On the last day of each year, we look forward to a brand new season, as well as a look back at some of the friends and fellow riders and racing enthusiasts we lost along the way. With a nod to The New York Times’ annual requiem, here are just a few of the lives they led…

If you dive into the early records of American motocross you will find the name Robert Harris in the results. The New Yorker was one of the fastest racers in the country, with the credentials to prove it. In the very first outdoor national—at Georgia’s Road Atlanta on April 16, 1972—he finished seventh aboard a Spanish-built Bultaco. At the second national, held outside of Memphis, Bob claimed second overall, a result he would match in future national races but never better. Harris was on the circuit before pro motocross became the big business it is now, his pro career finished by 1976. But his love of motorcycling led him to continue to ride and race locally, while also teaching motocross to young riders who wanted to learn from a master. Harris also held the distinction of being the man to try to help sort out the American-made Rokon 340 automatic “Cobra” motocross bike—one of the oddest bikes ever made for motocross. But that misadventure went right along with Harris’ favorite saying: “When in doubt, gas it out!” Harris passed away unexpectedly at his home in Windsor, New York, survived by his wife, Diane; children, Robert and Billie Sue; and ten grandchildren.

Robert Harris.

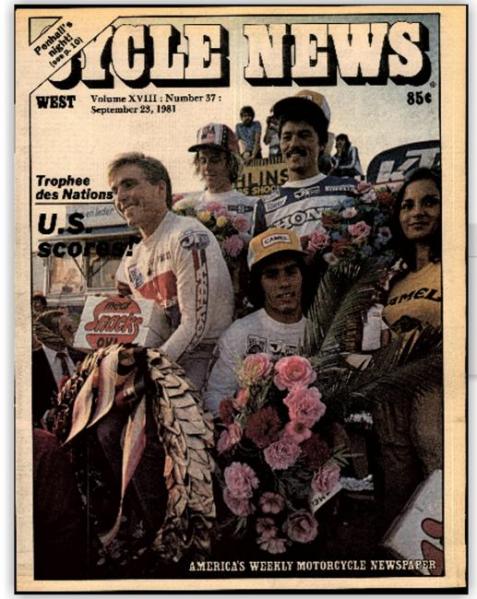

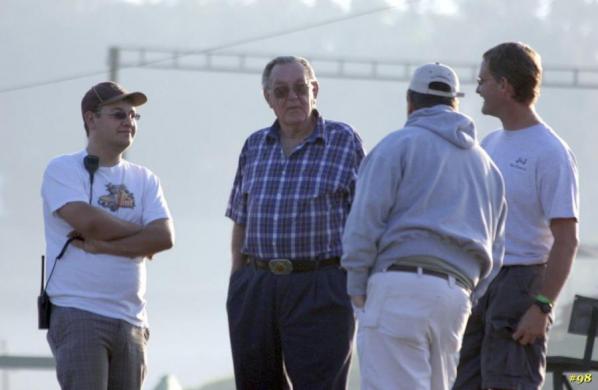

For more than thirty years, Henny Ray Abrams was considered one of the most respected and talented journalists in all of motorcycle racing. He was a real newsman, not a fan or enthusiast who wrote or shot photos of the sport he liked, proven by his longtime standing as an Associated Press reporter and photographer. He lived in New York City, far away from the California motorcycle industry, yet his presence was felt every day—particularly in road racing circles, which became his beat. But for a time, Henny was also a motocross watcher, and he was the man who shot the iconic Cycle News cover of Team USA after their shocking win at the 1981 Trophee and Motocross des Nations. Abrams regularly took on the road racing establishment, especially the AMA and Daytona Motorsports Group in the years after the sale of AMA Pro Racing. Henny used the bully pulpit of his weekly Cycle News column to lay out his criticism, much to the dismay of the powers that be—and much of the delight of his regular readers.

When motorcyclists die while riding or racing, we take solace in saying “he died doing what he loved.” In Henny’s case, he was in his Manhattan apartment, working at his computer on a Cycle News story, when he suffered a fatal heart attack. Henny Ray Abrams died doing what he loved.

