The 1973 season marked the somewhat wobbly introduction of big-time 125cc motocross racing in both the U.S. and Europe.

WORDS: DAVEY COOMBS

PHOTOS: DICK MILLER ARCHIVES

For all intents and purposes, the 125cc motocross story begins in the mid-1960s with Ohio enduro rider/Husqvarna dealer John Penton and his quest to build a lighter, leaner off-road motorcycle. Penton wanted something more competitive than the existing domestic offerings, like the Harley-Davidson 125 Baja, Hodaka’s 125 Wombat, and especially the “department store dirt bikes” from Sears and Montgomery Ward & Co. After being rebuffed by Husqvarna, Penton flew himself to Europe to find a factory that would build out his big idea of a little bike, and he eventually found one in the Austria-based KTM, which to that point produced bicycles and mopeds.

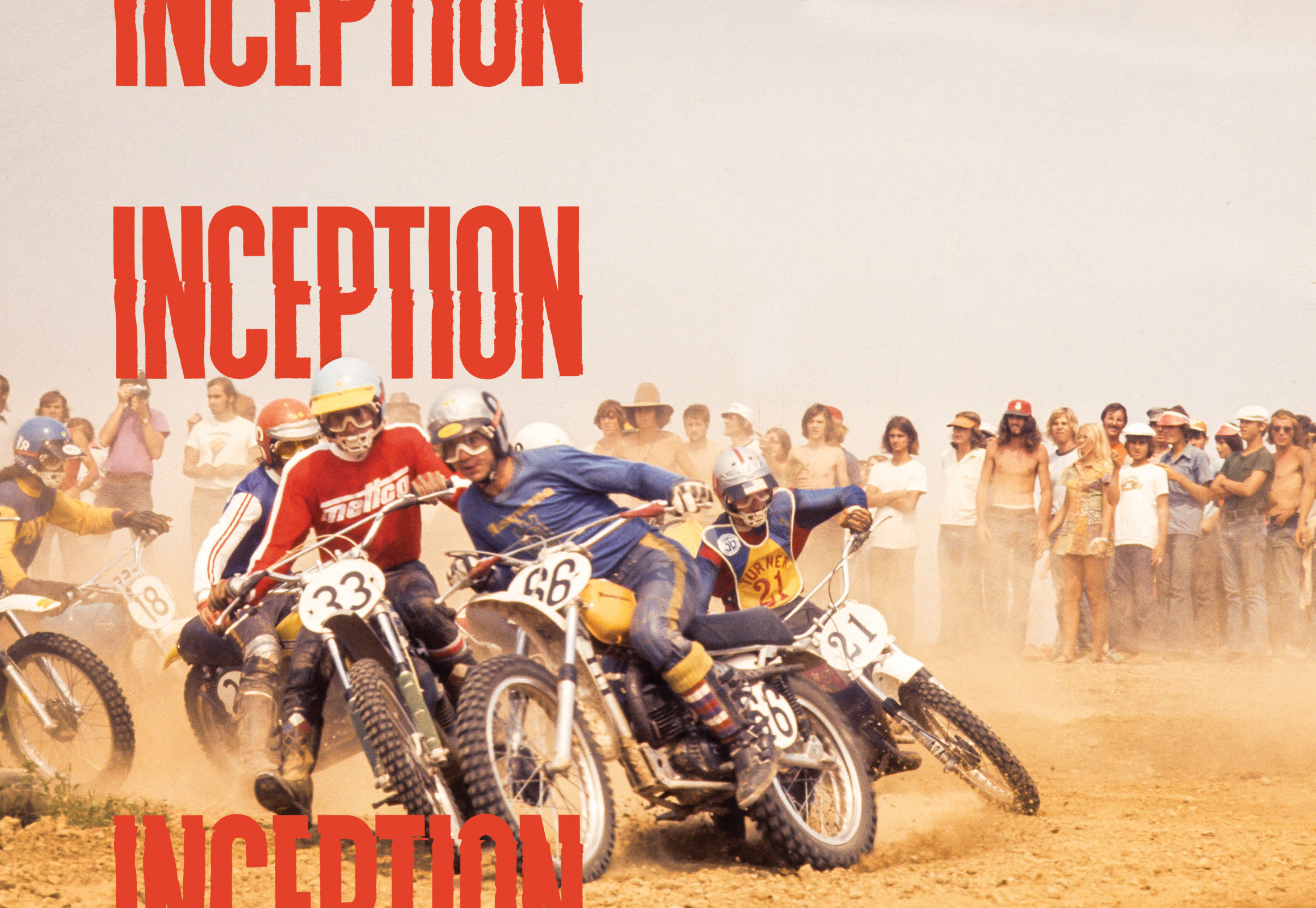

Husqvarna’s Bob Grossi (66) leads

Bruce McDougal (33), and Danny

Turner (21) off the start at the

St. Louis 125cc World Cup race.

ccording to noted collector and moto historian Rick Doughty, John Penton’s initial intent was “to bring a lightweight, purpose-built dirt bike to market for enduro and recreational riding. What occurred as a result was an increased focus on small-bore bikes.” The reception and success of Penton’s 125 in turn led to the development of a stand-alone 125cc class after European brands like Monark, Sachs, DKW, and Zundapp followed his lead. And not far behind them came the Japanese, who were entering the global dirt bike market in almost every category. By 1973 the idea of introducing a new 125cc class was picking up steam both in Europe and the United States, where a full-on dirt bike boom was happening. There was enough interest and participants to start holding big races, but not enough to start a full-blown FIM or AMA championship series for the 125s.

