The People Involved

Owner, No Fear

Owner, No Fear

Owner, No Fear

Owner, No Fear Motocross/No Fear marketing manager

Owner, Life’s a Beach

Owner, Life’s a Beach and No Fear; Currently a helicopter pilot

Owner, No Fear Motocross

No Fear athlete

No Fear athlete

Life’s a Beach/No Fear athlete

No Fear designer

No Fear Golf

No Fear marketing

IndyCar racer

No Fear distributor

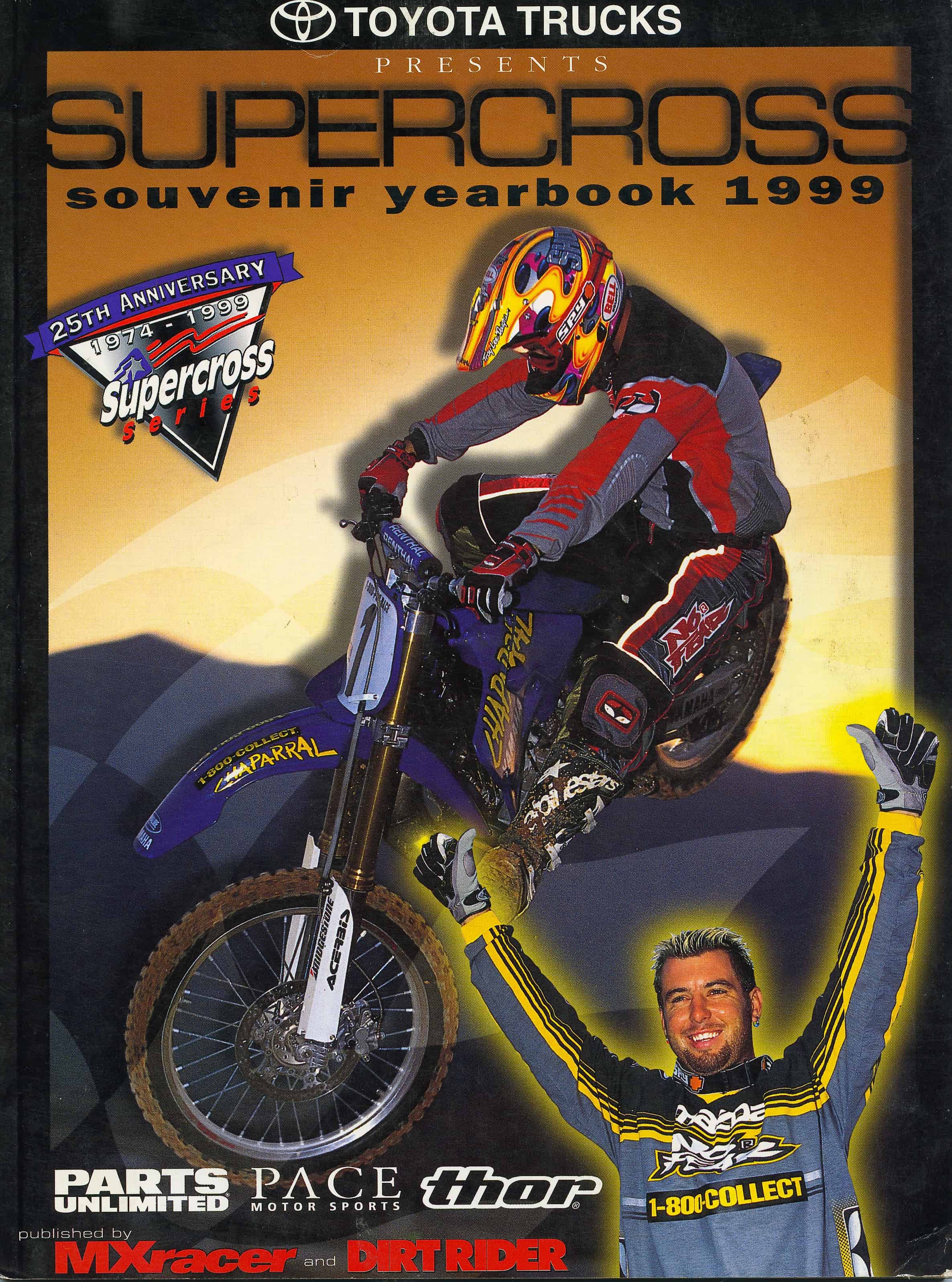

What comes to mind when you think of No Fear? Maybe it’s the motocross gear that took the world by storm when Jeremy McGrath wore it in 1999? Or maybe it’s the T-shirts whose slogans suggested you were pushing the edge? The sticker on your truck? Travis Pastrana?

Whatever it is, if you’re reading this and of a certain age, you had something from the company started by Mark and Brian Simo in Carlsbad, California. (I personally still have a No Fear keychain from 1992 on my keyring.) Although estimates are hard to nail down, at one point the company had close to $200 million in annual sales, and that was just in casual apparel—never mind the motocross-gear branch owned by Jeff Surwall and McGrath.

It’s an amazing story with threads running through several of our sport’s finest eras—a great company, started by a couple of motocross racers, that conquered the world of action sports, if only briefly.

The story of No Fear begins with the story of Life’s a Beach and the early 1980s Illinois motocross scene.

I got into motocross probably in my early teens. It wasn’t until we started racing that I met a cast of characters from Illinois: Jeff Theodosakis, or Beaver, as we call him, Laurens Offner, [and] Jeff Surwall. These are people we met at the track probably when we were 15, 16 years old. We were all going to the same tracks, but we didn’t even know each other.

All four of us were always working hard to afford to go racing and get by. None of us were spoiled or had everything handed to us, so you kind of had to work hard to get it. So you get creative.Jeff Surwall

First I met my future brother-in-law, Beaver. Then I met Mark and Brian [Simo]. I was, like, 14, then just got to know them a lot better when I turned 16. I had a pickup truck and I could drive, so we’d go riding together. They’re a year older than me, and Beaver’s a couple years older than me. They’d come out and ride where I had tracks, and I’d go out where they rode, and then we’d see each other at the races on the weekend. Got to know each other a lot better because all of their parents wouldn’t go to the races and my parents were always there with a motor home. My mom would feed everybody, so they’d pit around our camper.

Brian Simo and I met on the racetrack. Ended up in a little shoving match, then we became good friends. Started parking next to each other, then going to races together, then sharing everything.

There was a whole group of guys down there. Beaver was really good, Jeff was good. They all kind of competed together. Jeff Surwall and I would go to Florida together all the time. He was a regular going down there. Beaver joined us later and started going down to Florida too. We all kind of would migrate. We had a little crew of us that would head down there and ride in the Winter Series.

Mark and Brian were both good. At the time it was B class, but good intermediate. Beaver was a good A rider in our region. Never raced pro or anything, but they did amateur supercross at Daytona.

Mark and Brian, in prior years, had gone down to the Florida Winter Series. In ’84 they said, “Beav, come down with us this year.” I’d already kind of hung up my bikes. I went to college, got a culinary degree and a degree in restaurant management down in Florida. I was back in Illinois running restaurants, and they said, “Come down with us.” So I said, “Okay.” I got my stuff covered and I got a new Yamaha. Then we loaded up in the big trailer. Got down there in January and started training and racing. The boys brought chainsaws down there and we were cutting trees and doing what we could to make a buck during the week and then racing on the weekends, training, having a ball.

We’d have 20 different styles, and we’d hang them with a clothesline and clothespin and we’d say 20 bucks. It was all one size. If you weren’t our size, that was your problem.Jeff “Beaver” Theodosakis

All four of us were always working hard to afford to go racing and get by. None of us were spoiled or had everything handed to us, so you kind of had to work hard to get it. So you get creative. So I think everybody had a good work ethic and kind of knew how to get what you want by working for it. I think it helped set them up for the rest of life.