Henny Ray Abrams photo.

Bill Nilsson was a hard man of motocross long before the sport took hold here in the States. He was the first 500cc FIM World Champion, winning the inaugural series in 1957, at a time when motocross was still called “scrambles” here. Hailing from Sweden, he was the father of the motocross world, first in a long line of champions to roll out of the Scandinavian country at the top of Europe. He would finish first or second in the championship every time for the next five years, and his 1960 world title—won riding a four-stroke Husqvarna that weighed 322 pounds—marked the first world title for the brand. Nilsson would also venture into enduro racing, as the motocross seasons that far north were shortened by the cold and snow. Nilsson would be followed in the long blue-and-gold line of Swedish motocross heroes by Torsten Hallman, Sten Lundin, Rolf Tibblin, Bengt Aberg, Ake Jonsson, Hakan Andersson, Hakan Carlqvist, Jorgen Nilsson.… So strong were the Swedes back then that in 1960, when Nilsson won his second world title, the overall podium was rounded out by Lundin and Tibblin. All three rode Swedish-made motorcycles (Husqvarna for Nilsson and Tibblin, Monark for Lundin). Bill Nilsson passed on August 13, 2013. He was 80 years old.

Bill Nilsson.

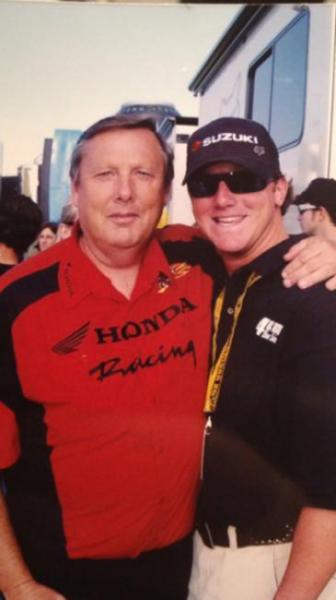

For eight years, Mark Hough had his dream job: driving the Team Honda motocross semi around the country, following the pro racing tour. Whether you were an industry friend looking for a cup of coffee on race morning or a kid hoping to get a poster or sticker from the team, Mark had time for everyone. Hailing from Maryland, he cared for the Honda rig like it was his own, and he seemed to relish every day at the races or on the road as another adventure. A few years ago he figured it was time to hand the keys to another driver and head back home to Gaithersburg, Maryland, where he was restoring a Kenworth tractor-trailer. In February he decided to make the drive south to the Atlanta Supercross to visit his old team and racing friends, but he never made it to the stadium. The night before the race, he suffered what appeared to be a heart attack. Mark Hough was 53 years old.

Mark Hough (left).

Julie Grigg Rodgers enjoyed a rich family life, surrounded by motorcycling. She was at the side of her husband, Dave Rodgers, as he worked in the motocross industry—Julie met Dave at a racetrack when she was 16 years old. They immediately hit it off, eventually married, and for the next forty years were part of the fabric of the motorcycle racing industry. The Rodgers family had six children, and all six—plus many grandchildren, and of course her husband Dave—were with Julie when her six-year battle with breast cancer ended on May 31, 2013.

Julie Grigg Rodgers.

Few people in America may know the name Jean-Claude Olivier, but in France he was a giant, an iconic motorcycle industry presence who touched many lives and careers in a life spent on two wheels. He was a racer as well as a worker, and one of his biggest successes was a second overall finish in the brutal Paris-Dakar Rally across Africa. As the man in charge of Sonauto (Yamaha’s early French importer) and later Yamaha Motor France, he was vital in the careers of such French luminaries as Jacky Vimond (the first Frenchman to win an FIM World Motocross Championship), Stephane Peterhansel (the rally king), road racer Patrick Pons, and more. Olivier was called “Monsieur Le President” not only because of his job, but the commanding presence he had for two generations of French motorcyclists. He retired in 2010 after forty-five years in the industry. Sadly, his life ended on four wheels, not two—he perished in an automobile accident with a tractor-trailer that had lost control on the highway. He was 67 years old.