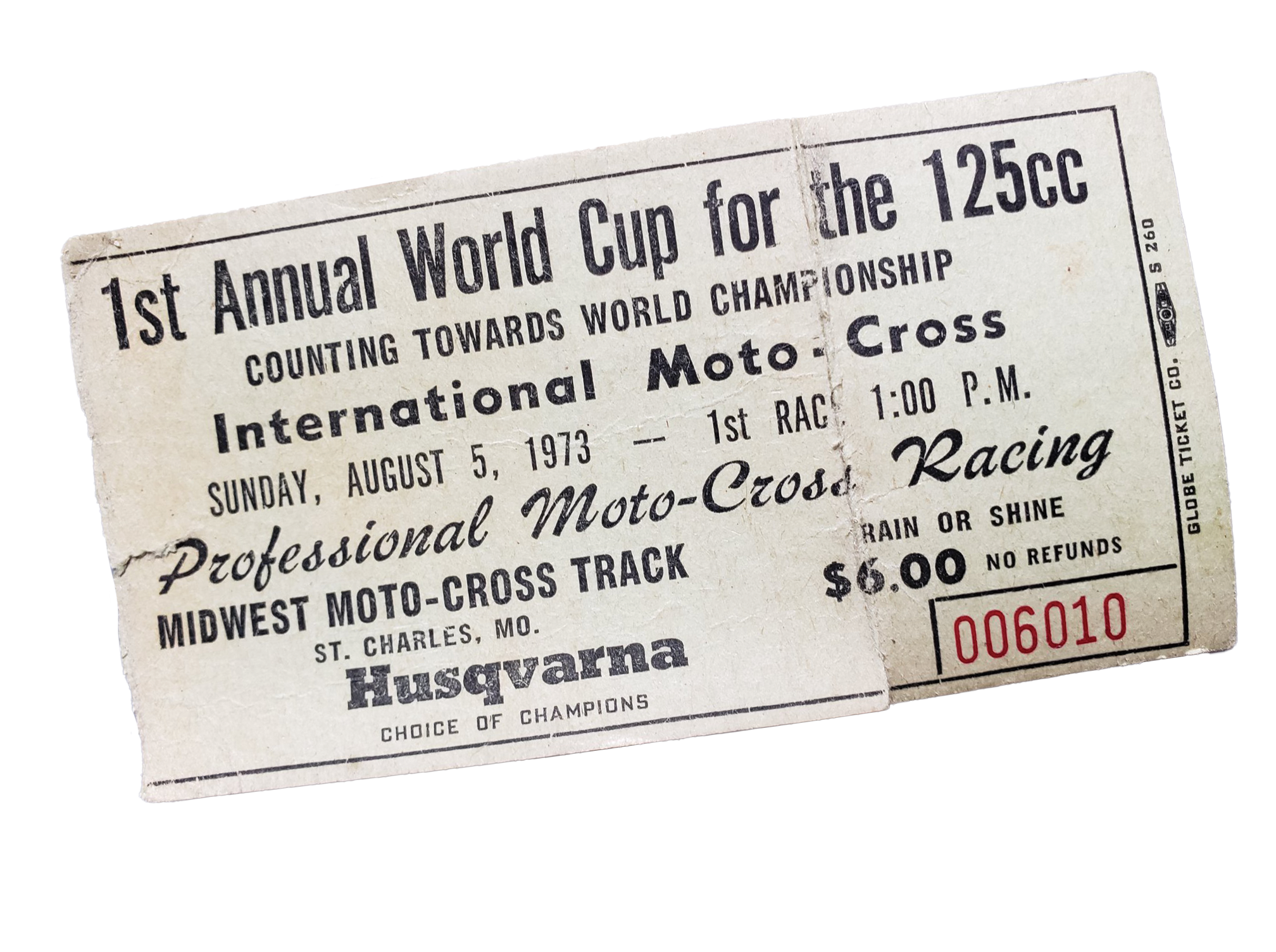

Instead, the FIM would introduce a “World Cup” program with an age limit capped at 25 in order to keep veteran riders from dropping down into what was envisioned as a development class. And like Monster Energy Supercross today, where there are two different 250 regional series, only instead of East and West it would be split into North and South. From each series 15 riders would qualify for a final 30-bike field for a one-race winner-take-all championship. The South rounds were in France, West Germany, Austria, Portugal, Spain, San Marino, Switzerland, and Italy; the North races were held in Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Poland, and the Netherlands. The last round for the North riders would be in the United States, right outside of St. Louis, Missouri, in early September. As for the grand finale, it would be held at the end of September behind the old Iron Curtain at Sabac, Yugoslavia (which is now western Serbia).

Here in the U.S., where the AMA was still not sold on the idea of adding a thd “national” class, a stand-alone, non-sanctioned 125 National Championship would be held at Arroyo Cycle Park (basically Glen Helen’s REM track today). Eighty-eight riders turned up for the March 8, 1973 race. A total purse of $3,200 was up for grabs, with $1,000 going to the winner.

The race brought out a wide range of motorcycle brands. Terry Clark lined up on a Harley-Davidson, albeit one made in Italy. Chuck Bower and Bruce McDougal were aboard Mettco Pentons. Young Marty Smith was there on his Swedish-made Monark. Morris Malone rode a Yamaha YZ125 kitted out by Noguchi. Tommy Croft and Harry Taylor rode Hodakas. Ken Zahrt was there on a Bultaco. And Larry Watkins was there riding a Rickman that still had its headlight mounted!

By the accounts in both Cycle News and the brand-new Motocross Action (which featured the race on its first cover), Billy Payne was fastest aboard his Zundapp-engined Penton, but he kept crashing, as did the young Smith. The overall winner turned out to be Ray Lopez, riding a Penton tuned up by Donny Emler, who later that same year would open his own hop-up shop called FMF Racing.

One month later a 125 class was added to the Hangtown Motocross Classic in Plymouth, though Hangtown was not actually on the AMA Pro Motocross schedule. According to Cycle News’ race report Marty Smith was “top banana” aboard that Monark, with Lopez second overall.