I started dating a gal named Debbie who had an apparel company called Meet Me in Miami. It was a women’s line. She had sewing machines, cutting tables, and was training people. We’re down there, and shorts were short. Guys are wearing, like, 1” inseam shorts. We’re like, “Man, we’re not wearing those things.” So we went to Debbie and said, “Debbie, make us three pairs of shorts. We want them to go down to our knees.” She goes, “All right, go get me some fabric.” So we pulled some curtains off the wall somewhere, or some tablecloths. Crazy stuff. She goes, “Well, this isn’t really shorts fabric, but we’ll make them.” So she made us a little one-piece pattern that you flip, taught us how to cut, and stood there where they sewed them and started teaching us how to sew. We made three pairs. We started wearing them around at the races and on the beach. We were staying in Fort Lauderdale. That was our base, and then we would travel to the races.

We had a lot of people ask us about the shorts, and then it’s kind of like, “Maybe we could make some of these and make a little money.” Back in those days, you burned up all your money living there at the end of the racing series. You didn’t want to go home because it was too cold, so if you could find a little extra money, you were motivated.

If I’m not mistaken, we went to Florida with motorcycles and came back with sewing machines.Brian Simo

Then Spring Break 1984 hit there, and there were millions of kids everywhere. So we started wearing them around, and most people thought we were idiots. They’re like, “What are you guys doing?” We didn’t care. We had power in the three of us. If one was down, the other two would lift him. If two were down, the other one would lift him. We were kind of invincible when the three of us were together. So we’re wearing these shorts, and after about a week or so, seven of our friends said, “Get me a pair of those.” So we made seven more. Then we were like, “Hey, maybe we should try to sell these.” We made 30, we peddled those. Then we said, “Okay, this is cool.” I think the next batch was 100.

It wasn’t really a business plan. It was more like, hey, let’s talk this girl into making us some shorts, and she did. She made the first 50 pairs. We walked up and down the beach and sold them for $20 apiece and go, “This beats the heck out of working.” One size, real simple. Then we kind of said, “Hey, let’s make a lot more of these since everybody wants them.” That’s when we decided to make 1,000 pairs of them.

We would just go buy random fabric down in Miami, because we kind of couldn’t find stuff. So we had these little rolls of this, little rolls of that. We just threw it all together. We’d have 20 different styles, and we’d hang them with a clothesline and clothespin and we’d say 20 bucks. It was all one size. If you weren’t our size, that was your problem.

She couldn’t make us 1,000 pairs, so she introduced us to a little factory down in Miami. We’d comb the little fabric shops down there, buy some fabric, have them sewn, and then walk up and down the beach and sell them. Until one day the police stopped us. They said, “You guys can’t be doing this, you’ve got to go across the street and sell them at the stores.” All of a sudden, a business is formed. We decided to start selling them in stores.

[Debbie] turned us on to this gypsy-type guy named Victor down in Miami. He was a real shady, greasy guy. We had to watch him all the time on our accounts and stuff. He had a big factory. Twenty-six sewing machines, cutting machines. So he’s making our stuff, and he calls us. He goes, “Guys, do you want to buy this factory?” We’re like, “No, we want you to just make our stuff.” He goes, “Well, I’m getting closed down for tax evasion, and if you want to meet me in the middle of the night, I’ll sell you all this stuff.” We’re like, “How much do you want?” It was like $4,000. At this point, we each have a practice bike and a race bike and our trailer, a big Holsclaw, filled it with everything. So Mark, without even asking, takes our six bikes to Fort Lauderdale Yamaha. He gets six grand for our six bikes in cash. He goes, “Let’s go buy that factory.” I guess we don’t have bikes anymore! But the series was done. We had all finished racing. So we take that money, and we meet Victor at like three in the morning. We take the same trailer that had our race stuff in it and loaded it up with 26 sewing machines, cutting tables, cutters—the whole full factory. We set it up in our apartment in Florida. We put an ad in the paper. We had ladies come in and sew for us.

If I’m not mistaken, we went to Florida with motorcycles and came back with sewing machines.

The name itself, we ran into a guy at a store down there, a little seashell shop, a guy named Isaac. He said, “I heard about you guys. Everybody’s been talking about these shorts. I’ll buy everything you’ve got.” He looks at the shorts and he said, “I love the shorts, but you need to have a name on here.” So on our way back with an arm full of shorts he said, “We’ve got to come up with a name.”

Debbie had a book about the Australian beach lifestyle called Life’s a Beach. I remember seeing that book, and I was like, that would be a great name. So we got the trademark and went with that.

So Life’s a Beach just seemed appropriate. We were living at the beach, and it sounded like fun. There was no plan or rhyme or reason to it. It was just fun. It sort of spoke to the time.

I don’t know how many kids came down [for Spring Break], but some crazy figure, like seven figures, came down to South Florida. That was the place to be. You couldn’t drive because the Strip was just stopped with cars. So we had these beach cruisers and duffle bags we’d fill with shorts when we were getting them made. Driving down the beach and peddling them to the shops, peddling them to the kids. Twenty bucks, one size fits all. Just coming back with all this cash and then doing it all again. Then we started bringing them to the races. Gainesville National was getting towards the end of the season there in 1984. We got to the race, got our clothesline up on our trailer across from a palm tree selling our shorts.

I said, “I want to wear these shorts over my pants. Are you cool with that?” He said, “If you win the first moto, you can do whatever the hell you want.” So I did.Rick Johnson

The very first time I met those guys was in the parking lot of the Howard Johnson’s at the Gainesville National in 1984. Broc [Glover] and I were walking around. That was back when they had the tech inspection and stuff the day before at the hotel, and then they had the race the next day. There were these three dudes, Mark and Brian Simo, and Jeff Theodosakis who were hanging. They were kind of stray-cat-looking dudes. All in good shape, fit, wearing these big-ass baggy shorts. They had a Toyota Land Cruiser and a three-foot-tall sided U-Haul trailer packed with these shorts with everything from tiger stripes, all this different shit.

We raced the amateur the day before the Gainesville National, the Saturday. Then the pros were coming in. So we’re standing there selling our stuff and Ricky Johnson and Broc Glover walk up. We’re, like, elbowing each other like, “Holy shit! It’s Ricky and Broc!”

We taped shorts on the side of a trailer and thought, “If they sell at the beach, maybe we’ll sell a few at the races.” Ricky walked up. He saw they were taped on. He goes, “Can I have a pair of those shorts?” We’re like, “Yeah, 20 bucks.” He’s like, “No, you don’t understand. Just give me a pair.” It’s like, “No, they’re 20 bucks.” That was kind of the beginning of our relationship. It was kind of funny. I think Ricky kind of appreciated the fact that we just didn’t really give a shit who he was.

There wasn’t a person at the race that wasn’t looking at that going, ”What is going on here?“ Suddenly we learned what marketing was.Mark Simo

I went over to them and I said, “Hey, is it possible to get some shorts?” So they said yeah. They gave me a couple pairs, and they gave a couple pairs for Broc too. It was kind of cool. They were good guys. I said, “I’ll ask my team manager if I can wear them over my pants.” This was back in the day when dolphin shorts and the Nike running shorts was the trend. There was nothing big and baggy around at that time.

Rick was always one to kind of do something to where it would possibly draw some attention. He always had fun, and he had fun pushing the envelope.

So I said to [Yamaha team manger] Kenny Clark the next day at Gainesville, I said, “I want to wear these shorts over my pants. Are you cool with that?” He said, “If you win the first moto, you can do whatever the hell you want.” So I did. I won the first moto in 1984, so then the second moto I grabbed some teal green, kind of aqua-blue tiger-striped shorts, and I put them on over the top of my Sinisalo pants. So I got the holeshot and was leading, then my shock blew up so I ended up getting I think fifth or sixth or something, or tenth. I can’t remember. But during the race, the guys ran to the fence. They look, and here’s me winning the national with these shorts on!

So we’re selling our stuff again, and we hear on the loudspeaker, “Start of the second 250 moto….” We’re like, “Oh shit, we’ve got to see if Ricky’s wearing our stuff.” We take our clothesline down, pile our stuff in the trailer. We’re parked way the hell out there and we’re sprinting. We don’t want to miss the start. We’re like, “Shit, we missed the start.” There’s this giant cloud of dust. Then the dust clears and in the front is Ricky wearing our blue tiger-striped shorts over his yellow leathers and jersey!

