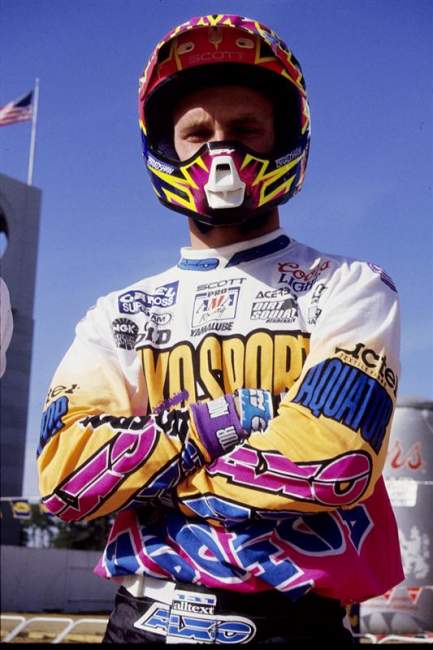

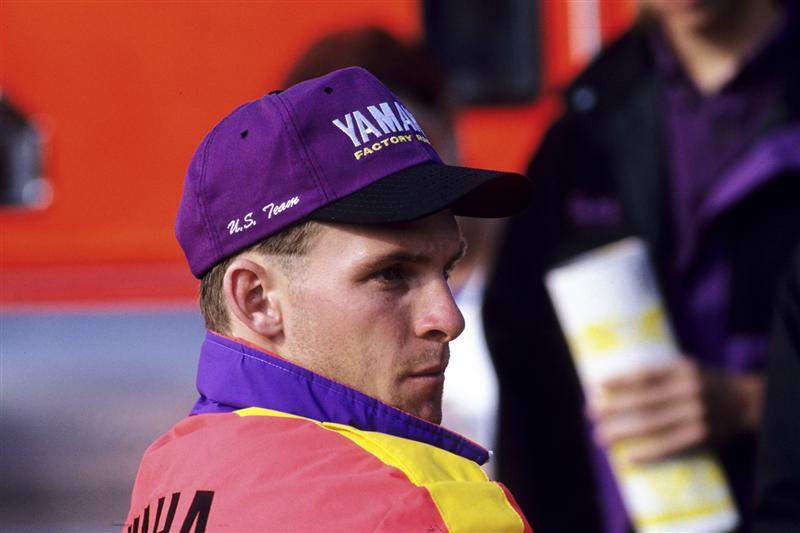

If you need to be informed who Damon Bradshaw is, you probably think motocross machines have always had valves. With Anaheim I coming up this weekend, we decided to give a jingle over to The Beast from the East (now from west of a lot of places, in Idaho) and talk to him a bit about his first win at the Anaheim season opener, 20 years ago in 1990, when he was 17 years old. And then one thing led to another... Pull up a chair, because if you read all of this (and you should), you’re going to be here a while. Here it is: 30 Minutes with Damon Bradshaw, today's (late because we talked too much) Between the Motos.

Racer X: Anaheim I is coming up this weekend, and I was in the audience in 1990 when you were 17 years old and came out and dominated this race. It’s now 20 years ago! Can you give us some perspective as to what Anaheim means when it’s the series opener like that, in the industry center, and all of that?

Damon Bradshaw: It meant a great deal. The difference was that nowadays it seems like the guys race against each other more before Anaheim [the U.S. Open, and other such events] than what we did back then. Back then, the season was over, and you might do a few races in Europe here and there, but very rarely was everybody there that you were going to race against at Anaheim. That happens more now, where it seems like there’s more racing and less secrets, whether it’s the bikes, or you were riding better than in years past... Anaheim was like a big surprise to everyone because you didn’t know what was going to happen, or who was going to be the guy, and to win, or to do really well, that set the precedent for nearly the whole season. And remember, back then, we had supercross and outdoors sort of mixed together, so it would help you even outdoors. But now, for supercross, Anaheim is probably even more important, because you do the whole supercross series before going outdoors at all, so it really sets a strong precedent. It’s not just confidence for you when you do well, but it puts everybody else in the “I wonder” category.

Your race seemed like exactly that, where you just killed everyone and no one saw it coming. You won in Tokyo or Osaka before that, but no one could’ve figured you were going to go out and do that.