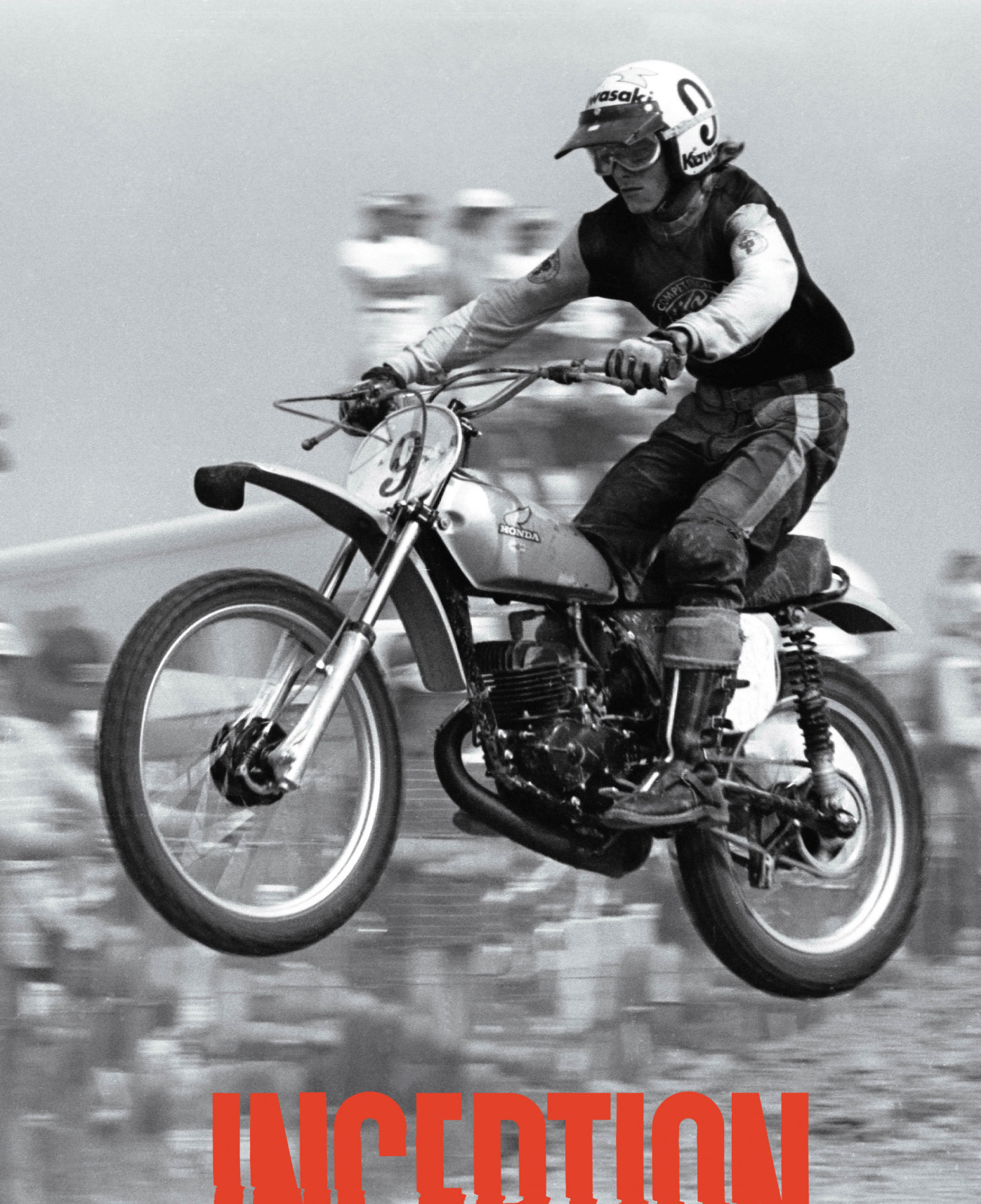

By this point Suzuki was introducing its TM-125 Challenger, Kawasaki was working on one, and Honda was coming out with their CR125M Elsinore, as well as an ambitious contingency plan that offered a $25 gift certificate to anyone who won a sanctioned race aboard one. What no one saw coming was just how sleek and easy to modify the 180-pound Elsinore would be. That bike in particular would prove to be a game-changer.