RJ threw them over his pants, as we all know from the history. That was kind of a beginning of it. The Life’s a Beach brand was just getting underway at that point too. So in the moto world it certainly drew some attention to it.

It was hilarious. Who would go race and win a national with a pair of surf trunks over their gear? It was just unthinkable, and it was entertaining as hell. There wasn’t a person at the race that wasn’t looking at that going, “What is going on here?” Suddenly we learned what marketing was.

Everybody’s like, “What the heck is that? Johnson won with tiger-striped shorts on? A lot of little things fell into place, and it kind of took off from there.

Everybody came over. “Do you have those shorts that Ricky was wearing?” The problem was it was a blue and black tiger-striped shorts. We didn’t have a lot of them. Sold those out instantly because everybody had to have the shorts Ricky was wearing. It was a pretty good lesson.

So after the moto, the guys ran back to their trailer and they sold them all out. So immediately we started to keep in touch.

The Move West

So then we came back to Illinois after the season all died down in Florida. In May it was all quiet. We brought our stuff back to Chicago just to regroup. I headed out to Carlsbad, and the only reason I knew Carlsbad was an awesome place to be is because I went to Suzuki School of Motocross in 1976 with Mark Blackwell and all those guys. I’m like, “Guys, I know a really cool spot.” Actually flew into Long Beach, and I bought a ’60 Chevy convertible I was looking at because I restored a bunch of old cars. I drove it down to Carlsbad and slept in the back of it for a week or so and then found a little place to rent. I said, “Boys, I got the place.” Then they came out. It was, like, September. So basically we were in Chicago from May to September.

We came to Carlsbad and said, okay, let’s get started. We really didn’t know anything about doing anything like that. We got a little marketing lesson from Ricky, and we got friendly with him out here. In fact, in those days, El Cajon was really the hub of all things motocross. As a Midwestern guy you go, “I’ve got to go to El Cajon.” Marty Smith, Marty Tripes, Tommy Croft, Ricky Johnson, Broc Glover—they were all there. So we just came out here and we were in heaven.

Being from San Diego, born and raised, and that California lifestyle kind of a thing, you could always tell when there were guys that were not from Southern California and that area, but they wanted to be. When the Life’s a Beach thing came out, that was that whole group of them, no question about it. They were all Californians that just happened to be born and raised in the Chicago area. We all got along great and had a lot of fun. You’ll have a ton of laughs with any of those guys.

I had gone with Marty Moates for two years on the national circuit and the Trans-Am circuit and did all that when he rode for LOP Yamaha that was owned by a guy named Laurens Offner. So I spent some years out there. In those days, you’d drive a box truck around. With Jeff, I would haul his bikes in Marty’s truck, and nobody knew about it. Laurens would have flipped if he found out that I was taking Jeff Surwall around in Marty’s truck. So I knew some of the folks.

When we drew the Bad Boy, the idea was to have this just badass little tough guy that doesn’t give a shit, just kind of punk. When we drew it on the kitchen table, we’re like, “That’s it.” Boogaloo and I got in my ’60 Chevy and drove up to Laguna Tattoo and we each got tats on our arms.Jeff “Beaver” Theodosakis

I was talking to a friend and he goes, “Yeah, the Simo brothers live out here with Beaver. They moved Life’s a Beach out here.” So I called them and we started hanging out and we struck up a friendship. That’s when I started wearing Life’s a Beach.

We grew really quickly, and there was kind of a concept that was floating around: how are we going to fund our growth? Laurens was very interested. He had actually come out here to California too. He was financially capable and interested in sort of running the business through a license deal. So we did a license with him for three years. I wasn’t really happy with the way we were going. It wasn’t really the right direction for me and for what I thought we should be doing. Now we had two brands. He became a licensee. He didn’t own the brand at that point.

I raced for Team Honda in the early to mid-eighties on three-wheelers and knew RJ well. Ricky took me out one night to a club, and I want to believe that’s where I first met [the Simo brothers and Beaver], in that kind of environment. Then Ricky goes, “He’s riding for Team Honda. He’ll get you a lot of coverage.” Back in the day, it was kind of funny, but every sticker that I had on my bike basically paid me some kind of money. I know those guys didn’t have anything, and they were really cool when I met them. I just kind of wanted to, because of Ricky, help them out.

Down in Florida, we met a guy named Mark Baagoe. We call him Boogaloo. He was an artist. He was the guy who took us surfing for the first time. He followed us out to California shortly after we got here. None of us were designers—that wasn’t really our skill. We were kind of more into creating a market for ourselves, but this artist came out here, and he was the one that kind of wrote the script for Life’s a Beach and drew pictures of sharks and little characters. His art was uniquely commercial. So during that period, he actually sketched out the little Bad Boy character in our kitchen. We saw that and we thought, “That’s a really cool idea.”

At the beginning of ’86, they started the Bad Boy Club, which was through an artist named Boogie, Mark Baagoe. I don’t know exactly the origins from it, but he drew one of the original Bad Boys. We all had flat-top mullets at the time, and we cut each other’s hair and all that stuff. So that’s how it all took off.

I got the Bad Boy tattoo on my right arm the night we drew it. It’s not going anywhere in my life. I look at it every day. Boogaloo, our artist, when we drew the Bad Boy, the idea was to have this just badass little tough guy that doesn’t give a shit, just kind of punk. When we drew it on the kitchen table, we’re like, “That’s it.” Boogaloo and I got in my ’60 Chevy and drove up to Laguna Tattoo and we each got tats on our arms.

Right around that time, skateboarding started to get really big. We kind of thought this is a great entry for us to kind of be there, because the Life’s a Beach thing didn’t make a lot of sense there. So we decided to go after that. I took a little more interest in learning about trademarks and how that works. So we got the Bad Boy Club mark and Life’s a Beach mark. As things go, we were really well-timed with where the market was. The market was underserved. There were a lot of people interested in what we were doing. We were having a ton of fun. There was kind of a movement out here, obviously in the coastal areas, the surf and snow thing, snowboarding and wakeboarding and surfing. The board-sports stuff was really starting to just get going. We kind of came from the outside, so we sort of brought the other element of the extreme sports into the community.

[Scott Cox] was good friends with Ricky. He’d be like, “Let’s go get you a buzz cut.” We’d put that in the magazine. Just all the goofy antics that Ricky would do. We would live off that energy.Jeff “Beaver” Theodosakis

Mark can back this up, but I literally sold the first thing that came off. Then the next thing, I’m going to all the races in a 10’ x 10’ tent with not even $300 in my wallet, just trying to sell $300 worth of product and turn in the $600 and keep me from getting a real job, to make $300 a week. It kept getting better and better.

During the Life’s a Beach days, I was busy racing. If I could help by “This guy’s a friend of mine, he owns a dealer,” I would do that kind of stuff. But it was mostly just helping my friends do what they could. I was busy worrying about trying to be a racer.

RJ At the Coliseum

At the end of 1985, the Rodil Cup at the L.A. Coliseum pitted some of the best racers from the USA against top Europeans. Since the Euros had less supercross experience, the promoters put the faster Americans on the back row to start the main event. Not all the American riders were on board with that.

I had already signed with Honda. I was testing with Honda, but that was at the end of ’85, so I was still legally under contract with Yamaha. Yamaha wouldn’t release me, so I couldn’t ride a Honda, and they wouldn’t give me a bike. So I talked to Jim Castillo from CTi, and he had this cool bike. Then Jake from Showa somehow had a pair of works Showa forks. Then Mitch Payton did the motor. So we said, “F--k it, I’m going to come out there with a goddamn suit on and with this and that.” Fox [RJ’s gear sponsor] didn’t care. We were going to have fun. I’m wearing a Yamaha helmet with stickers on it and covering this and covering that. We were boisterous. Then I, like an idiot, in the first moto, I’m like, “This will be cool, man. All of us fast guys will start on the back row and we’ll see what it’s like.” So I go out in the first heat and I win, and then everybody else decides to play the smart role [sandbagging to start on the front row for the main]. Not one of my proudest moments. I don’t know where the hell I got that rag that I’m wagging around in the air.