Jean-Claude Olivier.

Eigo Sato was a freestyle jumper who was respected worldwide for his kindness as well as his talent. Sato was proud of his homeland of Japan, and when the earthquake and tsunami hit two years ago, he helped pull together fundraising events to help his devastated homeland. He was also a family man, with a wife and two young children. It was his drive to provide for them, as well as to be the very best jumper in the world, that led him to that cruelest of FMX tricks, the backflip, which led to his tragic death last spring. Sato was practicing for the upcoming Red Bull X-Fighters in Japan when he under-rotated on a flip and crashed. The news of the 34-year-old’s death devastated his friends and fans all over the world. "RIP Eigo Sato," wrote André Villa in an Instagram post. "I love you. Always have, always will. You been like a big brother to me and I have always looked up to you. Nicest person in the pit, toughest man on the track. I can not believe you are gone. Thank you for everything you gave me and the people around you. For what you have done and who you have been, you will live forever. #EIGO4ever."

Here is a tribute to Eigo Sato.

Eigo Sato.

David L. Watson did not race motorcycles, nor did he necessarily care much about them—at least not early in his life. Then he had a son named Matt, and Mr. Watson become something familiar to many in motocross: a father with a son who wanted to race so badly that he had no choice but to get involved—then came to love it. Watson spotted a used minicycle for sale in a neighbor’s yard and snatched it up as a Christmas present for Matt. What followed was a lifetime around the sport, as the boy raced for years, then went to work managing various local motorcycle dealerships. Mr. Watson stayed interested in dirt bikes long after his son moved out and started his own family, because it was his grandchildren who were soon getting into the sport. When David Watson died in January, he was 72 years old; he’s survived by Diane, his wife of fifty years.

Steve Bruhn was a rocket scientist—literally. He was a propulsion engineer in aeronautics who worked for various airlines, shipping companies, and even NASA. But he will forever be remembered in the motocross world as TFS, The Factory Spectator. Bruhn raced back in the day growing up in Texas, then began his career in engineering. At some point he picked up a digital camera (something new that was frowned on by traditional film photographers) and began shooting races. He soon became the first “photo hound” to bring high-quality digital photography to this sport. Because he worked for the airlines, TFS could travel to the races free—hence the nickname “Factory Spectator”—and he soon began shooting for publications like Cycle News and Racer X Illustrated. Bruhn was also a constant presence on the message boards, helping the influence of the new medium rapidly expand. His debate approach and sheer knowledge made him a force to be reckoned with: “Seat Bounce Theory, anyone?”

Bruhn soon became so busy with race reporting and his online work that he quit engineering, bought a motor home, and began traveling the circuit in what came to be called the Ego Mobile, complete with a cartoon caricature of himself plastered on the sides. While he had his less serious side, Steve’s work cut a deep path through the new medium of the internet that many have since followed.

Bruhn also had some complicated health issues that made things less than comfortable for him on a day-to-day basis. Late in his life, as he dealt with a rapidly changing landscape in both media and the business of motocross, not to mention his own declining health, he appeared to be trying to get back to his roots. He returned to the business of rocket science (engine propulsion, actually), quit the races, and parked the Ego Mobile in a campground near where he worked in Alabama. Then his heart gave out. Steve Bruhn died in a Memphis hospital on May 7. He was 52 years old.

Steve Bruhn.