And I just know that race was as important as any other race throughout the year – even the last one – just because it set the stage, and then everybody based the year on it. Now, whether you ended up winning many races after that, it didn’t matter sometimes, because at Anaheim, it was the first event, and it was in front of the industry. It was like winning a Daytona or a Vegas in the end. Also, I was 17 years old, so it actually really helped me that I had everything to gain and nothing to lose. If I’d have gone out and gotten 10th, it really wouldn’t have been that big of a deal, because I was 17. Even though I was expected to do well, I knew I didn’t have to do it right away. There was pressure, but nothing like years after that when we went to Anaheim. That first Anaheim, to me, was probably the most relaxed one that I’d ever ridden. But after you win once, then people expect it.

That’s good and bad. Bob Hannah said before that after he won his first race, “I’m no idiot, so I knew I could do it again.” But at the same time, everyone else’s expectations rise, too.

I was the worst on myself. I put so much pressure on myself. And really, it came from nowhere else. It wasn’t from Yamaha until later on in my career when my results weren’t good and my head wasn’t there. Then I started getting pressure. But early on in my career, I did it to myself. It became where it was expected. I remember like it was yesterday, we were standing on the podium in Osaka, and I had won and Ricky [Johnson] was second, and I don’t really even remember who was third, but me and Ricky were friends since I was still on minibikes, and he was already racing supercross and nationals then. Anyway, we were standing on the podium, and he was talking to me like I was a little kid, and the last part of the conversation, he said, “Well, now this is expected of you, and when you don’t, everybody’s going to want to know what happened.” And he was right, because whether you were calling home after the event, or calling your parents, or calling your friends, if you didn’t win, they wanted to know what happened! You get third or fourth, and they’re like, “Well, why didn’t you win?!” (Laughs) But those first few races [in 1990] were really fun, and even the one in Japan was, because I had nothing to lose. It seems like later on, I put the pressure on myself, and it’s probably part of the reason I got burnt out in as short of an amount of time as I did, because I put so much pressure on myself and I expected so much out of myself every time I was on the bike.

I went through this recently with Josh Hill, who went through a rough patch because he just got burnt out, and a lot of people were saying, “Well, Josh should just suck it up and do it because he’s getting paid, and that’s that.” They think it’s ridiculous that a kid could get burnt out “that fast” in his career, but the reality is that it’s not just three or four years to him. He’s been racing full-time since he was a little kid. It’s the same for you when you came through, right?

That’s exactly right, and more than likely he did it similar to how we did it, because my dad had us traveling all over. And sure, that’s probably what got me so good at such a young age, but for many years, I was way younger than everybody, so I got beat a lot. I got beat continually. That was hard for a kid. It’s a lot like playing football. You’ve got to eventually win and get the taste of victory. So I looked back on when I actually did step away, or retire, or whatever you want to call it, and I look at all of those years, and it was pretty damned serious for me at a really young age. It wasn’t like at four, but it wasn’t too far after that that it became serious enough that my parents were thinking that I had a chance to do something. And as young as 13, or maybe even before that, I was already thinking ahead to supercross. Early on, I was thinking, “Hey, I can do this.” It’s not like it was just five years, it was a lot more, and it adds up. But because you hit it so hard at such a young age, you don’t get to be a kid – and more than likely a lot of that probably kept me out of trouble – but you miss out on a lot of stuff that most people don’t even take into consideration.

Well, you and I are in our 30s now, and it’s easy to look at Josh Hill or any of these other guys and think, “If I had the talent, then I would...” But you can’t just take the talent. Josh Hill doesn’t have the life experience we have. If you’re going to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, you have to actually put their shoes on, not just the part you want. It was probably the same with critics in the early ‘90s for you.

Yeah, and since I’ve been in that position, at my age now, after I’ve seen it all and been a part of it, I’ve talked to Yamaha about it probably two years ago to try and go talk to some of the kids, and even their parents, about all of this. I mean, I’m no psychologist, but I’ve been through a fair amount in my career, and I’d love to go talk to these kids and help them because I’ve pretty much been through everything they’re going to go through, from hating what you’re doing to loving what you’re doing, from hating your parents to loving your parents, and all that stuff. I don’t know what the deal is with Josh, but I do think I can usually give some insight to those people, either from the position of the rider or of their parents. Some of them, or more than a lot of them, would benefit from it. When I was young, I tried to listen to everyone no matter where they were coming from. I tried to listen to everyone because I felt like they didn’t really have to be doing or even know what I did, but they could possibly give me some advice that would help in whatever I was doing.