Ricky won L.A. Coliseum SX [ed. note: He didn’t win, but he did “win” the night with his speech] with our shorts on over his pants. So we ran these ads, and we started, like, a direct-to-consumer business. Back then we were usually just selling to dealers. But we started Too Hip. That was the nickname Ricky had.

Wearing those shorts at the Rodil Cup was a big help to move product. They were selling through surf shops and stuff like that. We were trying to get them into motorcycle shops. Kids were calling from all over the place wanting the stuff. So we said let’s come up with a company, and we called it Too Hip. Stevie Wright was friends with Scott Cox, who had an advertising agency, so we put together some ads and stuff. We did Too Hip, and it was mail and call-in, because there wasn’t internet or anything like that. So there would be an ad in Motocross Action or Dirt Rider or Super/Motocross magazine. People would call in and we’d ship the stuff.

So we’d do all the goofy ads with Ricky getting his hair cut, and just fun stuff like that showing our gear. It was all direct to consumer. Scott Cox was kind of the creative director behind that and did all the great shots. Great guy. He did so much for us back then. He was good friends with Ricky. He’d be like, “Let’s go get you a buzz cut.” We’d put that in the magazine. Just all the goofy antics that Ricky would do. We would live off that energy.

These shorts, they were not a generic-looking pair of shorts, usually. If you had them on, people either saw them or wondered what they were. They stood out. So if someone wanted them, it was easy to tell what they were. I’d give them phone numbers or whatever I could do that way.

Ricky’s a curious guy. He likes to try things. He loved the idea of the whole lifestyle. He loved to have fun. So basically it was just all of us really getting together and having a good time. He really adopted the Bad Boy [character]. That became sort of the image that we all had, the whole group of us, and the Bad Boy Club became this group of guys.

We just started thinking of other cool stuff. We had our sharks and our skulls and our bats and switchblades and chains. We said, let’s do some more interesting stuff. We just always loved The Jetsons. We got a hold of Hanna-Barbera. We wrote a license with them, and then we got to use Elroy and George. We did the print. It was a 13-color print, the Jetsons print. Then we said, Three Stooges were our heroes. I still have the painting that was in our old offices. I have it here at my home now. We lived our lives like we just took notes from those guys on how to live. So we got a hold of Moe’s daughter somehow, and we wrote a license with the Three Stooges too. So we had Curly on shorts. We had Three Stooges film-reel stuff.

It was pretty simple back in those days, and that was, I think, the more enjoyable part of it. At that point, it wasn’t complicated. We really only made shorts, and then later T-shirts. T-shirts weren’t even the big part of the business in the early years. It was mostly the shorts. We had like the Jetson characters and the Bad Boy. All that stuff was pretty simple. Stickers were probably the most ridiculous thing. Oakley probably was one of the ones that started it, but putting stickers—we had them on every car in the country. It was great.

I was blown away with Life’s a Beach. I was just a kid, kind of looking in magazines at that time. I didn’t race yet. I think when [RJ] started wearing Life’s a Beach, of course we all loved RJ. He was my hero. He was everybody’s hero. So for me, people were kind of like, “What was that? Why would he rep those shorts over his pants?” I guess back in the day the gear contracts weren’t that sticky where you could do something like that. I think everyone was probably pretty shocked about it.

The brand was still really hot, but under-distributed. So I opened up the first Life’s a Beach store in El Cajon. We had a big grand opening and [San Diego radio station] 91X there. Just thousands of people. We had skateboard ramps in the parking lot back in the early eighties. It was the strip center right off 2nd St. It was called the Harvest Ranch. It was kind of cool. The story gets even better. I think Ricky’s wife today, Stephanie, worked for me when she was like 16 or 17. We always laugh. She used to wear these neon skirts. I’m sure that stuff’s getting ready to come back in. We both had really busy schedules, working probably 45 weekends out of the 52 weeks in the year.

The sad thing about it is money shouldn’t come between friends. Sometimes it does.Mark Simo

It went from about ’84 to ’89, and it was just sort of straight-up growth. That’s when we had problems capitalizing the growth.

In 1987 we had brand-new 250 Hondas, all three of us. We had Mitch [Payton] from Pro Circuit dial them all in for us, pipes and suspension. They were all bitchin’. Just broken in, maybe ten hours on them. We had five or six employees at Life’s a Beach then. Coming in one Monday, we were like, “Guys, how are we going to make payroll? We’ve got to pay our employees.” We can’t do it. So we told Marty Moates. He was a friend and a teammate since the seventies. Jeff Surwall and Marty were on the LOP team. Greg Thiess was on there, too, but it was me, Jeff Surwall, and Marty early on. So we said, “How are we going to make payroll?” We’re looking around. What can we sell? We’re thinking about any ways to bring up cash. We all kind of glanced over at our three bitchin’, perfect bikes leaning against each other in the warehouse, and we’re like, “We’ve got to sell them.” So we said to Marty, “Can you find someone that’ll buy these things?” So he found a guy, and we sold them for like 60 cents on the dollar, but we needed the money to make payroll. I remember tears in my eyes as I rolled that bike up the ramp onto the pickup truck. We got three of them in there. I was thinking “This is the last motocross bike I’m going to own.” And it was.

We gave up a lot of stuff for money. We were all-in. That really happened.

Back in those days, we would find someone in Japan that wanted to distribute the product, and it was sort of like they became our bank, because they would pre-pay the product and help us fund our business because they wanted American brands. So we found whatever clever trick we could to keep it going, but in the end, the growth outpaced us. That’s when the licensing scenario came up where Laurens had the resources to take it to the next level financially, but it was not necessarily, in my opinion, the right thing for the whole brand and direction of the company. That’s how we got that problem. That’s was the beginning of the end of my and Brian’s involvement.

We were doing, I think, $6.5 million in 1989. Then we had Bubble Gum Surf Wax in the building with us, and they were doing about eight or nine hundred. Then another brand called Mambo, which my brother ran. So I think our collective was about $8 million in our building.

The sad thing about it is money shouldn't come between friends. Sometimes it does. There’s a lot of perceptions of how well certain people did or didn’t do. In the Life’s a Beach days, when Ricky said he wasn’t getting paid a lot of money, we weren’t either. We were so undercapitalized, we ended up having to license the brand up just to stay alive. So there wasn’t money to spread around in those early years. We weren’t making money like that. The perception of it was much bigger than the reality of it.

I never saw any money from it. I think they made some money from it, and I didn’t. But I didn’t pursue it real hard. So I got some free shorts and I got free clothes. We did some ads. We had a lot of fun, and they bought me dinner most of the time.

Bad Boy Club and Life’s a Beach was just a bunch of guys getting together and making stuff happen, but for the better part of that time, three of us lived in a house, sharing a house and sharing cars. I think that people perceived a lot of our success as always being successful. It was brought up to me not too long ago. Someone said, “Gee whiz, everything you guys have ever done has been successful.” I said, “Well, that’s not true.” We stuck in every fight long enough to end up on the top side of it, but most of what we did was an adventure, not necessarily a success. I think there was a lot of people and businesses that grow quickly or businesses that grow uniquely where there are interesting claims and IOUs to what really happened. It certainly wouldn’t be the first person, but there was a cast of characters on all sides—not just Ricky but a host of other athletes and celebrities and friends and all that.

Life’s No longer a Beach

There’s a couple dynamics going on simultaneously. First of all, Mark and Brian and I were only maybe five degrees off in our vector, in our path for the business, in our intentions for the business, our expectations. I wanted to be over here and they were just over there. It wasn’t bad. So it’s not a big gap at first, but we went six years and stayed on those same vectors. We weren’t mature enough to have the difficult conversations to bring it together, to reconcile our differences. We would just go our separate ways if we had differences and just carry a grudge or whatever. So that built up to the point, because of our immaturity, it was kind of an insurmountable gap, and it really started to weigh on our relationship.