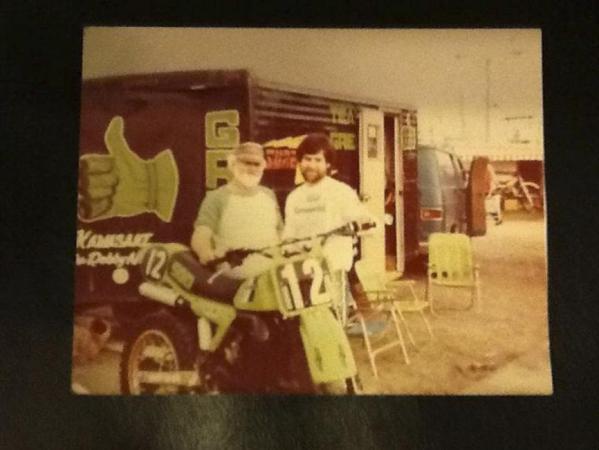

Back in the early days of Team Green and big-time amateur motocross, Robert Neeley was Kawasaki’s go-to guy for the vet classes at Loretta Lynn’s and other big amateur races. In fact, the South Carolinian won six vet-class titles at the ranch, all but one on green bikes. Alongside him for all of those wins, plus many more along the way, was his father, Robert C. Neeley Sr., even though his son the racer was by then a middle-aged man. So it was sad irony when the son was away at the races in June—following his own grandson Cole Mattison at the Snowshoe GNCC in West Virginia—when Neeley passed at the age of 82. As one friend said of the late Mr. Neeley, “I will always remember him as a class act and one who dearly loved his son and our sport."

Robert C. Neeley Sr. and Jr.

In the early days of motorcycle jumping it was distance, not freestyle tricks, that caught the attention of thrill-seekers. Daredevils like Evel Knievel, Bobby Gill, Bob Pleso, and Super Joe Einhorn were so popular that they often found their jumps making national news, showing up on ABC’s Wide World of Sports or some other mainstream network show. In the nineties and the first part of this millennium, FMX took hold and the popularity of distance jumping seemed to wane. But recent years have seen a renaissance of sorts, with riders like Robbie Maddison, Ryan Capes, Trigger Gumm, and the notorious Seth Enslow using modern equipment to push the records. In fact, the current record for distance jumping is 425 feet, set by Alex Harvill on a 450cc motorcycle.

Australia’s Tyrone Gilks wanted to break all of those records. He had been pushing his own limits for years, growing up and moving up to bigger bikes and setting age and displacement records along the way. But four years ago he decided to venture more into contest FMX, hoping to make it in the X Games or on the Red Bull X-Fighters circuit. Last year, inspired by Harvill’s record, he returned to the distance game. Gilks was planning to jump 330 feet—a jump he called Operation 330—when he came up short on a practice launch at some 280 feet at Australia’s Maitland Showgrounds. He cased the landing, breaking his bike in half. He was rushed to a nearby hospital but died hours later. He was 19 years old. His tragic death sent shockwaves through the action-sports world; the Facebook page “R.I.P. Tyrone Gilks” has grown to nearly 45,000 followers.

Tyrone Gilks.

Lamont Perkins never raced motocross or even motorcycles. But if you’ve been to Loretta Lynn’s Ranch in the past half-dozen or so years, you might recognize him as the man in charge of all the trash the week of the big motocross race. Perkins was a career soldier in the U.S. Army, and when he retired he returned to Waverly, Tennessee, where he lived with his family. He came out to the ranch one day a few years back looking for work and ended up on the trash wagon. Pretty soon he had his own part-time business, organizing a crew of local kids and friends and making the task seem like the most important work of all. Lamont was both strong and friendly, making friends easily with many of the racers and their families at the ranch, even while hoisting their garbage bags in and out of wagons. He even organized a recycling unit at the request of some ranch visitors. Sadly, Perkins took ill last spring and was diagnosed with ALS, a cruelly debilitating sickness often called Lou Gehrig’s Disease. Six weeks later he was gone.