Ultimately, it’s up to you to filter it out.

Yeah, but I’m sure there are a lot of people who don’t look at it that way. I’ve gotten it from my oldest son. I don’t play football, and I’ve never played football, but still, the will to win, and the effort, and being serious with it, it’s all part of it. It’s all part of winning. And I would try and tell him that, and I’d talk to him about football, and he’d say, “Dad, you never played football!” So I’d have to go through the whole thing and explain to him what it meant to win, what it takes to win, the right attitude, and all that. But it’s a team sport, and that’s one thing I did like about a motorcycle, which is that once you threw your leg over the bike and the gate dropped, it was you. It’s still a team effort, but you can’t hand off to your buddy and say, “Now you ride for a while.”

I think that’s something that’s genuinely different about motocross racers, or maybe racers in general, which is that they’d rather lose because something is their fault than win because of something outside of their control...

Yeah, you want total control. You can go through all of these scenarios over the years, and it’s funny how you’re supplied with bikes that weren’t up to snuff sometimes. There were a couple of times that I was supplied with 125s in ’89 where things just weren’t up to par, and with motorcycles, you could make up for a lot of that. It’s not like going and racing a car, where if it’s not hooked up or it’s not running, you can forget about it. With a motorcycle, you can overcome some of that. I just remember how discouraging that was to ride something that wasn’t up to par, and I just felt like I was doing everything I could do, and it’s just not good enough. What can you do? You can’t do anything.

How many points short were you?

I think I was one point short outdoors behind [Mike] Kiedrowski, and two points in front of him in supercross, or maybe two points outdoors and one point in supercross, but it was close.

And I’m sure you can think of 10 or 20 different things that, if one of them went differently, you could’ve made up that one or two points...

Yeah, but not as much that one as the year I lost the championship against [Jeff] Stanton and I was 27 points ahead with just a few races left [1992], going into Indianapolis. That was pretty late in the series, and I was a race ahead! But, hey, it is what it is...

But that’s kind of why I’m talking to you about Anaheim. Last year, James Stewart crashed out of Anaheim, but then still ended up winning the title, but he definitely made it hard on himself. You always hear the statement where people say you can’t win the championship at round one, but you can lose it.

Yeah, and I think it takes a strong guy, mentally and physically, to come back after not just one bad race, but when you have more than one in the beginning of the season, because I remember that year that Stanton was just struggling, and nothing was going his way. I remember seeing him walking around the pits, and I was obviously on top of the world because things were going my way, and my bikes were great, and my mechanic, and it couldn’t have been going any better, and I would see him and say, “Shit, man, it can’t only get better!” We were pretty good friends, and you talk about those things, and then later on, he ended up winning the championship, and I think he won four events or something.

Or three...

That’s just one of those things where it’s not just physical or mental, or bikes or whatever. It’s everything. It’s like I remember when Kevin Windham came onto the team, and he was such a mental guy – and I was pretty mental, too – but it was nice to be around him, because some other guys weren’t quite that way. But with Windham, you could turn his attitude around just by talking to him. He’d be down in the dirt, and you’d talk to him a little bit, and he’d have a totally different look in his eye, and you could totally see it when he threw his leg over his bike.

That’s actually a pretty famous thing with Kevin, which is if you see him in the morning at a race, and he’s all giddy and happy, there’s a really good chance he’s going to win...

Yeah, exactly, and I’ve always said that. That guy could go as fast as anybody on earth if he just wanted to all the time, because he was so damned smooth back then. But when something happens multiple times in the beginning of the year, like with Stanton, and to come back, that’s something. And then there are times when you have an injury and you have to ride through that, that was enough to mess me up, like one year I had a thumb injury pretty early on and I had to deal with it the whole season. It just sucked, because you’re always training and riding and it always hurts, so you’re thinking about it...

You say a “small thing” like a thumb injury, but a thumb injury is actually a pretty big pain in the ass in motocross...