We were all about fun. We were all about just stepping out and being totally irreverent. That side of it we were decent at, but we didn’t have fiscal responsibility.Jeff “Beaver” Theodosakis

When we realized we had something is when you can’t even keep up with it. The opportunity is bigger than you can serve. When you’re in a situation like that, you’re trying to keep up, and that’s a signal. I can’t say there was this huge, huge event that changed everything. That comes later.

We did a deal with Laurens a couple years prior because we outgrew our ability to fund the business. It was growing at such a rate that we couldn’t…. So we did a licensee deal where we’d sell the stuff and market it, and Laurens would manufacture it, put it on a shelf, ship it, collect it, and pay a royalty to us. So it was a licensee/licensor relationship. It was working, and then there was some tension there and it wasn’t working. So we canceled the agreement that we wrote, and in the agreement, it says if you cancel it, you need to buy all the inventory and then pay all the outstanding debts. Which is normal, because they wouldn’t have license to sell it anymore. Thirty days later, according to the agreement, Laurens shows up with his attorneys and says, “Where’s my $1.2 million?”

I said, “We can do anything we want. We’re the most dangerous guys out there. We’ve got nothing to lose.”Mark Simo

I remember Brian calling me in tears and said, in his words, “I’m f--ked.” I go, “What do you mean?” He goes, “Everything’s gone.” I go, “What do you mean?” I don’t know. He had a bulldog named Sweetpea, and I thought maybe Sweetpea got ran over or something. He goes, “Laurens took everything. He put us in a position that we had to walk away or we would have screwed all of our vendors,” meaning everybody that built their shorts and their belt company and their T-shirt companies and all this different stuff. He said, “Laurens had us in a spot to where we have to walk away.” So I said to Brian, “I can grab my trailer and we can come steal a bunch of T-shirts and sell it over time at the swap meet for you to live.” So we contemplated that for a little bit. He said, “Let me call you back.” Then he said, “No, we can’t do that.”

Everything was a handshake situation back then. Contracts were for people who wanted to see the world differently. It was loose. At some point, all in hindsight, that separation—Laurens wanted the brand and wanted to continue on. I think Beaver was at a point where he was looking at how he wanted to engage going forward. Brain and I had our own ideas. So Laurens ends up with the brand. I think Beaver spent some time there with him. We actually went through a little legal battle.

We were just like, “Whatever, Laurens. We’re just stopping this thing.” He’s like, “Okay, but you guys wrote this agreement here.” So we were just negligent. We were all about the brand. We were all about the sizzle. We were all about fun. We were all about just stepping out and being totally irreverent. That side of it we were decent at, but we didn’t have fiscal responsibility. We didn’t have a financial backbone in the company that could help us hold the line. We’re 20-something-year-old guys having a ball. So we learned the hard way. Essentially, we had to sell the trademarks, Bad Boy Club and Life’s a Beach, to Laurens to satisfy the bank debt, which my father cosigned on a bank loan for us. My dad was going to get stung on that. So we had to give him the trademarks to pay off all the debts. And he did. He paid all the motocross magazines and surf magazines, all the debts. He’d pay everybody off. The bank, anyone we owed money to, and then we’re good. That was the deal.

Sometimes success is more challenging than failure. It’s different types of problems. Financing businesses, especially growing businesses, [isn’t] always easy. A lot of times we call it selling your soul to the devil, because [of] the way that you finance your business—and most businesses that grow quickly can’t grow organically. They can’t grow off of profits and sales. They have to reach further out and raise capital and take money in a unique way. So that was probably more so the case with No Fear, but at the same time, undercapitalized businesses make up for the lack of capital in creativity sometimes. That’s what we did.

Eventually you have to read the stuff [contracts], whether you like it or not. So I had an attorney who was up in Orange County in Newport. I went up and met him. He said, “Hey, look, you’ve got to give up. This is over.” I’m like, “What do you mean this is over? That’s my brand.” He said, “No, you don’t have money to fight. This isn’t a battle you’re going to win.” I think he kind of said that more because he knew I wasn’t going to be able to pay him, so he wasn’t going to volunteer any more legal work.

That’s where the real learning [happens], when you have consequence. When you fail. When you’re successful, you’re not learning, because you’re thinking it’s all you. But when you fail like this, those lessons really stick.Jeff “Beaver” Theodosakis

[The Simo brothers and I] kind of weren’t talking at that time. There were a lot of assumptions being made. There were a lot of people filling in the gaps that weren’t true. We still had a ton of respect for each other, and we still really liked each other, but we had insurmountable differences in business.

The lawyer could tell I was upset, and he made a comment when I walked out the door. He said, “Hey, if it’s any consolation, you’re the most powerful guy in the room now.” I said, “What does that mean?” He said, “Well, you’ve got nothing, so that means you’ve got nothing to lose. You can go do anything you want.” I remember driving home from Newport thinking about that going, “Huh. He’s kind of right. I can do anything I want. I’m out. I can do whatever I want.” So I came home and I talked to Brian about it. He kind of felt the same. When I explained it, I said, “We can do anything we want. We’re the most dangerous guys out there. We’ve got nothing to lose.”

The slogan “No Fear” came out in ’87. I’ve got some of the original No Fear T-shirts with Life’s a Beach on the front with No Fear on the back.

Mark Baagoe, who did the Life’s a Beach and the Bad Boy logos, was kind of off on a tangent, doing a lot of drugs. I’m not sure which one he was on, but it was a pretty hard drug, whatever it was. But he took a red paintbrush and he wrote “No Fear” on the wall of his art room. So it wasn’t even a plan. I just saw that and I go, “That kind of looks cool.” So the idea was born. Honestly, all these brands were ideas that came from creative people. We were just good at pulling all the pieces together and creating the energy around the idea.

It was a difficult time because my sister and Beaver were together. Mark and Brian were kind of fighting against Beaver, and I was really stuck in the middle on that one. They were going to go do their own thing, which was No Fear. Beaver couldn’t leave Life’s a Beach because his parents were the financing for Life’s a Beach. So to get the money and some other things back that Beaver and his family had invested in it, Beaver had to stay on for a year. They thought he was kind of a traitor, but Beaver couldn’t not pay his parents a lot of money. It was hundreds of thousands of dollars, so he couldn’t just say “screw it” and walk on his parents. So he was in a tough spot, so he stayed, and that separated those guys a lot. He did his year and then started prAna with my sister, which still is a really successful yoga/climbing/outdoor clothing [brand]. And those guys started No Fear and it took off like crazy. So I was kind of wearing Life’s a Beach on one side in my head and No Fear on the other and kind of trying to help both. I was trying to be neutral, but it was tough.

It was a lot of fun. I always say that Life’s a Beach was more of a cult following than a business. It included a lot of childhood friends.

I always use the phrase “We left with not even the shirts on our back.” Life’s a Beach, in the end, zero. But what we had was a suitcase full of lessons, and those lessons were the foundation for our future companies. When people come to work for companies that I’m part of, I put a lot of value on if they’ve had their own business and have failed, because that’s where the real learning [happens], when you have consequence. When you fail. When you’re successful, you’re not learning, because you’re thinking it’s all you. But when you fail like this, those lessons really stick.

It Begins

So a new chapter began for us, and for Beaver, too, I think. He created the prAna brand, which was more outdoor sports brand, rock climbing, and yoga-inspired stuff. He went one direction and had a lot of success doing that.

I’d see them every once in a while and give them a thumbs-up or whatever, but we weren’t talking. It was dark times. It was like a bad divorce. When you see people in the grocery store it’s like, which side are they on? It depends on the look they give you.

We walked in the warehouse and they had these three shelves with rolled-out fabric. 'Just pick one.' They were like bunks on storage shelves, and that’s where we lived. The shower was the hose up on the wall. That was the beginning of No Fear.Boris Said

We were kind of in two different worlds. I felt a little wounded, and Brian felt a little wounded, and I’m sure Beaver did too. But we split up. Ricky was still around, but he was now kind of exiting the scene from motocross because of his injury, which was sort of tragic. Beaver had taken up racing cars, local small stuff. So we kind of started looking at life after your day-to-day motocross ambitions of being the next factory star. The reality kicks in. We had a little business experience, started to grow, and ran with that.

