By Tanner Coombs

You sit down on the couch and turn on a UFC fight. The fighter from the blue corner is being introduced and you notice Joe Rogan announcing that Valentina Shevchenko is an overwhelming (-2240) favorite to beat her opponent. The fight starts, and Valentina breaks the girl’s arm in less than a minute. That’s why she was the favorite. But prior to this, a fight with very different odds occurred. The previous bout was “even money” on Draft Kings, which meant that the winner had a coin flip’s chance—an even 50% to win. If you added a third contestant to that fight, you might think that each fighter had a 33% chance at victory. Heck, add a fourth fighter and, assuming the fighters are equal, their odds would shrink to 25%. But consider this: if we add a fifth fighter to the scenario, what kind of freak would have to be in the octagon to be granted more than a 50% chance to win?

Well just a few days ago at Anaheim 1, the sports betting audience of America gave Jett Lawrence a 61.5% chance to win. The morning of the race, a leading betting platform was taking bets with Jett at a (-160) money line. [Note: The betting odds change throughout the week and were different at the time of gate drop than at the time the article was written.] With Jett's holding a 61.5% chance to win, the entire rest of the field had a 38.5% chance. Split that evenly around the other 21 riders on the gate for the main event and each had only a 2.88% chance at winning, per piece, if they shared the remainder equally. But it wasn’t equal. The next two betting favorites behind Jett, Chase Sexton and Eli Tomac, both had (+450) odds, or 18.2% chance each. Add that up and… Did we really think that Ken Roczen, Cooper Webb, Jason Anderson, Aaron Plessinger, and 16 other riders only shared a combined 2.1% chance at victory?

Keep in mind, these odds are not generated by analytics and computers. They start that way, but when players make bets accordingly, the odds shift to reflect the bets that have been placed. In other words, the types of bets people are willing to make has a massive impact on where the odds end up on race day. This is called “perceived probability,” which is derived from the group’s judgement about how likely a specific outcome is to occur. When Chase Sexton was in the lead on Saturday, he stalled his bike. Ken Roczen was very close to victory in that moment. Roczen fans around the world were pumped, and nobody would have been “astonished” if he won. But that’s not what the odds indicated: “Kickstart” Kenny was a (+3300) underdog to win on Saturday. A $100 bet would have earned a $3,400 payout if you hit when betting on Kenny, had he won! Therefore, in a 17-round supercross series, if Kenny can win once every two years, you’re breaking even if you bet on him every week.

From the two above examples, we should be able to agree that the odds were pretty crazy.

But how crazy were they, really? We recently watched Jett win 22 motos in a row, and then another few before he got hurt in June of 2024. Then he came back from injury and won the SMX World Championship. But that’s motocross, not supercross. Motos are long enough to get up and win if you fall. In SX you’re a bad start away from defeat. And yet there was Jett with a perceived 61.5% chance to win. Consider that chance over the course of a 17-round series. That puts Jett at 10.45 wins on the season. In 2024, as a 450SX rookie, Jettson was able to capture eight wins and the title. The last person to get more than 10 wins was James Stewart in 2009, and that’s the type of season the odds are projecting. Furthermore, that’s being projected even when you’ve got Eli Tomac, Chase Sexton, Cooper Webb, and Jason Anderson on the line, all of whom have been supercross champs in the past.

Let’s say it’s Saturday morning and you’ve got $100 to bet on Anaheim 1. You have options. You could bet $100 on Jett Lawrence (-160). If he wins, you get $162.50, for a profit of $62.50. Or you could take $50 and put it on Eli (+450) and take $50 and put it on Chase Sexton (+500) [Hey look! It moved], knowing that only one could win. When Chase won, you would have gained $300, then lost $50 on the Tomac bet, netting $250 for your $100 bet. Was it really that much more likely that Jett would win than either Eli or Chase?