Oh, yeah. I didn’t break it, but some dude doubled a triple and crashed, and then was laying on the triple landing, and I landed on his bike and it threw me over the bars and bent my thumb back. It was there until the off-season. Stupid stuff like that can change your whole mental approach, and it takes somebody like a [Brian] Lunniss, or somebody like that to turn your head around and help you forget about that and get over the mental anguish of being hurt. “If you can do it without it, you can do it with it,” or whatever.

It sounds to me like you’re actually complimenting Jeff Stanton for beating you that year, but I can’t imagine that’s how you felt at the time. How long did that take?

I think it definitely affected the rest of my career just because it was so close and I lost it like that, but I do think I always tried to give credit where credit was due. If I got beat, I got beat. That’s just the way it was, and that’s the way it ended up. Unfortunately, there were a lot of people who didn’t want to see me win that championship for whatever reason, and I’m sure Jeff was one of them, but he fought back from a terrible beginning of the year. But it’s crazy because when I’d see him walking the track or something, I felt bad for him, but in the end, he wins the damned championship later on. It was just one of those things where, when I crashed and lost the 27-point lead, I was jacking with Jeff at Indianapolis because I was just on, and so confident, that I felt that nothing could change the fact that I was going to win, and I was going to screw with him for a little bit, and then I was going to pass him and win the race. That was how confident I was, and it just bit me in the ass. I cross-rutted, and that was the end of the story over the triple.

It’s crazy how that works...

Yeah, and I know that Jeff probably thought I was being a prick – and I really was – but it was just one of those things where I was just continuing in confidence-building for me, and all Jeff kept doing was just trudge along like he always did.

So you can really look at that race as almost a turning point in your entire career, not just that season...

Oh, it was, for sure. As far as getting beat, that was easily gotten over, because the bottom line was that I rode bad at LA [the season finale, in the daytime due to the recent LA riots], and I had never ridden that bad under pressure. I mean, I dealt with pressure on minibikes, amateur nationals, and the mini Olympics, to where you had to win every last moto to have a chance at winning that deal. That sort of pressure was never a problem, and there was a lot of pressure at LA, not only from family and sponsors, but I had fallen at RedBud and tore my ACL and had to ride LA with that, too. But that wasn’t the deciding factor. That didn’t keep me from winning the championship. I just rode bad, and it all just came down from there.

Are you ever going to show up to one of these things and say, “Hey, guys, remember me?”

(Laughs) I have a couple of times, but it’s hard. Like this weekend, I leave Thursday, and I’ll be in Houston, and every time you guys are at a supercross, I’m at a monster truck event, so it’s tough. I get one weekend off, the third weekend in March, and then the World Finals in Vegas, but I doubt I’ll make it to any supercrosses, much less a few of them. It’s fun to go, usually, like the last time I went was at Salt Lake City last year, and if I remember right, it was pretty damned good racing in both classes, but I had been to a few before that where I was ready to go because it was boring as hell. It’s weird because I look at what I do now, and it’s a whole different fan base and show and everything else, but every so many minutes, there’s something else going on down on the floor. At a supercross, you have the qualifiers, and then there’s that dead time, and it’s so weird because I’m used to everything being driven on show flow now. Nowadays, I’m looking in the stands to see their response to whatever’s going on, but never would I ever thought of doing that at a supercross. It’s just a different mindset for me now. So when I go to a supercross, I’m sitting there thinking about what can be going on down on the floor to keep these people’s attention during that dead time, whether it’s freestyle motocross, or even back in my day, I would be in the stands walking around with four or five people signing things for the fans in the stands! How much does that happen now?! (Laughs)

I’d say, almost never...