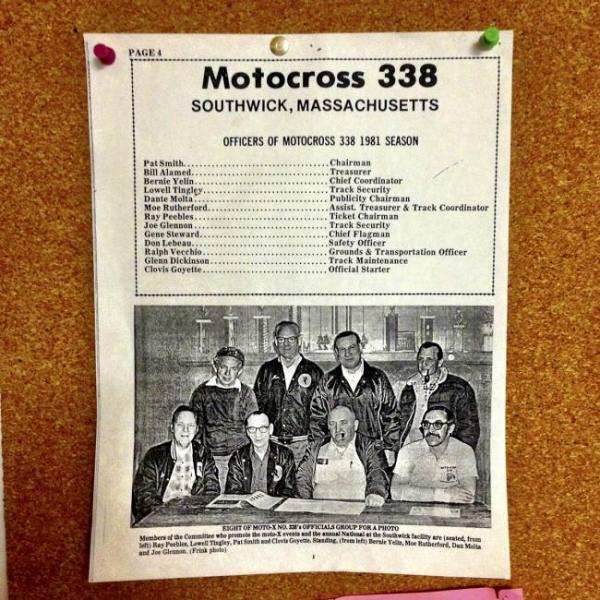

Clovis Goyette was a well-known presence at the Southwick MX-338 racetrack. He was one of the founders of the Massachusetts motocross track, which dates back to the early 1970s. A veteran of the U.S. Air Force, Goyette was a proponent of the idea of putting a motocross track on the American Legion Post 338’s grounds, hoping it would give local kids a place to ride and hang out, and also help raise money for the cancer-fighting Jimmy Fund. As a result, he was a founding member of MX-338 and could often be found working on the infield or driving tractors around the facility. Other times he could be found holding court inside the Legion hall next to the racetrack, ready to bench race about anything from Jimmy Ellis to John Dowd, four-strokes to backward-falling starting gates. Clovis passed suddenly at home in September. He was 69 years old.

Clovis Goyette (bottom right).

Kenny Clayton went by the screen name “OldX” on the message boards and forums he sometimes frequented—he was a charter member of KTMTalk. He lived his life on the West Coast trails and in the garage, a core moto man for decades. His enthusiasm for the simple pleasures of riding never left him, even with chronic knee pain, and he frequently made riding trips to the Cascade Mountains and the Mojave Desert. Clayton was also into long-distance swimming, scuba diving, bicycling, and skiing, living an active life after retiring from a career as a home builder on Camano Island in Washington with his wife of nearly sixty years, Gayle. According to his niece, who posted news on KTMTalk, “Kenny loved to ride and lived to ride. He raced for so many years, he raced in the grandfather league.” She also reported that her uncle bought himself a new bike just last year—at the age of 76! Happy trails, OldX.

Kenny Clayton.

There’s been a resurgence lately in Minnesota motocross, led by superstar Ryan Dungey, the Martin brothers, the thriving Spring Creek National, and even the feel-good story of summer, Jerry Robin and his 1985 CR250. Eric Sauer was there to see it all happen. After graduating from high school, he worked his way into the motorcycle industry at Two Brothers Honda next door in Wisconsin, and also wrenching for Heath Voss and the Martin family. He started his own hop-up shop ESR (Eric Sauer Racing), customizing bikes for performance and speed. Sadly, Sauer suffered some kind of stroke in November after undergoing back surgery and passed away at the age of 33, leaving behind his wife, Bethany, and their two daughters, Alexis and Kaitlyn. Said his uncle, “His life was too short but he was true-blue motocross!”

Eric Sauer.

It’s difficult to make sense of an unexpected tragedy like the one that took the life of off-road hero Kurt Caselli in November. The KTM factory rider was competing in the Baja 1000 in Mexico and was well out front when he crashed at high speed near the 792-mile mark. No one saw what happened, and after some initial confusion, it was reported by his team that Caselli had struck some kind of animal. The news hit the motorcycle industry hard: Caselli was one of the all-time good guys, an incredibly versatile, world-class racer and a very good man. His death brought the entire motorcycling world to pay their respects; a memorial ride at Glen Helen Raceway brought out hundreds of friends, fans, and competitors.

