This text originally appeared in the 2024 THOR Mini O's event program.

The sport of motocross racing is always evolving. Whether it’s the motorcycles, riding technique, track design, training programs, or the industry itself, motocross is in constant flux. Born 100 years ago (March 29, 1924, to be exact) in England at an event called the Royal Scott Trial the sport has gone from a modest gathering of off-road enthusiasts on modified street bikes to the massive global sport it is today. And with a record 6,000-plus entries in 2023 the THOR Mini O’s has grown into the single biggest stand-alone event in the entire dirt bike world. And this year’s 53rd Annual Mini O’s promises to be an even bigger race. With a nod to the many instructors that are part of On Track School, we thought this would be a good time for a motocross history lesson. So, let’s turn the clock back—but not all the way back to 1924—for a look at how motocross in general, and the Mini O’s in particular, have evolved over the years.

Motocross first started gaining traction in America in the mid-1960s, when an imaginative California businessman named Edison Dye came up with a unique way to sell the public on the off-road motorcycles he was importing called Husqvarnas. Dye invited the reigning Motocross World Champion, Sweden’s own Torsten Hallman, to race the lightweight two-stroke Husqvarna against Americans who were still racing converted Triumph, BSA, and even Harley-Davidson scramblers. The Inter-Am Series, as Dye called it, was a smash hit for him, as Hallman pretty much dominated the Americans. So, in 1967 Dye expanded the series and invited more Europeans over, including a young Roger De Coster. Hallman also returned, bringing some of the motocross-specific riding gear only found in Europe at the time to the states to sell. In doing so he basically invented what we now know as the motocross aftermarket industry. He called his gear Torsten Hallman Original Racewear, or what we now know as THOR, the title sponsor of the Mini O’s.

Fast forward to 1972, which was a very important one in the evolution of motocross. The movie On Any Sunday was in theaters, introducing motorcycle racing to a brand-new audience. The AMA Pro Motocross Championship was born, and the first Superbowl of Motocross—what we now know as supercross—took place inside the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Honda began the process of building their ground-breaking Honda Elsinore CR250 and, maybe even more importantly, their XR75 minicycle.

It was in November of ’72 that a Florida motocross promoter named Pat Ray came up with the idea of hosting a big minicycle race over Thanksgiving weekend. His Jacksonville racetrack, North Florida Raceway, had a small flat track that ran alongside its motocross track as well as the surrounding woods. Ray wanted this new event to be a multi-discipline “Olympiad” with flat track, hare scrambles, and motocross, and then crown the best all-around minicycle racers. He called this mashup the Florida Winter Nationals. It would be the first “national-caliber” event on the east coast for kids, similar to what the old World Mini Grand Prix was for west coast riders.

The new race attracted two of the best young riders in the country and who helped define and advance minicycle racing in the early seventies, California’s “Flying Freckle” Jeff Ward and Tennessee’s Gene McCay. Ward would be riding the brand-new Honda XR75 while McCay rode a Honda SL-70 trail bike converted into a race bike. Heavy rain made the Winter Nationals a true test of all-around skill, and both Ward and McCay would win motos and classes from one another, and the first real rivalry in U.S. minicycle racing was born. By all accounts the event was a success.

One year later a sanction was added by the California-based National Minicycle Association, which helped draw more west coast riders than just Ward. Mike Brown (the one from California, not Tennessee), Paul Denis, Lance Moorewood, Jim “Hollywood” Holley, and more caravanned across the country with Honda’s Ward—the first-ever minicycle rider to sign a factory contract—leading the way. Ward would win the 80cc class but come up short in the 100cc class to Indiana’s Kenny “The Missile” Blissett, who rode a Steen Allsport.

The Florida Winter Nationals grew quickly from there, and within a few years the race was too big for North Florida Speedway. Another Florida promoter, St. Petersburg-based Bill West, took over the event from Ray and moved it further south to a bigger facility in Homosassa Springs called Chicken Farm Raceway, just above Tampa. The event still called for a hare scrambles, then flat track and TT races at nearby Ocala, and finally the motocross finals. West also dropped the NMA sanction and went with the Ohio-based American Motorcyclists Association (AMA) and he rebranded the entire event, calling it the Mini Olympiad, later shorthanded to Mini O’s. The ’77 race attracted 700 young riders, with standouts like Florida’s own Mark Murphy and Todd Hempstead.