I didn’t want to come in there and invest in it. I just said, “I’ll back you. I’ll push it as hard as I can.” I did.

Ricky and I were very good friends, and we ran pretty hard together on a lot of fronts. Ricky’s business was Ricky’s business and our business was our business, from the standpoint of how Ricky made a living and how we made a living. I think there may have been a bit of a perspective of what roles people played.

At that point, we were so all-in trying to get it going. We started with nothing, zero money. Of course we were friendly with Marty Moates, and he was working for a car dealership up in San Clemente. He called me one day and said, “I’m getting a divorce. I don’t know what I’m going to do. We’ll get together and work on this No Fear thing.” So he came over on day one, so it was Marty, Brian, and I at the beginning of the No Fear thing. Marty wasn’t quite the size ownership that we were. We brought in a couple of random guys when we got real desperate for money in the early years. This guy gave us a little bit of money. So we had about five or six of us altogether that had some money in it.

The first logo was exactly what was on the wall. It looked like a paintbrush. It said No Fear on the back and I put it on a T-shirt because that’s all we could afford. We couldn’t even afford to make shorts at that point. So I made a T-shirt. I put it on, and I was at the Dallas airport. I remember people reading it off my back. They were reading the logo off my back, so I said, “Maybe we got something here.” That’s when it started. But we didn’t have any money.

I got them involved with [car racers] Richard Buck and Rick Mears. I would give them Life’s a Beach and Bad Boy Club stuff back in the day. I was Indianapolis meeting with General Motors regarding stadium truck racing. I met Richard and I said, “No, you’ve got to take that Bad Boy Club thing off. You gotta put the No Fear on.” And that’s the year that Rick Mears flipped in qualifying, got in his backup car, went faster, qualified on the pole. There’s a picture of Richard Buck holding a notebook that said “No Fear” on it. It said, “Rick Mears has no fear. Don’t let your fears get in the way of your dreams.” So that whole thing got going, and then I got them hooked up with Jeremy McGrath.

That was ’91, my first year on Peak/Pro Circuit Honda. So that’s sort of when I met Surwall at the same time, but sort of just as an acquaintance. You probably remember when you first got your free T-shirt or whatever it was from somebody. Like, “Holy shit, I can’t believe this is even happening.” That was me in ’91, because first of all I’m just blown away that I even have a team ride. RJ called me to get the ride when I was at Loretta’s. We all know that story. Then to be invited to be on the No Fear team was another kind of an amazing moment. The first time I ever got any No Fear stuff, I had to meet up with Ricky and Stephanie [RJ’s wife] at their house in ’91—that’s when he gave me a full bag of No Fear shirts and all this stuff. It was pretty wild how that all first happened. That was my introduction to No Fear.

When you’re developing a brand, a story comes with it. The Life’s a Beach story was just about where we were in our lives, wanting to live at the beach and live this lifestyle. The Bad Boy Club thing came around with an attitude. Hey, we’re hanging with Ricky Johnson and that’s the baddest mother---er that ever swung his leg over a bike. I remember getting in a car with Ricky. He had gotten back from a race in Europe and he said, “You know something? I’m the fastest mother---er in the world.” That attitude, the confidence—Ricky gives an unbelievable speech about confidence. Everybody should hear that speech. It’s unbelievable. So the idea of the Bad Boy Club was basically finding that sort of Ricky Johnson-like hunger and fight to go do something. We were pretty impressed with the guy that maybe wasn’t the most talented guy that ever rode a bike, but definitely was the most hungry guy that ever rode a bike. That was sort of the Bad Boy Club story. That attitude was really attractive.

[The Simo brothers] were trying to help me get involved with some stock car racing with the Bechtel family, which is a pretty wealthy family. So I did a test. They signed me. We went to an awards banquet, the Busch Car National Awards Banquet. They announced that I was going to be racing for Rookie of the Year the following year. One of the Bechtel’s friends came to the room afterwards, and they thought that I was going to answer the door and then [they would] hit me with the fire extinguisher. Well, it hit my wife in the face. I thought it was going to kill her, because she couldn't breathe. It was crazy. Well, they all freaked out, and thought I was going to sue them, so they ended it. So because of the introduction from Jim Hancock and Jeff Surwall, I thought, “This could be the changing point of my life.” Stupid on my part, but anyway, I thought, “You guys made this introduction. This is going to be awesome.” I bought them both Rolex watches. I got a $20,000 contract. I spent 10 grand of it, bought them watches that said thank you for that, this, and that. The next week, the deal was done. They’re still wearing the watches, and I don’t have a deal.

Growing up, all my life was motocross. I raced motocross. I worked in a dealership, and then I actually became one of the youngest Honda/Yamaha dealers in the country when I was 21. I met the No Fear guys at the 1990 SCCA [Sports Car Club of America] run-offs. The year before, I met “Beaver” Theodosakis of Life’s a Beach, and he told me, “My partners are coming next.” I’m like, they must be the real brains of the operation, because he was kind of a crazy man. When I met those guys, we just hit it off. Then I started coming out. I lived in Connecticut at the time. That year is when they started No Fear. They were like, “Man, you need to come out and be a part of No Fear.” I just decided I was going to be a full-time race car driver, but I wasn’t really making any money, just scraps here and there. They said, “Well, you can come out here and work with us and race all you want.” So that’s what I did. I loaded up my pickup truck and drove out there. I’ll never forget. I got there at, like, one in the afternoon driving across the country. We went out to lunch. Then we came back and I’m like, “Where’s the house? Where do we go live?” They’re like, “You just live with us. We live right here.” We walked in the warehouse and they had these three shelves with rolled-out fabric. “Just pick one.” They were like bunks on storage shelves, and that’s where we lived. The shower was the hose up on the wall. That was the beginning of No Fear.

Boris is a living cartoon character, for one, so you’ve got to know that going into it. Great guy. Always there. Always supportive. Was really good at helping put deals together.

One of our first shirts was “Pussies Will Never Be Heroes.” That was actually a shot at Beaver. We were pretty angry in our split. It was more like a “Hey, we’re going to go for this. We’re going to go down this No Fear path, and we’re going to go out there and take this stand.” It was kind of an attitude. The shirt was kind of a statement. It was actually kind of funny. It wasn’t one of our better sellers, but it certainly was a comment.

Marty [Moates] came on board. I think he invested some money. Marty knew the Simo brothers because Mark Simo was his mechanic when he won the GP at Carlsbad. Laurens, who took them down, introduced Mark and Brian to Marty back in the day.

Marty, Brian, and I were living in the warehouse at the time, so it made sense. We were keeping the overhead low. It’s easy when you don’t have kids and a family. We lived there, and we’d go to happy hours. Back then we probably singlehandedly killed happy-hour snacks. We’d go and have dinner for happy hour and get some chicken wings for free. But we did that to get off the ground. Those are the sacrifices you make, but we had so much fun. We started going out a lot with Ricky and Marty, and then Boris comes into town. We’re all just having a great time. The fun generated a lot of energy.

Boris hated me. The story is so intertwined. Boris wanted to punch me in the face because he went to Binghamton, New York, to race an ATK, and he had an aluminum gas tank or something like that and they disqualified him. I was leading the 500 National Championship in ’87 or ’86 or something like that. He thought that I had him disqualified. I didn’t even know he existed. I didn’t know he was there. Why would I have him protested? So he resented me for years. So when I met him, one day he finally goes, “I’ve got to tell you something. I was going to punch you in the face for getting me disqualified.” I’m like, “What? Who are you?”

Yes, that’s true. I ran practice, and then they told me I couldn’t race. Someone told me he ratted me out, and I couldn’t believe it. I wanted to kick his ass, even though he was my hero. Pretty funny when we met ten years later!

