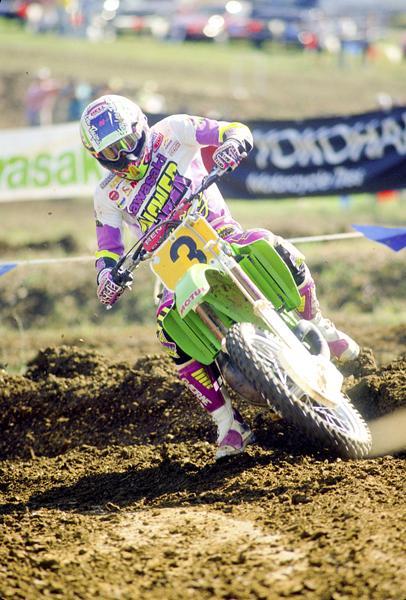

Kiedrowski won the 1989 125 National Championship, missed the '90 title by a point, then won it again in '91.

Thom Veety photo

Tell me about your family—you are married and a have a daughter, right?

That’s correct. My daughter, Kaitlin, is 15 and a huge Chad Reed fan. She really follows the sport closely, and I took her to meet Reed this year. She got a picture with him and I think it made her whole year! And I have been married sixteen years to my wife, Kim. We married in December of 1996. We met through Rob Healy of N-Style back in the day. She didn’t know anything about motocross back then and couldn’t have cared less about it, which I thought was pretty cool. And Kaitlin just finished the ninth grade at Valencia High School, and we live in Saugus, California, which is up north of L.A., by Magic Mountain.

So besides thumbing rides in big rigs, what are you up to?

I’ve been trying to get into the municipal fire service, but it’s been really tough to get hired. I’ve been working on it for the better part of five years, actually. I did the EMT thing and have taken all the fire-tech classes as well as the Swift Water Technician and the USAR classes. I’ve passed all my tests and have just been hanging out, being a father, and trying to get hired as a fireman. You know, it’s the same story, though: If there was an opportunity to get back into this sport, I would certainly consider it while I’m still working on the fireman deal. I still ride once a week or so, and luckily still have some sponsors that help me out—Troy Lee, 100% and Bevo, Dunlop, Suzuki, Renthal, Maxima. So that’s it. I’ve been keeping busy, though.

Tell me a little bit about your off road racing—it certainly extended your career a bit.

Yeah, it did. I was riding through the Suzuki off-road program, but Mike Webb and Pat Alexander have been good to me over the years, and I count them as great friends of mine. But first off, I wish I had stuck into moto just a little bit longer. I was actually talked into retirement back in the day.

Really? Explain that!

Well, at end of 1995 I was riding for Kawi, and I had a pretty good year. I was top five, but [Kawasaki] had plans to bring in some new racers for 1996. So basically, Brian Lunniss talked me into stepping away and taking a step back. He sort of convinced me my career was over at the time. It was my choice, of course, but I somehow started believing it, when perhaps it really wasn’t totally over. Now I look back and am not sure why I started thinking that way. But I retired at the end of 1995, and then in 1996 served as a contractor for Team Kawasaki and helped them out with the younger riders they had hired. But then I realized I still wanted to race and came back with Honda of Troy in 1997. Eric Kehoe was a good friend, and he was managing that team at the time. He and Rob Healy put together a small program for me and I came back. I knew they had good bikes, and the team was based closed to my house. But then I got hurt a lot that year. In fact, I got hurt more that year than my entire career, so I decided then in fact it was time to step away, because the injuries started messing with me.

That's (L to R) LaRocco, Kiedrowski and Bradshaw showing off late 80's pants style.

Thom Veety photo

So you quit MX in 1997 then. How did the off-road thing come about?