Bill West, by the way, was not just an amateur motocross promoter. He was also the co-founder (along with Russ Coe) of the Florida Winter-AMA Series, which at the time was every bit as big as the AMA Pro Motocross Championship. West’s company, known as Supersports at the time, was also involved in hosting outdoor nationals, Trans-AMA races, and the Atlanta Supercross, which started in 1977. From there he would go on to organize countless stadium events all over the country. He eventually sold the supercross portion of his business in 1998, and the THOR Mini O’s would be sold to Wyn Kern’s Unlimited Sports MX, organizer of the event to this day. Bill West remained a hugely influential figure in the sport and industry for the rest of his life. Sadly, he passed away in July of this year at the age of 88.

By the early ’80s the Mini O’s was attracting the best young riders from all over the country. The amateur motocross industry was growing, especially after Kawasaki began its game-changing youth and amateur support program known as Team Green in 1982. The Mini O’s had expanded its class structure by that point to include more and more adult motorcycle classes, as the race had become a Thanksgiving tradition for many moto families. The tradition of having a huge feast when moms would cook up turkeys bought by either the promoter or race sponsors become a major component of the whole Mini O’s experience, which continued to grow.

It was also soon time for another move, and West took the event to its current home, Gatorback Cycle Park, though the dirt track racing would still take place in Ocala. The new location also saw the addition of a supercross track, and that discipline would soon replace dirt track in the Mini O’s format.

The stature of the event grew, based in large part on the east-versus-west rivalry that was growing throughout the sport. While most of the fast pros were traditionally from California, a paradigm shift was starting to take place. The Michigan Mafia was soon challenging the Golden State and the Sunshine State for supremacy, at least in terms of youth and amateur racing, and the Mini O’s were ground zero for these battles. Into this fray rode a kid from North Carolina named Damon Bradshaw, soon to be known as “the Beast from the East.” With his skill and competitiveness Bradshaw became something of a sensation, and he used the Mini O’s every November to put it all on display, even after he turned pro in 1988, when he shocked the world by winning the Tokyo Supercross in Japan, beating superstars like Rick Johnson, Jeff Ward, Ron Lechien, and Johnny O’Mara. That following weekend Bradshaw was back on the starting gate for the motocross portion of what was by that point the 17th Annual Mini O’s.