Yeah, exactly, and I remember sponsors coming to me and asking what I think about this or that, and I’d usually be down to do it, because my thought going into the place at the beginning of the night was that even if you weren’t number one in the fans’ eyes at the beginning of the night, I wanted to be at the end of the night. So it would have to be something that happened or was said, and that was always my goal, to have as many people cheering for me as possible. It’s like the one year I went to Anaheim, and I was the last guy that I felt any of those people wanted to see win – you know, because of all the California boys – and I remember going into Anaheim – the old stadium that held so many people – and thinking, “I know they want to see Ricky [Johnson] win, because he lives just up the road.” And it was pretty cool because I remember one of those races at Anaheim that I won, I had to ride the qualifier, the semi and the last chance, and then I won the main event. I had to ride all of them. Shit, by the end of that night, I felt like I had everybody in the stadium on my side, and whether it was because I had to ride every race or what, it didn’t matter. I thought it was pretty damned cool. I still think about stuff like that now because Gravedigger, Dennis Anderson is like Dale Earnhardt Jr. or Dale Earnhardt Sr. in our business. If you go to a neutral motorsports event and you put Dale Earnhardt Jr. and Dennis Anderson side by side, their autograph lines would probably be very similar. That’s just how it works. I see that on a weekly basis, and I’m thinking all the time about getting more fans, what I can do, and how I can be more creative. Usually it’s from my driving, because I don’t get a lot of opportunities to talk to the people, but at a supercross, you could say just a couple of things and turn the people around completely. It could be talking shit to some other rider, or whatever, and you could turn them around. Then, it came naturally after a while, like between me and Chicken [Jeff Matiasevich] or some of the other guys. It started to just happen.

Rick Johnson told me that he always had a goal of playing to the crowd and turning fans around.

Yup, and it was really hard to have that total package. There weren’t that many guys, even to this day, who can work the crowd and still be fast enough to win. That’s the total package.

It definitely is, and this interview is going to have people sitting for 30 minutes trying to read.

Oh well! If you think of anything else, just give me a call.

Thanks, Beast.

You’re welcome.

Racer X: Anaheim I is coming up this weekend, and I was in the audience in 1990 when you were 17 years old and came out and dominated this race. It’s now 20 years ago! Can you give us some perspective as to what Anaheim means when it’s the series opener like that, in the industry center, and all of that?

Damon Bradshaw: It meant a great deal. The difference was that nowadays it seems like the guys race against each other more before Anaheim [the U.S. Open, and other such events] than what we did back then. Back then, the season was over, and you might do a few races in Europe here and there, but very rarely was everybody there that you were going to race against at Anaheim. That happens more now, where it seems like there’s more racing and less secrets, whether it’s the bikes, or you were riding better than in years past... Anaheim was like a big surprise to everyone because you didn’t know what was going to happen, or who was going to be the guy, and to win, or to do really well, that set the precedent for nearly the whole season. And remember, back then, we had supercross and outdoors sort of mixed together, so it would help you even outdoors. But now, for supercross, Anaheim is probably even more important, because you do the whole supercross series before going outdoors at all, so it really sets a strong precedent. It’s not just confidence for you when you do well, but it puts everybody else in the “I wonder” category.

Your race seemed like exactly that, where you just killed everyone and no one saw it coming. You won in Tokyo or Osaka before that, but no one could’ve figured you were going to go out and do that.

And I just know that race was as important as any other race throughout the year – even the last one – just because it set the stage, and then everybody based the year on it. Now, whether you ended up winning many races after that, it didn’t matter sometimes, because at Anaheim, it was the first event, and it was in front of the industry. It was like winning a Daytona or a Vegas in the end. Also, I was 17 years old, so it actually really helped me that I had everything to gain and nothing to lose. If I’d have gone out and gotten 10th, it really wouldn’t have been that big of a deal, because I was 17. Even though I was expected to do well, I knew I didn’t have to do it right away. There was pressure, but nothing like years after that when we went to Anaheim. That first Anaheim, to me, was probably the most relaxed one that I’d ever ridden. But after you win once, then people expect it.

That’s good and bad. Bob Hannah said before that after he won his first race, “I’m no idiot, so I knew I could do it again.” But at the same time, everyone else’s expectations rise, too.