After I came back and got banged up a few times, I was then sure about my choice of quitting. My dad has always been a construction guy, and I went to work as an electrician in middle of 1998 with some friends. After three years of being an electrician, I came home from work one day and Mike Webb from Suzuki called me. I didn’t really know him, but Shane Nalley was there. Mike Webb was his boss, and they had the DR-Z400 coming out. They wanted a big-name rider to race the thing, and they asked me if I wanted to. My daughter was 2 years old, and I was feeling it, especially having worked the trades for three years! They had a super mellow and family oriented program, and along with Steve Hatch and Rodney Smith and it just looked appealing. The only thing was that it was a one-year deal, and I really knew nothing about off road, actually. But the guy I was doing electrical work with said to go for it and I could always come back.

How was the transition? MX guys are known to go fast off-road, but not for the long haul.

Totally. We started at the GNCC races, but the bike was too big and heavy. We finally started to figure out the bike and things were good. Yoshimura really stepped in and helped the effort out to get us some results. After a season or two, we then moved over the RM250 two-stroke for the GNCCs and stated to bring the DR-Z400 out west with the WORCS series. That bike was much better out west. I won two WORCS championships and also went to the ISDE and got a gold medal there. But Rodney Smith and Steve Hatch really worked with me and were a really, really big help. I think they didn’t like me at first, but then we all clicked. I’m still really tight with Rodney Smith—we talk once a week and hang out when we can. It was really one of my best teams I ever worked with, and I was lucky it lasted for several seasons.

Your riding career is pretty well-rounded. Are you the only national MX champion to get a gold medal at the ISDE?

I think so, yeah. I actually think I’m the only guy to represent America at both the ISDE and Motocross des Nations. I know Everts did it with Belgium, but I don’t think any other American has done it.

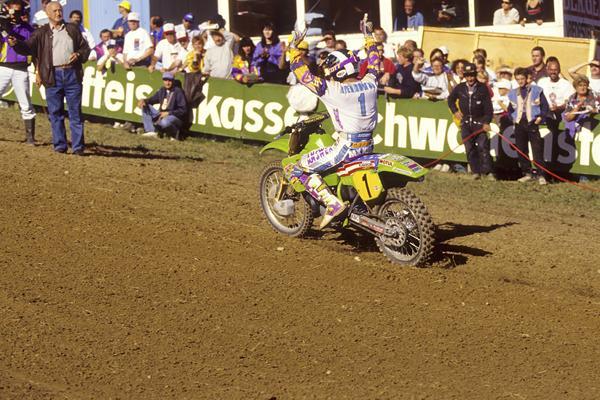

Kiedrowski's jump from 762 to #1 is one of the all-time biggest number drops.

Thom Veety photo

Now that’s a piece of trivia right here. How hard was the transition between pro motocross and pro off-road?

In a motocross or supercross, it’s twenty laps or thirty minutes, but you know its gonna be over soon. But at GNCC it’s three hours or longer. You’re working just hard as in moto—you’re breathing just as hard. But then in GNCC it’s like this: You’re thinking about the trail, so you aren’t drinking from your Camelbak. Then, about halfway through, when you stop for gas, your gear is all wet, your hands are blistered, and you’re a mess. You can start feeling yourself cramping up, but it’s too late—you’re done and your ass is sore. Cramps are setting in. Now you’re just trying to survive, and you start dropping like a rock. There’s one more lap left and you’re just done. It’s super hard. You make the finish and you can’t get off. You have blisters and you feel miserable and you can’t get undressed.

At that point, motocross wasn’t that tough. But now you have to suck it up—and then you have Smith and Hatch laughing at you! Those guys really helped me get better at it. I had a lot of fun, but I had more fun because of the team. It was just a good dynamic. We kept pumping each other up and the results followed. You go from motocross as a champion, but the existing off-road guys are territorial, and you get treated differently. But on the flip side, the MX guys are wondering why you’re going to off-road racing, and they think you’re one of those off-road weirdos. It’s funny, you get the feeling from both sides. But the off-road guys didn’t want me to come in and think I was better then them. They wanted to put me in my place.

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but I could see that for sure.

I can relate this back to getting into the fire service. I think sometimes those guys thought because I had all these championships and was on television and made money racing dirt bikes, they thought I would have it easy and would be lazy or something. But that’s not the case. I think that being a big name with some success in another field actually kinda hurt me, if you can believe it. I don’t think I’m any better than anyone else, and I really like working with my hands and feel that I’m also quite mechanically inclined. And I felt that same way in off road, until I was able to prove myself and those guys accepted me.