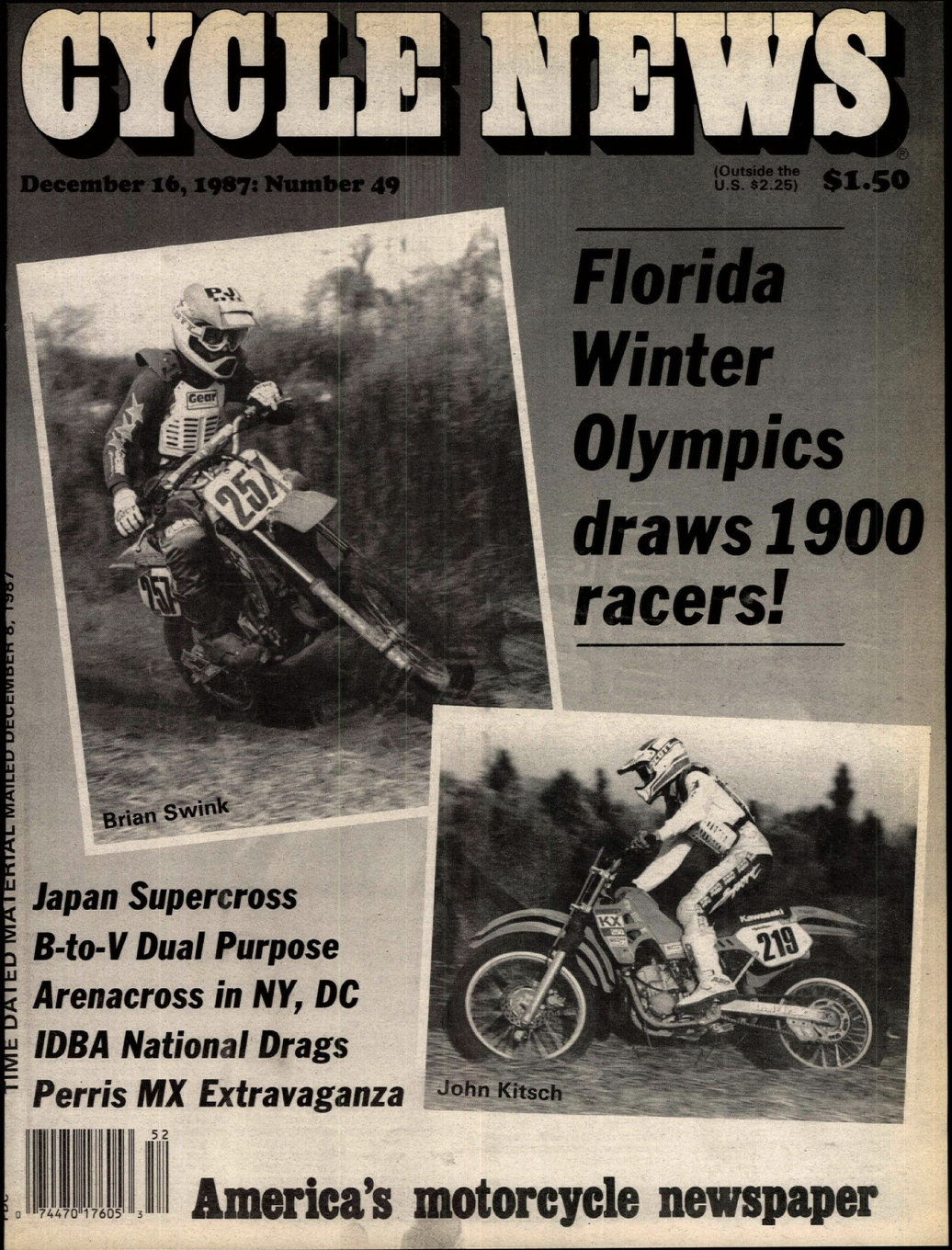

Other future superstars to come out of the Mini O’s during this time were Georgia’s Ezra Lusk, Michigan’s Brian Swink, Oklahoma’s Robbie Reynard, and Louisiana’s Kevin Windham. And Florida itself has produced many of the best riders of all time, including Havana’s Ricky Carmichael and Haines City’s James Stewart, both of whom first came on the national map with their successes in the Mini O’s every November. Same goes for future WMX great Jessica Patterson and Ashley Fiolek, both of whom hailed from Florida and were staples of the Mini O’s. The event continued to grow, surpassing the World Mini GP and the NMA Grand National in both size and importance. A casualty of this growth was the off-road portion of the event, as Gatorback Cycle Park would be filled to the brim with campers, motorhomes, box vans and trailers, making it difficult to continue to have a meaningful off-road competition.