I was the worst on myself. I put so much pressure on myself. And really, it came from nowhere else. It wasn’t from Yamaha until later on in my career when my results weren’t good and my head wasn’t there. Then I started getting pressure. But early on in my career, I did it to myself. It became where it was expected. I remember like it was yesterday, we were standing on the podium in Osaka, and I had won and Ricky [Johnson] was second, and I don’t really even remember who was third, but me and Ricky were friends since I was still on minibikes, and he was already racing supercross and nationals then. Anyway, we were standing on the podium, and he was talking to me like I was a little kid, and the last part of the conversation, he said, “Well, now this is expected of you, and when you don’t, everybody’s going to want to know what happened.” And he was right, because whether you were calling home after the event, or calling your parents, or calling your friends, if you didn’t win, they wanted to know what happened! You get third or fourth, and they’re like, “Well, why didn’t you win?!” (Laughs) But those first few races [in 1990] were really fun, and even the one in Japan was, because I had nothing to lose. It seems like later on, I put the pressure on myself, and it’s probably part of the reason I got burnt out in as short of an amount of time as I did, because I put so much pressure on myself and I expected so much out of myself every time I was on the bike.

I went through this recently with Josh Hill, who went through a rough patch because he just got burnt out, and a lot of people were saying, “Well, Josh should just suck it up and do it because he’s getting paid, and that’s that.” They think it’s ridiculous that a kid could get burnt out “that fast” in his career, but the reality is that it’s not just three or four years to him. He’s been racing full-time since he was a little kid. It’s the same for you when you came through, right?

That’s exactly right, and more than likely he did it similar to how we did it, because my dad had us traveling all over. And sure, that’s probably what got me so good at such a young age, but for many years, I was way younger than everybody, so I got beat a lot. I got beat continually. That was hard for a kid. It’s a lot like playing football. You’ve got to eventually win and get the taste of victory. So I looked back on when I actually did step away, or retire, or whatever you want to call it, and I look at all of those years, and it was pretty damned serious for me at a really young age. It wasn’t like at four, but it wasn’t too far after that that it became serious enough that my parents were thinking that I had a chance to do something. And as young as 13, or maybe even before that, I was already thinking ahead to supercross. Early on, I was thinking, “Hey, I can do this.” It’s not like it was just five years, it was a lot more, and it adds up. But because you hit it so hard at such a young age, you don’t get to be a kid – and more than likely a lot of that probably kept me out of trouble – but you miss out on a lot of stuff that most people don’t even take into consideration.

Well, you and I are in our 30s now, and it’s easy to look at Josh Hill or any of these other guys and think, “If I had the talent, then I would...” But you can’t just take the talent. Josh Hill doesn’t have the life experience we have. If you’re going to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, you have to actually put their shoes on, not just the part you want. It was probably the same with critics in the early ‘90s for you.

Yeah, and since I’ve been in that position, at my age now, after I’ve seen it all and been a part of it, I’ve talked to Yamaha about it probably two years ago to try and go talk to some of the kids, and even their parents, about all of this. I mean, I’m no psychologist, but I’ve been through a fair amount in my career, and I’d love to go talk to these kids and help them because I’ve pretty much been through everything they’re going to go through, from hating what you’re doing to loving what you’re doing, from hating your parents to loving your parents, and all that stuff. I don’t know what the deal is with Josh, but I do think I can usually give some insight to those people, either from the position of the rider or of their parents. Some of them, or more than a lot of them, would benefit from it. When I was young, I tried to listen to everyone no matter where they were coming from. I tried to listen to everyone because I felt like they didn’t really have to be doing or even know what I did, but they could possibly give me some advice that would help in whatever I was doing.

Ultimately, it’s up to you to filter it out.

Yeah, but I’m sure there are a lot of people who don’t look at it that way. I’ve gotten it from my oldest son. I don’t play football, and I’ve never played football, but still, the will to win, and the effort, and being serious with it, it’s all part of it. It’s all part of winning. And I would try and tell him that, and I’d talk to him about football, and he’d say, “Dad, you never played football!” So I’d have to go through the whole thing and explain to him what it meant to win, what it takes to win, the right attitude, and all that. But it’s a team sport, and that’s one thing I did like about a motorcycle, which is that once you threw your leg over the bike and the gate dropped, it was you. It’s still a team effort, but you can’t hand off to your buddy and say, “Now you ride for a while.”

I think that’s something that’s genuinely different about motocross racers, or maybe racers in general, which is that they’d rather lose because something is their fault than win because of something outside of their control...