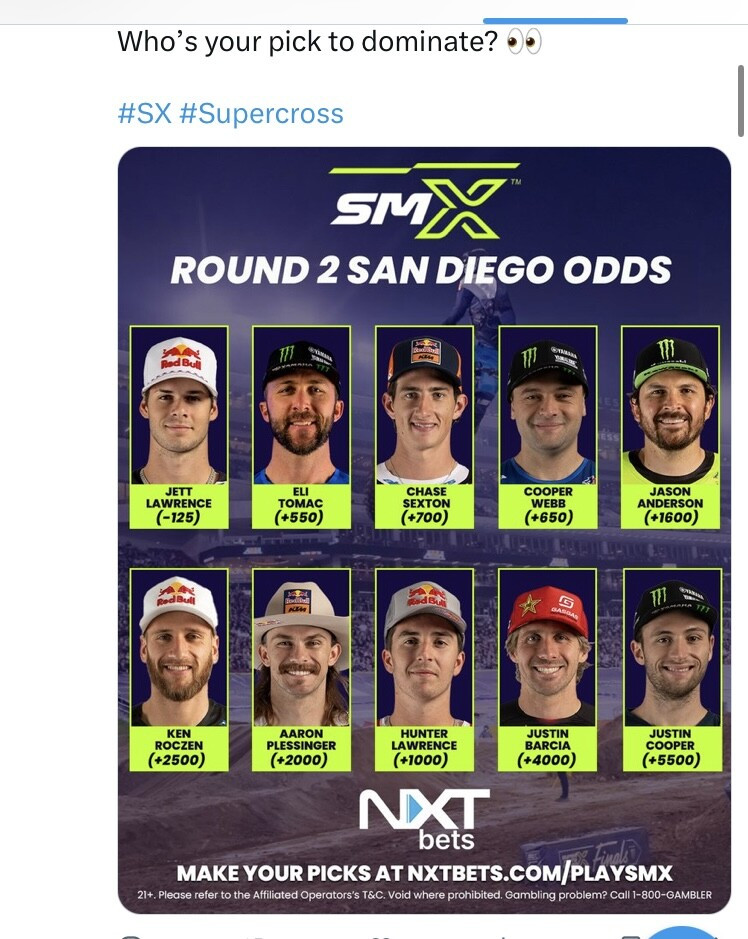

On January 14th, NXTbets posted the odds for Round 2 in San Diego, which happens today. Those odds opened with Jett Lawrence as a favorite again—albeit a lighter favorite—at (-125), but with the guy who just won at Anaheim 1, Chase Sexton, all the way at (+700). Ken Roczen took second place at Anaheim 1, and he still opened at (+2500), which is a 3.8% chance to win. Remember, Chase made the mistake while in the lead and Kenny was right behind him. Jason Anderson rounded out the podium and is at (+1600), which is only slightly better than the odds from before A1, but still better than Kenny. Why would that be?

Related: San Diego Supercross Betting Odds Are Live: Jett Lawrence Still Favorite Despite Struggles at A1

Fast forward to today, I’m looking at Bet365 (simply because it’s the easiest to check from my phone here in my home state) and the odds have moved quite a bit. Jett is currently at (-120), which is only 54.5%, down from last week, but still “more likely than not” even though you have a white-hot Chase Sexton to contend with, and Eli Tomac who, for all we know, was one slip and fall from running away with an early lead. He was in last right next to Jett and moved through the pack much more efficiently. Sexton is now at (+300) and Eli at (+350). Their odds have both improved over where they opened, but not by huge margins.

Lastly and perhaps most curiously of all, we have Ken Roczen and Jason Anderson at (+2500) and (+3300), respectively. Even with that second-place finish, Kenny hasn’t moved from where he opened at all, and El Hombre has actually moved down on the perceived probability, meaning we didn’t have many takers at the (+1500) where Anderson opened. In sum, the movement of the betting odds offer an interesting insight into what the fans are thinking, because this is their first collective try at putting their money where their mouths are.