In the second part of our

history of 125cc pro racing, which

began in 1973, we go straight

to the end of the line:

James Stewart in 2004.

WORDS: DAVEY COOMBS

PHOTOS: SIMON CUDBY

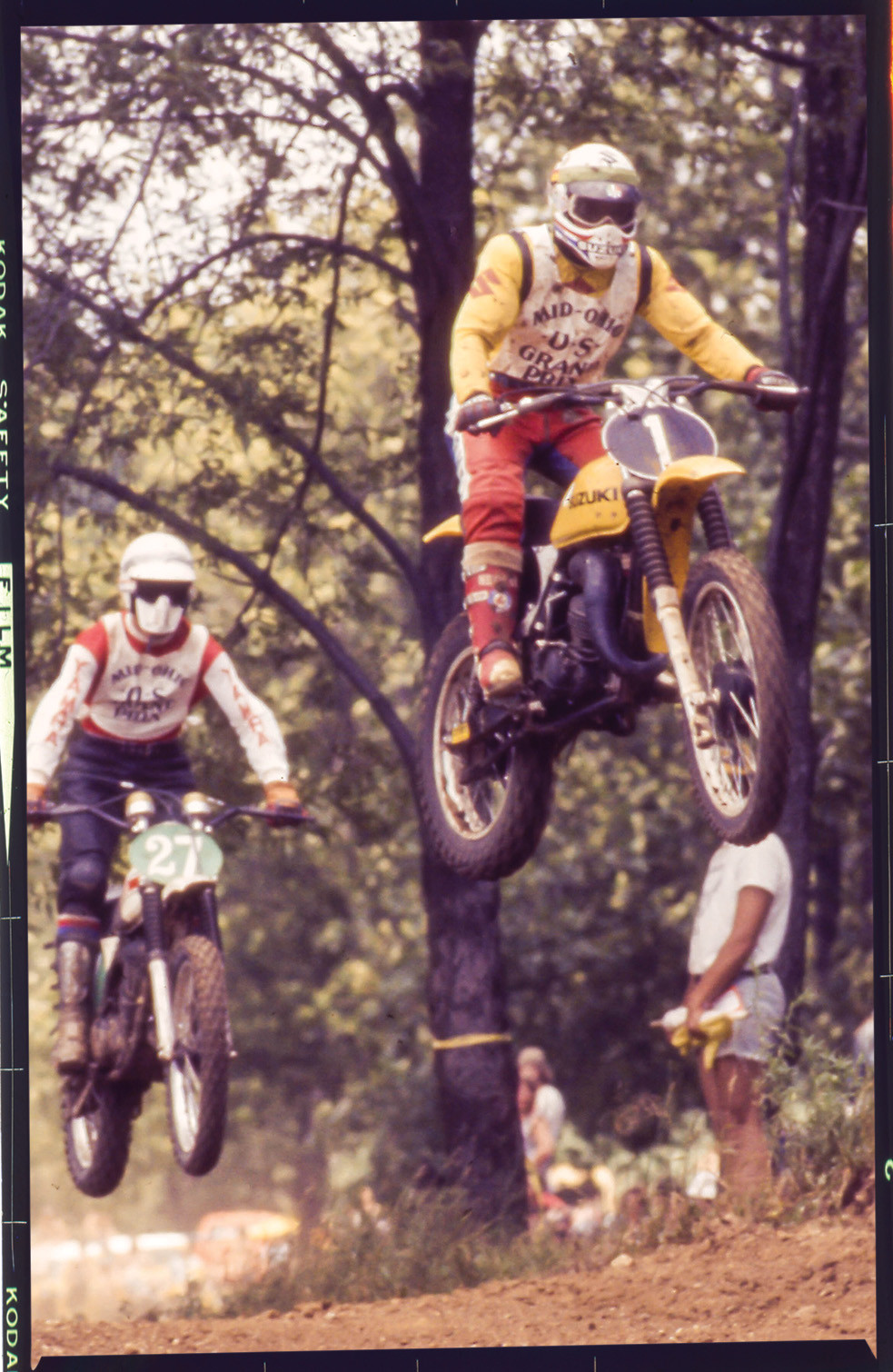

In the last issue of Racer X magazine (March ’24) we told the story of the humble origins of 125cc racing in the feature “Inception” and how neither the FIM nor the AMA seemed to know quite what to make of them. Within just a couple of years they figured it out, and some of the biggest superstars the sport has ever known—Marty Smith, Bob Hannah, Gaston Rahier—were at the forefront of the new class of racing. Inexpensive and fun to ride, 125s quickly became the top-selling dirt bikes in the market and became key in the development of just about every future champion for the next 30 years.