Yeah, you want total control. You can go through all of these scenarios over the years, and it’s funny how you’re supplied with bikes that weren’t up to snuff sometimes. There were a couple of times that I was supplied with 125s in ’89 where things just weren’t up to par, and with motorcycles, you could make up for a lot of that. It’s not like going and racing a car, where if it’s not hooked up or it’s not running, you can forget about it. With a motorcycle, you can overcome some of that. I just remember how discouraging that was to ride something that wasn’t up to par, and I just felt like I was doing everything I could do, and it’s just not good enough. What can you do? You can’t do anything.

How many points short were you?

I think I was one point short outdoors behind [Mike] Kiedrowski, and two points in front of him in supercross, or maybe two points outdoors and one point in supercross, but it was close.

And I’m sure you can think of 10 or 20 different things that, if one of them went differently, you could’ve made up that one or two points...

Yeah, but not as much that one as the year I lost the championship against [Jeff] Stanton and I was 27 points ahead with just a few races left [1992], going into Indianapolis. That was pretty late in the series, and I was a race ahead! But, hey, it is what it is...

But that’s kind of why I’m talking to you about Anaheim. Last year, James Stewart crashed out of Anaheim, but then still ended up winning the title, but he definitely made it hard on himself. You always hear the statement where people say you can’t win the championship at round one, but you can lose it.

Yeah, and I think it takes a strong guy, mentally and physically, to come back after not just one bad race, but when you have more than one in the beginning of the season, because I remember that year that Stanton was just struggling, and nothing was going his way. I remember seeing him walking around the pits, and I was obviously on top of the world because things were going my way, and my bikes were great, and my mechanic, and it couldn’t have been going any better, and I would see him and say, “Shit, man, it can’t only get better!” We were pretty good friends, and you talk about those things, and then later on, he ended up winning the championship, and I think he won four events or something.

Or three...

That’s just one of those things where it’s not just physical or mental, or bikes or whatever. It’s everything. It’s like I remember when Kevin Windham came onto the team, and he was such a mental guy – and I was pretty mental, too – but it was nice to be around him, because some other guys weren’t quite that way. But with Windham, you could turn his attitude around just by talking to him. He’d be down in the dirt, and you’d talk to him a little bit, and he’d have a totally different look in his eye, and you could totally see it when he threw his leg over his bike.

That’s actually a pretty famous thing with Kevin, which is if you see him in the morning at a race, and he’s all giddy and happy, there’s a really good chance he’s going to win...

Yeah, exactly, and I’ve always said that. That guy could go as fast as anybody on earth if he just wanted to all the time, because he was so damned smooth back then. But when something happens multiple times in the beginning of the year, like with Stanton, and to come back, that’s something. And then there are times when you have an injury and you have to ride through that, that was enough to mess me up, like one year I had a thumb injury pretty early on and I had to deal with it the whole season. It just sucked, because you’re always training and riding and it always hurts, so you’re thinking about it...

You say a “small thing” like a thumb injury, but a thumb injury is actually a pretty big pain in the ass in motocross...

Oh, yeah. I didn’t break it, but some dude doubled a triple and crashed, and then was laying on the triple landing, and I landed on his bike and it threw me over the bars and bent my thumb back. It was there until the off-season. Stupid stuff like that can change your whole mental approach, and it takes somebody like a [Brian] Lunniss, or somebody like that to turn your head around and help you forget about that and get over the mental anguish of being hurt. “If you can do it without it, you can do it with it,” or whatever.

It sounds to me like you’re actually complimenting Jeff Stanton for beating you that year, but I can’t imagine that’s how you felt at the time. How long did that take?

I think it definitely affected the rest of my career just because it was so close and I lost it like that, but I do think I always tried to give credit where credit was due. If I got beat, I got beat. That’s just the way it was, and that’s the way it ended up. Unfortunately, there were a lot of people who didn’t want to see me win that championship for whatever reason, and I’m sure Jeff was one of them, but he fought back from a terrible beginning of the year. But it’s crazy because when I’d see him walking the track or something, I felt bad for him, but in the end, he wins the damned championship later on. It was just one of those things where, when I crashed and lost the 27-point lead, I was jacking with Jeff at Indianapolis because I was just on, and so confident, that I felt that nothing could change the fact that I was going to win, and I was going to screw with him for a little bit, and then I was going to pass him and win the race. That was how confident I was, and it just bit me in the ass. I cross-rutted, and that was the end of the story over the triple.

It’s crazy how that works...