The company had a couple moments. We were fortunate. We started giving some corner workers at the races T-shirts because they were volunteers. Well, those same corner workers at Willow Springs—I didn’t know it at the time—came to the Del Mar Grand Prix. They wore white pants and a white shirt, and they wore the No Fear T-shirts we gave them. A car caught on fire, and all these corner workers rushed out to pull the guy out of a burning car. It’s on the front cover of the San Diego Union, with a bunch of guys with No Fear on. So the headline of the San Diego Union reads “No Fear.” That was kind of the early things that started happening. It was really pretty quiet. We did have Robby Gordon with us. Ivan Stewart was involved early on. Back in those days it was all print ads. You’d run an ad in Motocross Action or Surfing or Surfer Magazine.

Mark managed upstairs quite well. He was very good in conversation no matter who you put in front of him, whether it be a Roger Penske or a Phil Knight or a Jim Jannard at Oakley. Mark was brilliant at doing that. He was a good strategist business-wise.

I went to the Pomona drag races with a guy, Bill Miller, who made all the pistons for the Top Fuel cars. John Force was just coming up. John Force walks into the trailer, and he introduces him to my brother and I and says, “These are the No Fear guys.” He goes, “No, I’m the No Fear guy.” Bob Glidden from the pro-stock class joined us; he was really well-respected. John Force is just this new, loudmouth kind of guy coming up. So Bob Glidden says, “Hey, Force, you’re going to support these guys, and you’re not getting any money, so put a sticker on your car.” So Force goes, “Okay.” He put it on top of his helmet. At the Pomona race, his car blew up and caught on fire. He climbed out of the top, and the first thing you see is a picture of him pushing out of the car with the No Fear sticker on the top of his helmet. Then we got involved with Rick Mears. Rick had that spin and win where he had spun and continued on and won the Indy 500. It was a crazy story.

I actually met Jeff Surwall first. I was living in Canada. I just had signed with Penske. I did some appearance or something for either Honda or Yamaha. They gave me a bike. I had to pick it up from a specific shop [Machine Racing], which was outside of Toronto. The guy that I had to pick it up from was Jeff. He was riding Canadian motocross up there. We got to know each other and it kind of went from there.

We were racing cars. IMSA came to Del Mar, and that’s the first time I ever saw what a prototype sports car looked like. Some of the guys like Hans Stuck were racing there, and I ended up racing with him at BMW and some of the other characters in car racing. There was a lot of crossover stuff in car racing. Robby Gordon was an ex-motocross guy as a young kid. We met Robby at the Del Mar Grand Prix. He was one of the early guys in the No Fear brand when we were looking to start finding these characters to get behind it.

I was helping get some distribution for them and doing some other things. They were like, “You’ve got to work here. We can’t keep up. We’re so damn busy.” I was always a little more … I don’t want to say logical, but I put a little more thought into some of the stuff. Mark was full speed ahead always, and his brother kind of would follow that. So I had a good place to fit in there.

During that period, people were taking chances. They were skydiving. ESPN had the X Games starting. All that stuff was converging, so those risk-taking things really symbolized the brand. Part of the story of the No Fear brand was just an evolution of the Bad Boy Club, going to the next level. Not just in your sports life, but also in your professional life. Take risks to live a better life. One of the things I thought [was] when you’re the No Fear guy, you kind of got to live up to it. That folds into allowing things to be a little bit more chaotic. The chaos actually creates an amazing amount of energy and creativity. So a lot of the great ideas came by just allowing the chaos to exist.

I became the national sales manager and sports marketing director. Everybody had, like, five jobs. I was the sales manager and the sports marketing director. It went crazy then.

I went to a couple supercrosses and Jeff introduced me to Ricky Johnson. I went out to California to Ricky’s house. He was living in Carlsbad then. I stayed with him for like a week and we did some training, bike riding, and stuff like that. He had introduced me then to Mark.

I remember watching Surwall as this privateer, and he was really fast. I knew exactly who he was. One of my first times out in California visiting they go, “We’re going to dinner with Jeff Surwall,” and I was like, “Oh my God, Jeff Surwall!” Then I was like, “Oh my God, he’s not really that impressive. He’s just a normal guy.”

Surwall and I had met each other a few times at races. He was sort of working at No Fear. Then we became fast friends. He and I are a lot alike. We had a lot in common, and we hit it off perfectly. Jeff and I, we started a great friendship at that time. When I first met Mark and Brian was probably one of the trips down to No Fear. I lived all the way up in Murrieta at the time, so it was a bit of a drive for us, but whatever I had to do to make it happen, I did. That’s when I met Boris. There was a bunch of other guys. Beaver’s awesome. He’s a good friend of mine now. We ride mountain bikes together and everything now. Beaver’s a huge mentor to all of us because he’s very successful. He stepped out of No Fear at the right time, built his own brand. It became very successful, and he’s still super successful today. He’s an unbelievable guy. So unique. He’s one of my biggest inspirations as far as business guys go. He’s cool.

When I went in there, I was working with Jeff on the sports marketing side. My first project was Adrian Fernandez on the IndyCar side of things. The No Fear guys were working with him. We were doing all the apparel: hats, T-shirts, stuff like that. I helped those guys execute the visuals of the IndyCar racing.

The Explosion

The biggest game-changer came in 1992. This was something we didn’t truly understand. In 1992, Ice-T, the rapper, wore a No Fear hat on CNN right after he had written the song “Cop Killer.” This is when the L.A. riots were going on. Surprisingly, you can still go to YouTube and look up Ice-T and “Cop Killer” and you’ll see the video where he’s wearing the hat. We had nothing to do with that. I don’t know how he found it. That’s when everything exploded. We didn’t come from the hip-hop world. We weren’t dealing with the inner city. We were dealing with coastal and inland motocross and surf guys. Along comes Ice-T and our world changed. Our sales went up by $100 million that year. We didn’t truly know why. It created a situation that we’ve been fortunate to take advantage of.

It was like, instantly after that, everybody had to have it. It started to become kind of a fad-like cult. All these kids wanted it. Everybody wanted it. It just grew and grew and grew after that.

I remember the Ice-T thing, and I remember on the front page of every newspaper story for a flood, someone put No Fear on their roof. That picture was in the news. It was like sandbags on their roof and the water was up to their gutters. That picture was on every news channel and everything. Also, Tom Rathman of the San Francisco 49ers and a few other guys put a sticker on their helmet, and they were circling it on Monday Night Football and going, “You can’t wear stickers on your helmet!” Then they fined them, and they kept writing about “why can’t you wear stickers?” Then Brett Favre and a few guys would wear the sticker and we’d tell them we couldn’t afford to pay the fine. You can’t do it. They’re like, “We don’t care, we’ll pay it!”

I took a plane and went to Haines. I got an appointment with the CEO and I said, “Look, I need your help. I need a million shirts a month. Can you get them to me?” The guy looked at me like I was crazy and he said, “Sure.”Mark Simo

After about eight months to a year, we actually moved out of the warehouse and we rented a house. We only had enough money for the house. We had air mattresses that I put on my credit card. Then RJ just bought a house, so he got all new furniture, so he gave us all his old furniture. Then we were living like kings, we thought, in this house with furniture and everything. But that was really the second year; ’92 is when it really, really started to go.

I had, like, four stores. I had North County Fair, which covered the north county. I had El Cajon, which was the biggest, best store for some reason, just really motocross and action-sports influenced. I think I had Bonita Plaza and even Mission Valley for a while. I had my plate full and over 100 employees on my end. It was cool. Mark and Brian didn’t put a lot of restrictions on me. We’re still friends, probably best friends today. We’ve been through the good, the bad, the ugly. I was there when they lost everything with Life’s a Beach. I was there at the beginning of No Fear.

Steve Wright is a really good friend now. He won the Baja 1000 on a three-wheeler overall back in the day in’85 or something. He had a No Fear store that did incredibly well in the El Cajon mall. By talking to him you wouldn’t even think he could walk and chew gum, but he was a marketing genius.

I met the guys back in ’79 when we were all running LOP Yamaha…. Good guys. Always had the highest respect for them.