The sudden rise of 125cc racing was only matched by its precipitous fall, which began in 2001 with the introduction of Yamaha’s YZ250F four-stroke to the class, soon to be followed by Honda’s CRF250, KTM’s 250 SX-F, and finally a 250F joint package of sorts from Kawasaki and Suzuki. The writing was on the wall for the 125s before the four-strokes even took their first wins—Ernesto Fonseca in SX (Anaheim 2 ’01) and Larry Ward in MX (RedBud ’01)—because the OEMs were collectively turning their marketing attention (and budgets) towards four-strokes. The absolute end? September 12, 2004. (More on that later.)

There was also the fact that the AMA, FIM, and industry in general got the math wrong back in 1995 when they decided that in order for four-strokes to be competitive against the existing two-stroke 250s and 125s, they would need double the CCs in the case of 250Fs, and nearly double with 450s. At the time the only thumpers being used in motocross competitions were heavier boutique models like KTM, Husqvarna, Husaberg, Vertemati, etc. But Yamaha, who had requested the ratio, would soon change everything with their ground-breaking YZM400 prototype. With Doug Henry at the helm, that bike would win the first supercross it ever entered (Las Vegas ’97) and then its first 250 Pro Motocross Championship one year later.

The 125 class would not really be affected until 2001 because the OEMs focused on their 450 offerings first. When they started producing the 250F thumpers it seemed like the racing landscape would change even quicker, as the bikes were at an even more obvious power advantage over the 125s than the 450Fs were over the 250cc smokers.

Apparently, no one factored in James Stewart.

Bubbalicious

The last 125 National of 2001 at Steel City was won by Ricky Carmichael. Already the 250 Supercross and Pro Motocross Champion, Carmichael asked Kawasaki if he could drop down to the 125 class for the last round of the series for a shot at breaking a tie with Mark “Bomber” Barnett for the all-time 125 National wins record. He succeeded in winning, setting the new standard for the class at 26.

Four months later James Stewart would turn pro. Widely considered to be the fastest prospect to ever come up through the minicycle and amateur ranks, Stewart would hit the ground running as a pro. Riding for the Kawasaki factory team, he won the second 125SX race he ever entered, aged just 16 years, three weeks old. That was the beginning of his assault on the all-time 125SX wins record of 13, held by Jeremy McGrath. And when the 125 Pro Motocross season started later that year, Stewart would immediately win, beginning another assault on another record, the one Carmichael had just set the previous year.

Over the course of the three years that he was in the 125 class James “Bubbalicious” Stewart would not only smash those records, he would do so against more and more competition choosing to race the more powerful 250F four-strokes. While he would crash himself out of his chance to win the ’02 125 West Region in SX, he would win 10 of the 12 outdoor rounds, losing only High Point and Southwick, both the result of mechanical problems. Those wins would go to YZ250F-mounted Chad Reed and Suzuki RM125-mounted Danny Smith, respectively. (There’s a place in the history books for Smith, who rode for the SoBe Suzuki team in 2002: He would end up being the only 125 rider to ever beat James Stewart at a 125 National on an actual 125 motorcycle!)

One year later Stewart would win that 125 West Region easily, but then injure himself at the Las Vegas finale. That knocked him out of the first four rounds of the 125 Pro Motocross Championship and almost certainly cost him the title. Because when he came in, he won every moto for the rest of the season. He also invented the “scrub” along the way but that’s another story altogether. Two thousand and four would be Stewart’s last year in the 125 class, and he would once again dominate in supercross, ending his career in the class with a record 18 main event wins. Outdoors he was even more dominant, winning all but a single moto—he got caught up in a crash right off the start at RedBud and DNF’d the moto, a mishap that cost him what would have been a perfect season.

What was crazy about all of this was the fact that more and more of his competitors were lining up with the rapidly-improving 250Fs. Honda, Suzuki, Pro Circuit Kawasaki, and Yamaha of Troy had all made the transition to 250Fs, with just a few diehards like KTM’s Ryan Hughes and Brett Metcalfe still on 125s. And of course, James Stewart. He was simply untouchable, at least after the first couple of laps when he had to overtake all of the 250Fs that started ahead of him. After that, he would simply disappear.

Bruce Stjernstrom was the Kawasaki team manager at the time. He said the decision to stay on the 125 was Stewart’s alone.

“Before the 2004 season started, we had talked to him about riding the 250 and he said that he was so happy with the 125 he didn’t want to switch,” recalls Stjernstrom. “In fact, we gave him a couple of opportunities to ride it, but he decided to stay with the 125. And we’re like, ‘Okay, but the 125 is a lot of work to make it, you know.’ At that point the 250s we’re getting better and better. But he was just so damn good on that 125.”