A few weeks after the accident, KTM North America president Jon-Erik Burleson posted a poignant story about the kind of person Kurt Caselli was:

“Been having a tough time to find the words and photo I wanted to share. Kurt was such a great person and leader on our team its hard to put into words all who he was. He was a good friend and part of our family. When Kurt came back from Dakar in January we went out to lunch to celebrate and talk about all he had accomplished in his rookie year. After me carrying on for too long about how awesome it was, Kurt interrupted me to ask if he was allowed to volunteer to work one of our KJSC events. He wanted to spend time with the kids and just give back to a sport that gave him so much. I still don't know the best words to describe how much I miss him, but this shot represents so many things we all loved about Kurt. I know he is up in Heaven riding with his Dad, but I sure wish he was still here to ride with us tomorrow. He will always be a person I will look up to. #KJSC #Motorcyclist #Legend #Friend #KC66”

Kurt Caselli.

ESPN had reporter Alyssa Roenigk embedded with Caselli’s team during the fateful race. Her feature story detailing the situation is an exceptional piece of reporting.

Just hours after the confusing news about Caselli’s death and its circumstances reached the internet, a similar accident took place in the middle of Ohio. Ryan Longstreth was riding home from work at Cycra Racing, where he was the company’s brand manager, on a motorcycle when he struck a deer. Longstreth had been involved in motorcycle racing, as well as Cycra, for pretty much his entire adult life. The accident also caused some initial confusion, as his helmet was off when help arrived on the scene, leaving police to at first suggest he was not wearing one. It was later determined that he was indeed wearing the helmet, but it came off in the impact of the collision with the animal.

Longstreth was a frequent presence at both professional and amateur races, with a big smile and a friendly word for everyone. His accident brought what seemed like the entire Ohio motorcycling community out to pay their respects to a good man gone way too soon. Ryan is survived by his wife of twenty years, Harmony, and their daughter, Morgan, a college student. He was 38 years old.

Ryan Longstreth.

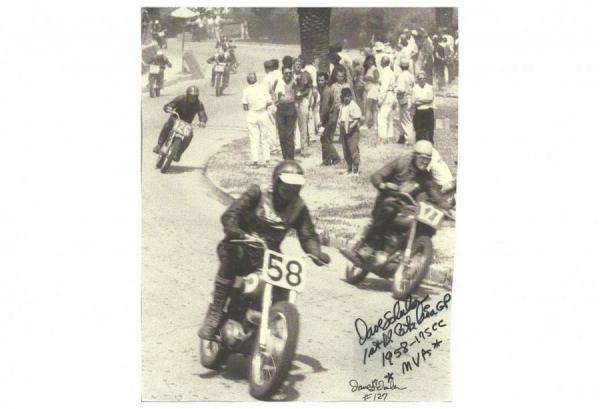

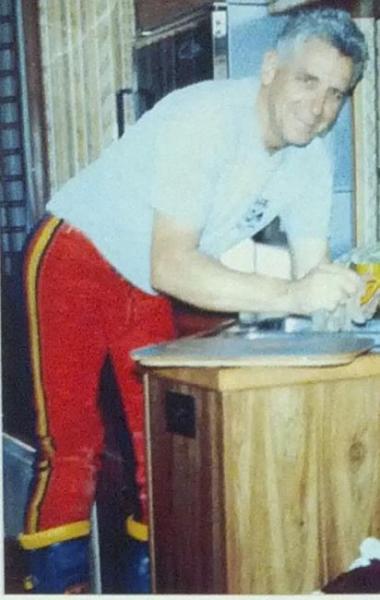

In July, David Schuler passed peacefully at his home at the age of 80. He was born in Ohio, moved to California, served in the U.S. Army in Germany, and enjoyed a lifetime of motorcycling. Schuler was a lifetime charter member in the Hilltoppers Motorcycle Club of Long Beach, California, and was also inducted into the TrailBlazers Racing Hall of Fame. While working at Quaker State, he sponsored numerous desert and speedway racers with Quaker State products. He was also the finish-line flagger for many NMA events during the seventies. Schuler’s greatest accomplishment as a competitor was winning the 1958 Catalina Grand Prix on an MV Augusta in the 175cc class. He was one of the last surviving Catalina GP Champions and was in attendance when the race returned briefly in 2010.