What are some of your best memories from your career?

Probably the best was winning my first championship in 1989. It was a huge accomplishment. I was basically a top-twenty rider who had just moved up from the amateur races. Then Honda hires me and I went out and won the first national, which surprised a lot of people—including myself! That year, I actually rode for Mitch Payton and ran the Pro Circuit pipe, cylinder, and head. George Holland, Jeff Stanton, and Ricky Johnson were the real factory guys, but Honda gave us one-year-old works suspension and some old box vans they had. That year it was me, Larry Ward, and Guy Cooper with a support ride and some help from Pro Circuit.

That was before Mitch had his Peak Pro Circuit team, right?

Yup. That was before he started his own deal. My next biggest one was probably 1993 250 championship. I was dominant that year. I think I had a little bit of Carmichael in me [laughs]. I went to the line asking myself, “How far am I going to win by today?” I just had that feeling, and it all came together, which is a really cool memory to have. That mindset is such a great place to be, knowing that you can go out and win, and that season was just special in that way. I also like 1994 when I was battling LaRocco and we were both about a half lap ahead of Jeremy [McGrath] every weekend, which gave us some redemption for the beating he gave us in supercross.

On 250s and 500s Kiedrowski was a formidable force. He won some supercrosses, too.

Jim Talkington photo

What do you think about the sport today?

Things have changed a lot—the tracks’ layout is way better for fans and more fan-oriented. When I was here there were no bleachers and it was just a bit more raw. But now the sport is media-driven and much more focused on the fans. When I was racing, you heard about it a month later, but now news is available all the time. I think the riders and the fans get to come in the pits. I think it’s great. It’s getting better. Riders still have the pressure and are getting paid a lot more money.

What do you think about the parents and family involvement and entourages today at the top level of the sport?

When I was signed, my first deal with Honda in ‘88, my parents said I was on my own! They didn’t follow me to the races—they basically just threw me out. They helped me out for sure, but they let me go. They never asked for anything back, and it was great. Now you have parents on the payroll for these riders. For my parents, they got me to a certain point, but then they were done—my first paid contract and they were out, 100 percent. Bevo [Forti] was the only guy that did anything. For me, that was it. I had to call Answer every week and order my gear—and hope it got to my house in time! I used to stick stickers on my helmet and chest protector. I had to call Troy Lee and ask for a helmet when mine got banged up from rocks, and he would paint me a new one but it took a few weeks.

How was the money for you?

It was great! I made good money. It was good. I made more than the guys before me, and now the guys after me are doing the same. We were on the verge. We didn’t have the big sponsors, the Rockstars the Red Bulls. That’s why I kinda wish I had stayed in MX—maybe I could have gotten some of that money! But the riders are the same. The four-strokes are faster—when they crash, they crash harder. For me, motocross was more lucrative, but the money with Suzuki off-road was also really good. We were paid very well for what we did. So that was a good deal for sure. The money goes quick. Dave [Stephenson, Kiedrowski’s agent] put mine away and I was regimented. I think guys don’t realize how quickly it goes away and how easy it is to spend it.

Kiedrowski was a hero on MXdN teams in 1989 and 1991, and he also scored an ISDE medal in 2003.

Racer X Archives

What’s your stance on the neck brace?

I’m 50/50 on it. I used it for off-road. It was tough. I found it restrictive. I wear a Leatt-Brace when I ride MX, but when I ride off-road I usually don’t wear it. I don’t think there’s anything bad about it, though, but I’ve heard rumors about what injuries it might have contributed to or whatever. But overall I think it’s a good thing. For young kids racing, they should be wearing it. That’s the bottom line.

Thanks, Mike. This is longer than it should be, but it was great chatting with you!

Yeah, it’s crazy how it works out in the end! But hey, my door is open and it would be cool to get a gig like Stanton and Barcia have, or how Lusk and Millsaps work together. If anyone is interested, have them get a hold of me!