Yeah, and I know that Jeff probably thought I was being a prick – and I really was – but it was just one of those things where I was just continuing in confidence-building for me, and all Jeff kept doing was just trudge along like he always did.

So you can really look at that race as almost a turning point in your entire career, not just that season...

Oh, it was, for sure. As far as getting beat, that was easily gotten over, because the bottom line was that I rode bad at LA [the season finale, in the daytime due to the recent LA riots], and I had never ridden that bad under pressure. I mean, I dealt with pressure on minibikes, amateur nationals, and the mini Olympics, to where you had to win every last moto to have a chance at winning that deal. That sort of pressure was never a problem, and there was a lot of pressure at LA, not only from family and sponsors, but I had fallen at RedBud and tore my ACL and had to ride LA with that, too. But that wasn’t the deciding factor. That didn’t keep me from winning the championship. I just rode bad, and it all just came down from there.

Are you ever going to show up to one of these things and say, “Hey, guys, remember me?”

(Laughs) I have a couple of times, but it’s hard. Like this weekend, I leave Thursday, and I’ll be in Houston, and every time you guys are at a supercross, I’m at a monster truck event, so it’s tough. I get one weekend off, the third weekend in March, and then the World Finals in Vegas, but I doubt I’ll make it to any supercrosses, much less a few of them. It’s fun to go, usually, like the last time I went was at Salt Lake City last year, and if I remember right, it was pretty damned good racing in both classes, but I had been to a few before that where I was ready to go because it was boring as hell. It’s weird because I look at what I do now, and it’s a whole different fan base and show and everything else, but every so many minutes, there’s something else going on down on the floor. At a supercross, you have the qualifiers, and then there’s that dead time, and it’s so weird because I’m used to everything being driven on show flow now. Nowadays, I’m looking in the stands to see their response to whatever’s going on, but never would I ever thought of doing that at a supercross. It’s just a different mindset for me now. So when I go to a supercross, I’m sitting there thinking about what can be going on down on the floor to keep these people’s attention during that dead time, whether it’s freestyle motocross, or even back in my day, I would be in the stands walking around with four or five people signing things for the fans in the stands! How much does that happen now?! (Laughs)

I’d say, almost never...

Yeah, exactly, and I remember sponsors coming to me and asking what I think about this or that, and I’d usually be down to do it, because my thought going into the place at the beginning of the night was that even if you weren’t number one in the fans’ eyes at the beginning of the night, I wanted to be at the end of the night. So it would have to be something that happened or was said, and that was always my goal, to have as many people cheering for me as possible. It’s like the one year I went to Anaheim, and I was the last guy that I felt any of those people wanted to see win – you know, because of all the California boys – and I remember going into Anaheim – the old stadium that held so many people – and thinking, “I know they want to see Ricky [Johnson] win, because he lives just up the road.” And it was pretty cool because I remember one of those races at Anaheim that I won, I had to ride the qualifier, the semi and the last chance, and then I won the main event. I had to ride all of them. Shit, by the end of that night, I felt like I had everybody in the stadium on my side, and whether it was because I had to ride every race or what, it didn’t matter. I thought it was pretty damned cool. I still think about stuff like that now because Gravedigger, Dennis Anderson is like Dale Earnhardt Jr. or Dale Earnhardt Sr. in our business. If you go to a neutral motorsports event and you put Dale Earnhardt Jr. and Dennis Anderson side by side, their autograph lines would probably be very similar. That’s just how it works. I see that on a weekly basis, and I’m thinking all the time about getting more fans, what I can do, and how I can be more creative. Usually it’s from my driving, because I don’t get a lot of opportunities to talk to the people, but at a supercross, you could say just a couple of things and turn the people around completely. It could be talking shit to some other rider, or whatever, and you could turn them around. Then, it came naturally after a while, like between me and Chicken [Jeff Matiasevich] or some of the other guys. It started to just happen.

Rick Johnson told me that he always had a goal of playing to the crowd and turning fans around.

Yup, and it was really hard to have that total package. There weren’t that many guys, even to this day, who can work the crowd and still be fast enough to win. That’s the total package.

It definitely is, and this interview is going to have people sitting for 30 minutes trying to read.

Oh well! If you think of anything else, just give me a call.

Thanks, Beast.

You’re welcome.