By the time the next-to-last round of the series at Steel City came around, Stewart had clinched another title. Before the RedBud crash earlier in the summer Stewart had won 19 straight 125 nationals, another record. Overall he was tied with Carmichael at 26 wins, and the record would surely fall at Steel City—if he could get there. As fate would have it, Hurricane Francis was wreaking havoc on the southeast, making travel from Florida difficult.

“The hardest thing of my weekend was getting out of Florida,” Stewart would later tell Cycle News. I was almost thinking of staying home and trying to break the record at Glen Helen next week.”

Fortunately for Stewart, and unfortunately for everyone else, he made it to Steel City. Riding with a motor finely tuned by Kawasaki’s master engine-builder Rick Asch, James was pretty much out front and alone all day, wheelieing up the steep Pennsylvania hills and waving at the fans off the bigger jumps. He was even the first rider to jump a huge uphill triple in practice, though he thought the wiser of doing it in the actual race. He would easily win both motos, with Suzuki’s young Broc Hepler second on the RM-Z250 and privateer Troy Adams third on a KX250F. The next 125 in the results was 14th place Brett Metcalfe, who Stewart had lapped.

It was afterwards on the Steel City podium, all-time 125 wins record in hand, that Stewart announced he would be racing a four-stroke at Glen Helen.

Endgame

“I had only ridden the 250F one or two times before Glen Helen, and I remembered thinking, ‘This is cheating,’” laughs Stewart. “It was just so easy to ride. My dad thought if I had gotten on it earlier I might have become fat and lazy!

“You know, the way I learned how to ride a bike was to not rev it, but rather to use the gears,” he explains. “So with that four-stroke, with that low RPM, the powerband, the torque—that was all more natural to me. I think a lot of people were just used to me screaming around on that two-stroke, trying to get everything it had out of it.”

I had decided that I was going to try to win by a minute. It turned out to be a minute and twenty seconds instead.

“The 250 we had for him that day was basically stock,” recalls Stjernstrom. “It had a pipe and maybe a piston. The suspension was from our 125 basically, except the shock was different—we had been focused on his 125 and weren’t ready for him to switch like that at the last race.”

Stewart got in a couple of days riding the four-stroke, but with social media not a thing nobody really knew how he would go on it. Maybe he was one of those guys that just can’t ride four-strokes, right? That thinking lasted about ten seconds.

“Before the race I remember laughing to myself, thinking, These guys don’t know what they are about to get into,” he says. “I had decided that I was going to try to win by a minute. It turned out to be a minute and twenty seconds instead.”

Stewart led every lap that afternoon, with a combined winning margin of nearly two minutes between the two motos. His fastest lap in the second moto was almost five seconds faster than that of the next fastest rider (Hepler again) and he set 11 of the 13 fastest lap times of the entire field. Only Ricky Carmichael was faster in what would turn out to be his last race ever on a Honda CRF450 and the final piece in another 24-0 perfect summer.

I happened to be the ESPN2 pit reporter that day. When I interviewed Stewart’s mechanic Jeremy Albrecht during the first moto he said, “I think it’s probably good we didn’t ride [the four-stroke] all year. I think it made it a little bit more fair.”

And then towards the end of the last moto I asked Albrecht about the new bike, he shrugged and answered, “Yeah, it’s cool to see him out front, having fun with the new bikes—four-strokes are always cool to ride—looks like he likes it.”

A Place in History

We Went Fast’s Brett Smith was also working for ESPN that race, filling in for color analyst Cameron Steele. I recently asked him about James’ last season on the 125 and just where it belonged as a historical milestone in motocross.

“Maybe the lens from which I view Stewart’s ’04 Pro Motocross season is rose-colored but his 23-1 performance that summer is understated, underrated, under-appreciated and underreported,” offered Smith. “And it’s a record that cannot, and will not, ever be repeated. He was one of the very few riders to compete on a bike that actually matched the displacement name of the division. Stewart was severely underpowered that summer, and his dominance is a testament to how good Stewart rode a motorcycle.”

It was also the end of an era. With Stewart on a thumper in that last race, the highest finishing 125 was 13th place for KTM’s Metcalfe. Second-best? That went to 31st place Cole Siebler on a Suzuki RM125. All told, there were just four 125s in the 40-rider final field.

“I struggle to recall if we knew that Stewart’s decision to ride a four-stroke at that last race was, effectively, the death of the 125 two-stroke as a competitive option in professional racing… But we had to know, right? Maybe our subconscious had already buried the inevitable. Because if it were not for Stewart the 125 would have died long before. So we had 30 years to prepare for the end of this era that began with Marty Smith and ended with James Stewart.”

Smith is right. While 125s are still out there on some showroom floors, and 125cc racing in amateur motocross is still big in Schoolboy classes, their days of competitiveness ended on Sunday, September 12, 2004, the very moment James Stewart parked that KX125.