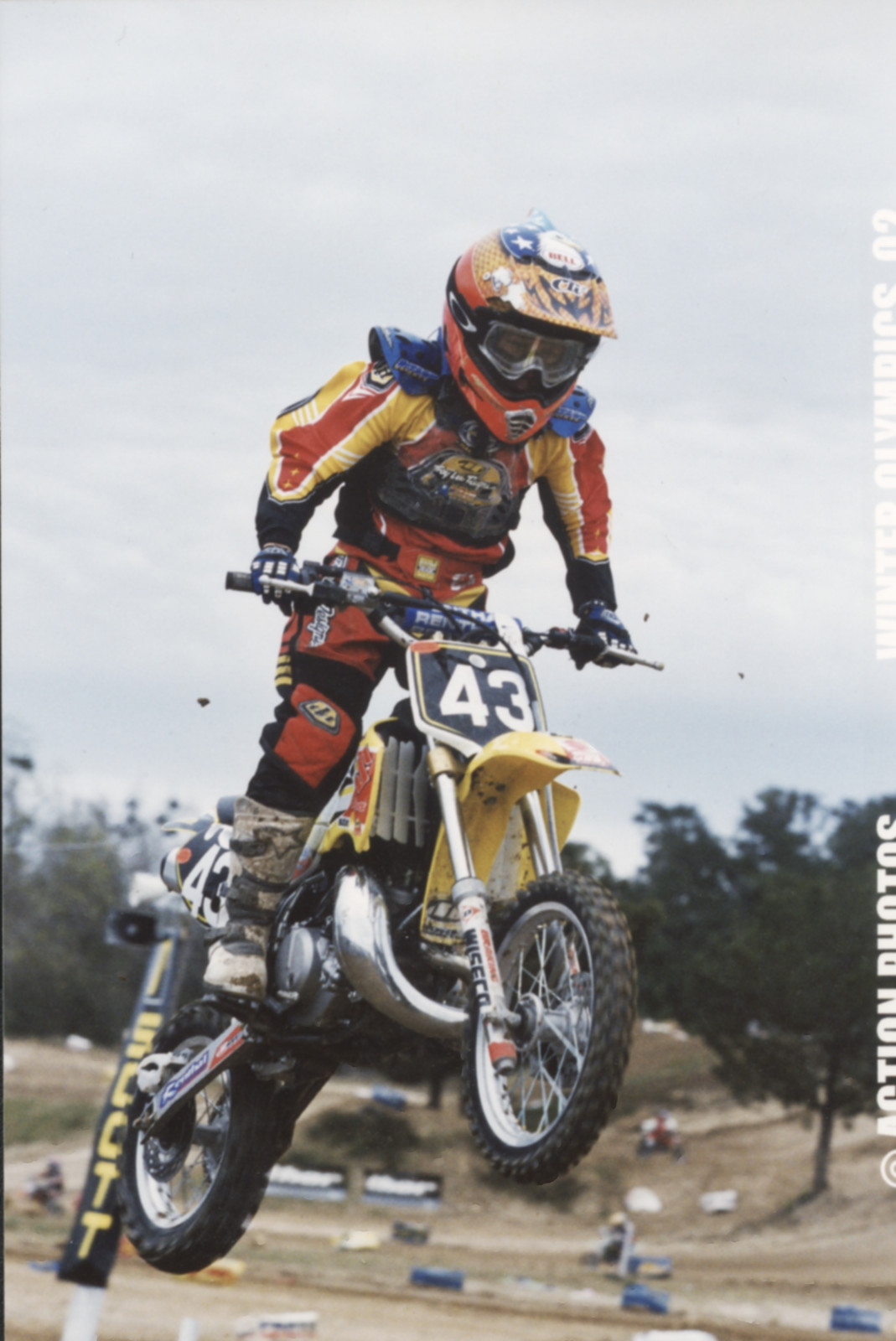

One of the trademarks of the event is the fact that it serves as both the last big event of one calendar year, as well as the first big preview of what’s to come. This is the time of year that young riders transition from 51cc to 65cc, 85cc to Super Minis and 125s, and ultimately 250 and 450 motorcycles. As a result, the THOR Mini O’s have been a huge platform in the development of pretty much every top professional in the sport over the last couple of generations, including Minnesota’s Ryan Dungey, Washington’s Ryan Villopoto, Colorado’s Eli Tomac, North Carolina’s Cooper Webb, and New Mexico’s Jason Anderson, Illinois’ Chase Sexton, and even Australia’s Jett Lawrence, all of whom have gone on to become the AMA 450 Supercross Champion (and Jett Lawrence and fellow Mini O’s graduate Haiden Deegan are also the sport’s first two SuperMotocross World Champions).

This week more than 6,000 riders are expected to again sign up to compete in what’s now the 53rd Annual THOR Mini O’s. Over the course of an entire week, they will be competing in the supercross and motocross portions of the event. In a further nod to the evolution of the sport every moto will stream live and free on racertv.com. Who will be the next young future superstars to emerge from the biggest and oldest amateur motocross event in the entire sport?

Good luck, everyone, and enjoy your families and friends, enjoy a great and safe week of racing here at the 53rd annual THOR Mini O’s. Class dismissed.