(Main) Ray Lopez grabs the first moto holeshot ahead of Bob Grossi (66), Bruce McDougal (33) and the rest of the pack. Eventual winner Nils-Arne Nilsson (13) not only raced for the Husqvarna factory, he worked there as well, helping manage support riders like Gilbert DeRoover (14) and more.

Meanwhile over in Europe, the two 125 World Cup divisions were running concurrently. The South was being dominated by Zundapp teammates. Belgium’s Andre Malherbe was a 17-year-old prodigy riding under a French license, as Belgium required riders to be at least 18 to race internationally. The slightly older Schneider hailed from West Germany, and the two of them would each win seven motos in the eight-race series. In the North division one motorcycle was also dominating, but it was the result of one man, not a team. Tarao Suzuki was the Japanese rider selected to campaign the prototype Yamaha monoshock 125. This was the same year that Sweden’s Hakan Andersson would win the FIM 250 World Championship aboard a similar single-shock bike. In the 125 North, Suzuki won every moto he finished, most often followed by a pair of Belgians, Husqvarna’s Gilbert DeRoover, and CZ pilot Andre Massant. Yamaha even made a promotional film about Tarao Suzuki’s efforts that you can find online by searching “1973 FIM Yamaha Motocross Prize Series.”

The final round for the North would be held at Mid-America MX Park in St. Charles, MO, northwest of St. Louis. The promoter would be Edison Dye, the U.S. Husqvarna importer that is considered the godfather of professional motocross in America by importing some of Europe’s best riders to his Inter-Am tour as a way to sell more motorcycles. The St. Louis race was hamstrung from the start due to the World Cup format, where only the nine best motos would count towards qualifying for the final in Yugoslavia. By that point in the season the Yamaha-backed Suzuki had already clinched his spot in the finals, as had DeRoover and Massant. Both Suzuki and Massant decided to pass on the U.S. round to just focus on the final. DeRoover, however, would attend—at the behest of the promoter Dye—and be considered the pre-race favorite. Ironically, Dye had just had a falling out with Husqvarna over his latest dirt bike business venture, the eponymously named Dye Rebel. MXA described the Rebel as “manufactured in San Diego but could easily be mistaken for an English specialty 125 with its nickel-plated frame and Sachs engine.”

When DeRoover and a handful of other Europeans arrived at Mid-America MX Park, they found a track they considered long and easy. It would be dusty too, as the late summer temperatures were near 100, and a common struggle would ensue in simply keeping the bikes running.

Leading the U.S. contingent would be the de facto 125 National Champion Ray Lopez on his Penton, plus the young Marty Smith on his Monark. Husqvarna had dispatched full-time employee Nils-Arne Nilsson, who also happened to be an excellent rider, to participate, along with the versatile Dick Burleson, who was in the middle of an epic eight-title run in AMA National Enduro. The Swedes also handed a 125 to big-bike rider Bob Grossi, who had won Daytona on a Husqvarna CR250 the previous year. They also brought over Torbjorn Winzell who still needed points to qualify for Yugoslavia. Future Motorcycle Hall of Famer Steve Wise drove up from Texas with Steve Stackable to race CZs, while Mickey Boone traveled from North Carolina to race the new Suzuki. Bultaco entered SoCal flyer Ken Zahrt and NorCal hero Danny Turner. Tommy Croft showed up from California on his Hodaka, and Gary Chaplin was aboard a slick rotary-valved Maico. And one of the few Honda CR125M Elsinores that made it into the country by this point was delivered to St. Louis for Arkansas hotshoe Tony Wynn.