David Schuler.

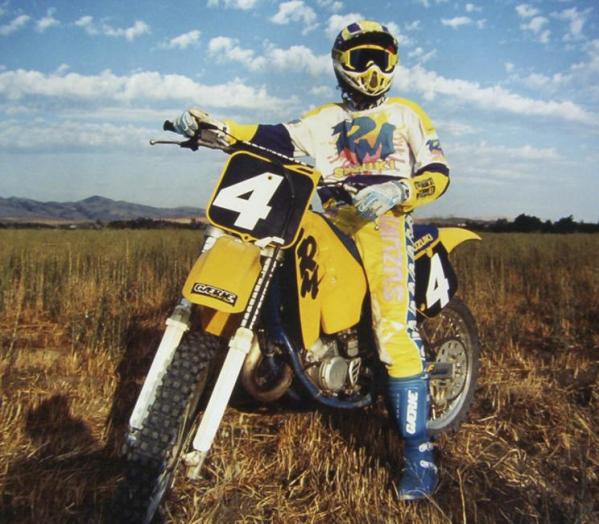

It’s almost impossible to become a successful racer without solid support from your family, particularly a parent. Buddy Antunez, the greatest Arenacross rider of all time, had that: His father, Big Buddy Antunez, was a well known and highly respected presence on the SoCal motocross scene as his son was coming up through the ranks as a factory minicycle racer for R&D Suzuki. Big Buddy not only helped guide his son to success, but many other kids as well. Antunez Jr. would eventually turn pro and enjoy some success as an SX/MX racer, but he really came into his own on the Arenacross tour, where he ruled for nearly a decade. Big Buddy taught little Buddy very well.

Steve Cox was one of the aspiring young racers whose life was touched by Big Buddy Antunez. He wrote a remembrance of Big Buddy and posted it on Vital MX.

Big Buddy Antunez.

Taryn Hawk was a funny, cool, charismatic, and downright sweet guy. He worked for Sole Technology for twelve years, most recently traveling to all of the outdoor nationals and helping man the Etnies bus while sporting blue-jean overalls and a white T-shirt, handing out those vuvuzela horns, and enjoying the chance to talk to so many people across the country.

Hawk was at a trade show in Long Beach in July when he and good friend and travel partner Joey Daroza packed up their booth and left on their Harley-Davidson street bikes. Moments later, at approximately 8:45 in the evening, local restaurant owner Nicholas Limer, 68, westbound of 2nd Street, made an unsafe left turn across traffic in his SUV. Hawk and Daroza were riding east on 2nd, two lanes over. Limer would later tell police and friends that he never saw the motorcycle riders, which smashed into his vehicle. Daroza was taken to a nearby hospital with minor injuries. Hawk died at the scene; he was 35 years old.

A couple weeks after the accident, a paddleout was organized in Taryn’s honor at Huntington State Beach, followed by a tribute lunch at Taryn’s favorite restaurant, Cook’s Corner in Trabuco Canyon. The Hawk family said in a statement that “Taryn was our family’s heart.”

Taryn Hawk.

There was a time in Southern California in the 1970s when one might go to a local race and see a whole bunch of kids out there flying around with the name “LUTZ” on the backs of their jerseys. They were Randy, Lori, Debbie, and Steve Lutz, the children of Larry Lutz. Aside from motocross, Lutz loved race cars, model cars, boating, and the responsibility of trying to help others—he was a fireman in Anaheim for thirty years, retiring in 1986 as a captain for the City of Anaheim. When he passed recently at the age of 80, he was survived by his wife of fifty-nine years, Marilyn Lewis, and all four of those racing children, one of whom is WMX pioneer Debbie Matthews.

Larry Lutz.