The race itself turned out to be a long and dusty affair, as the two 40-minutes plus two-laps motos, as well as three shorter 250cc support motos, wore on both the track and the spectators. MXA reporter Pete Szilagyi wrote of “the unrelenting sun, 90-degree-plus heat, and dust so thick that any rider who didn’t have the course well memorized might easily find himself racing someone for the portacan... Most of the riders thought the dust [was the] worst they’d ever seen, but the promoter made no effort to alleviate the problem even though many spectators left in a huff. It will be a while before they pay $6 to go to a motocross again.” The poor publicity surrounding the event—both before and after—would mark the beginning of the end for Edison Dye in the moto business. Adding insult to injury, not one of the three Dye Rebels finished the race.

The winner/survivor of the ’73 U.S. World Cup race turned out to be the Husky employee Nilsson, who went 1-4 in the two motos. Bob Grossi would win the second moto and finish second overall. Third would go to the impressive Mickey Boone. DeRoover would have an off day, but still finished sixth. As for young Americans like Smith, Wise, Croft, and Lopez, they would all suffer DNFs related to the dusty conditions. (An amazing story is that of Penton Central rider/employee John Harrington, who blew up his bike in practice and then begged Penton to uncrate a bike for him to race. John barely made it to the starting line, then ended up finishing fourth overall!)

Three weeks later a much different and better 125 race took place in Yugoslavia. This was the winner-take-all showdown between Tarao Suzuki on his Yamaha and the Zundapps of Malherbe and Schneider, plus 27 other fast guys, on a remarkable 15 different brands of bikes. (Unfortunately, the two Americans who qualified in St. Louis, Grossi and Boone, did not attend.) The track was an excellent, rough and sometimes steep valley circuit, covered in grass at first and well-maintained. Unlike the no-frills St. Louis race, this one had all of the pageantry that came to be associated with Grand Prix motocross. The finale also had some real drama and skullduggery as well.

In a nutshell, Malherbe won the first moto in Yugoslavia over Schneider after Suzuki had crashed on the start and tweaked his knee. The Japanese rider still managed to work his way up to third, which meant he would have to beat both Zundapps to win the overall, and also have Schneider better Malherbe for a chance to win on the tiebreaker. Schneider led until the closing laps, only to have Suzuki swoop past and into the lead and take off. Realizing that he could not repass the sleek white Yamaha, Schneider instead slowed down and allowed his teammate Malherbe into second to take the overall. Wrote Cycle News’ John Huetter of the late-race shenanigans, “It was one of the most striking displays of effective team riding seen in a long while.”

So ended 1973 and the introduction of 125s to the main stages of motocross. The AMA soon announced that they would sanction a four-race national championship, and Team Honda immediately went on a hiring spree, snatching up Marty Smith, Bruce McDougal, Chuck Bower, and Mickey Boone, who would finish the inaugural AMA 125 National Championship series in that order. The FIM kept the World Cup format for one more year, and it would again be won by Malherbe. By 1975 they were ready to make it a true 125cc World Championship, and for the first decade it would be dominated by Suzuki riders. Malherbe would also eventually end up with Team Honda, with whom he would win three 500cc world crowns.

As for Tarao Suzuki, the knee injury he suffered in Yugoslavia was much worse than he first realized; it would plague him for the rest of his racing career. He would never win another world-caliber event like the ones he did in 1973, and Yamaha would not win the 125 world title until the late eighties. But in America, they would start dominating in 1976 and beyond with a couple of SoCal kids named Bob Hannah and Broc Glover, their bikes equipped with the monoshock system Tarao Suzuki helped develop.

That’s how big-time 125cc racing got started some 50 years ago. In the next issue, we will tell you how the glory days for this class basically ended all at once (and with a bang) in the summer of 2004 at the throttle hand of one James “Bubba” Stewart.

Ready to check out the rest of the March issue? Subscribe to read more! Already have a subscription? Continue scrolling or login to your account.