One day in 1969, in a small shop in England, Andrew Renshaw and his good friend Harry Rosenthal decided to start their own metal-shaping company, using a tube-bending machine to craft motorcycle parts. They combined their last names to come up with the company’s moniker: Renthal. The first handlebars they made were a prototype that Rosenthal made for his trials bike. According to Wikipedia, it was crafted from H14 aircraft aluminum that was left over from World War II. Over the years, the two would work together to establish the brand and its products, which soon became famous in the motorcycling world—particularly in motocross, where Renthal products have accounted for hundreds of national and world championships and thousands of race wins. In recent years, Renshaw found himself enjoying much of his time working on his 200-acre farm. Cancer claimed his life on October 27; Renshaw was 73 years old.

Andrew Renshaw.

Jake “Turtle” Wikoff hailed from the Hollister, California, area, home to the old Grand Prix track. He was well-liked, a great rider, a respected coach, and one of the OG freestylers, appearing in videos including Moto XXX, Disturbing the Peace, and The 1000 Mile Jump. Jake was sponsored by LBZ, a brand affiliated with those halcyon days of freestyle motcross. He was a motocross man through and through—he even had a son named Ryder, not to mention three daughters named Alycin, Skylar, and Chloe Wikoff. He passed away after an automobile accident on a rural road outside Hollister. He was 37 years old.

Jake “Turtle” Wikoff.

In the November 2013 issue of Racer X Illustrated we presented a feature article by Fran Kuhn about the work that Al Holley did on minicycles back in the day, particularly the vaunted XR75s he made for his son Jim. It was an incredible piece, detailing what was effectively the birth of big-time minicycle racing in this country during the motorcycling boom of the seventies. If that was all Al Holley ever did it would have left him a fine legacy in this sport, but there was much more. He was a factory mechanic, a privateer supporter, the father of a professional racer, and a man who would quite literally help any and everyone he passed along the route of his lifetime. For instance, he was revered by the motocross community in Japan because, through his son Jim’s travels and acquaintances over there, they all knew he was the one man in America they could come to when they needed help, a place to practice, or even a place to stay. Mr. Holley, who passed earlier this year, was a throwback to a time when camaraderie and fellowship were the most important elements in both motorsports and life.

Al Holley.

Andy McClellan was just 27 years old. He hailed from Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania, and was around the local motocross scene for his entire life, first as a promising racer and later as a weekend official who liked to help manage the events and keep an eye on his fellow riders. When he wasn’t at the track he was working with his dad, Craig, another lifelong moto man, in their business McClellan Landscaping. Both Andy and his dad were familiar faces at tracks all over the PAMX and District 5 racing area. Andy was at home one evening in May when he had an accident at home, falling and hitting his head. Paramedics could not save him.

When my dad’s track at Keyser’s Ridge, Maryland, shut down after one year in the fall of 1976, he was approached by two brothers who each had kids that raced motorcycles. Carroll Holbert had three sons racing—Bob, Mike, and Tom—and Jack Holbert had two—David and Steve. The Holberts had a farm in Mt. Morris, Pennsylvania, and invited my dad to see if it might be a good site to build a new motocross track. It was, and all these years later, High Point Raceway remains one of the best-known tracks in American motocross. The Holbert boys all quit racing long ago, but the Holbert family has stayed with the sport in many ways. They have continued to welcome thousands of racing enthusiasts and their families out to the old farm, especially when the Lucas Oil AMA Pro Motocross Championships are in town.

Sadly, the 2013 race—the 37th High Point National—was the first without Carroll Holbert. Carroll passed away in late April, after a full life. He left behind all three of those sons, plus his daughters, many more grandchildren, and countless friends and fellow motocross enthusiasts he met along the way, all of whom drove onto his family farm, which they of course knew as High Point Raceway. The races there will go on, and so will the memory of a good man who loved motocross more—and did more for it—than most will ever know. Carroll Holbert was 78 years old.

Carroll Holbert.

Godspeed to all of the men and women that were a part of our sport who left this world in 2013.