Mark used me in his sales meetings all the time. How can this store in El Cajon sell a million dollars? He sells more than entire countries! Mark’s still doing pretty big numbers, but if you sold 50 to 100,000 you were considered kind of a B or an A account. But I just fully committed to those guys. Selling a million dollars at wholesale, that was a lot. So when we did 1.8, most of my sales—80 percent of my sales—were No Fear. I guess when I last checked, 80 percent of it was T-shirts. Yeah, we all want to remember the letterman jacket, but I sold 5,000 No Fear shirts a month.

Stevie [Wright], as well as many others, he got involved and was instrumental. I worked with him very closely showcasing what we were as a brand and a business. We all did one thing together: We all put on helmets. We all put on gear. We all lived our lives together but separately. Stevie was the one that initiated the first stores. We learned a lot about human nature and how people buy products, which we still live on today.

We started selling T-shirts, and at this point by the millions. We ran into a real problem. We bought every T-shirt we could find in California from all the distributors, so we were buying mixed and matched sizes and brands, and we couldn't keep up with the demand. I got totally lucky. I took a plane and went to Haines. I got an appointment with the CEO and I said, “Look, I need your help. I need a million shirts a month. Can you get them to me?” The guy looked at me like I was crazy and he said, “Sure.” He didn’t even ask me for any financial statements. He sent me a million shirts seven days later, and for three years, a million shirts a month came from Haines.

People saw us an apparel company. I never in my life had an affinity for apparel, which is hard to say. We put out the dollars that we put out—big dollars—in apparel, in a category that we were not very passionate about. So the marketing department called us the best merchandising company in the sports business, which may in fact have been a better deal.

I knew in Nebraska here we had a company called The Buckle. They’re one of the biggest retailers around the country as far as that kind of store. They’re really a first-class operation. I said, “Hey, guys, I want to handle the account with The Buckle, so I’m going to start knocking on their door and we’ll see where we go.” It took two years to get those guys to agree to do anything. When they finally did, we were running hard. They’re unbelievable business guys there. At that point, the brand had taken off and the brand was just selling everywhere in big, big ways. They jumped on No Fear and we did a lot of business at that time with them.

Another ex-moto guy. Again, growing up with Greg … Greg was involved in probably more on the business side of life. He was involved financially as well as from a management standpoint. Greg always remained very neutral in all of the above. He was a great guy. His life challenges, we all lived through. The fact that we’re still talking today is an amazing feat just from what’s happened to him in his life.

Obviously, I got hurt and I was back east. Then I moved back out here to California. It was early nineties. I was working at JT because of a nice offer from John Gregory, the original owner of JT. Then I stopped. It was a long drive, and I wasn’t sure how effective I really was there, because Mark Blanchard was there really carrying the weight. I just kind of opted out, thinking I wanted to make a bigger difference wherever I am and getting paid. I don’t like just making a check. So I was in limbo.

The NASCAR side of things was something that was my focus, and of course motocross. Then all of a sudden I was working and I had a little desk set up right beside Jeff’s desk. Jeff was still doing the sports marketing and transitioning out of the national sales manager position at that time and was taking on the sports marketing side of stuff. Next thing you know, there’s seven buildings. We had a production facility. We had a design facility. We had a sports marketing building. Those guys—Mark and Jeff and Brian—to me they were brilliant. They created some really cool brands.

I got a call from ESPN, and right at almost exactly the same time I saw this full-page ad on the back of a magazine out there called Competitor. It was like a Cycle News basically. On the whole back page it just had this color photo of a guy just diving off a bridge like a bungee jump, which was fairly new back then. It was just a bitchin’ picture, just this full-on like, “Here we go!” It just said, “Face your fears. Live your dream. No Fear.” I’m like, that’s cool. So I called over there, and somehow I got hold of Mary Moates. He was like, “Hey, what are you doing right now?” I’m like, “Nothing.” He goes, “You’re close by, aren’t you?” And I was. So I drove over there, and like 20 minutes later he’s taking me through the back with a shopping basket just going, “Hey, you like this shirt? Want this one? That one?” Before I had left, Mark and Brian and Don Whitmer, who was heading up their T-shirt stuff, they pretty much had a desk for me and a computer. I’m like, “I don’t even know how to use a computer though!” They’re like, “We’ll show you. It’s easy!” And I had a job.

David was a really, really talented designer. He kind of came through that era where Greg Arnett or Oakley [were] tweaking and making little bike parts…. Those guys were into really trick stuff. David had that knack. We were designing a line of auto-racing safety equipment. David would sit down and his nose would be an inch from the paper, and he would just be working. He designed driving shoes and the Driving Force line of driving stuff. He was a phenomenal, phenomenal designer.

Everyone wanted to dance with us. Everyone wanted to buy us drinks. Everyone wanted to hang out. It was just the energy and the synergy of it all was killing it. Somewhere along the way it got lost.Rick Johnson

I was in the art department, which was basically about the size of a tennis court with high ceilings. There was nothing really in there, just a few desks. Don Whitmer showed me how to use the Macintosh. I had a legal pad, jotting stuff down. I designed a few things and they were like, “Why don’t you do some cycling gear?” I had no idea what I was doing at all. A friend of mine that I had met at the San Diego Supercross, a guy named Todd Jacobs, he rode by one day. I told him, “Stop by and check it out. I’m making cycle gear. I have no idea what I’m doing. You’re a good cyclist—have you got any ideas?” And he did. He said, “Why don’t you just take some of the flannel stuff that’s real popular and make some jerseys and stuff out of that? Don’t try to be a full-on Castelli legit cycling company. You guys are edgy. Do something like that.” So I went to Florida to the sewing girl there. She made a sleeveless, a short-sleeve, and a long-sleeve cycling jersey all on the kind of popular material. I came into work the next day and Brian’s like, “Did you see the jerseys?” I go back there where they were and I’m like, “These are pretty neat.” It completely changed that whole category. It was all Lycra up until then, and then this made a little bit looser and more edgy. Then a few other companies kind of popped up. I think No Fear and Todd, it was actually their idea to just make a left and see if it worked, and it did.

[Bailey] was quiet. I was always a big David Bailey fan. I think I bought one of his helmets at an auction from the Trophee des Nations. His brother worked there, too, Mitchell. He was a lot more talkative. David was always nice. He was more to himself. He was more of an introvert than an extrovert, and most people at No Fear were extroverts.

I ultimately left in ’97 after watching triathlons. I decided, “I want to do that now.” I think they went from doing okay to, like, $100 million in a year or something like that. I’d just be sitting there trying to think of an idea, and then [Major League Baseball Hall of Famer] Reggie Jackson would come walking down the hallway.

David was designing bicycle stuff. He designed some 100% graphics. David’s always been really sharp. He did a couple different things down at JT. David, I think, has probably got one of the coolest hands and eyes that I’ve ever seen. Once again, they were at that point where they couldn’t put No Fear on enough shit. Bicycle shorts, swim shorts, they were everywhere.

Mark and Brian were racing cars, I think, at the same time. Then one time for fun at the end-of-the-year party they covered the entire parking lot, which was a pretty good size, with sand, and they put a huge dance floor and made a big stage, and they hired KC and the Sunshine Band. It was like, “Is this really happening?” And they had these little huts where you had to go and get a drink and everything. Everyone dressed up. Brian I think won the dressed-up contest. He had either no shirt or it was unbuttoned all the way down. He had a spraypainted gold necklace with an eight-track tape and super high shoes, just a full-on Saturday Night Fever deal. So they had it full blast. You never really knew what to expect when you went there, other than get your work done and have fun doing it.

I met David when I was, like, 13 years old when his dad was doing school. I’ve known him forever. He came in and he was doing design stuff. He’s always been super detailed and meticulous, even when he rode and everything. He was good. It probably didn’t fit his personality, because the place was a crazy mess most of the time. He definitely liked structure. He was great while he was there, but it’s oil and water with his personality and the way it was there.

Everything hit. A lot of it was the synergy of everybody. Collectively, there was nothing we couldn’t do. We could walk into a bar and run the place. We could go to a race and run the place. We could go anyplace. It didn’t matter how much money somebody had or if somebody had more money than us or nicer cars or whatever. Any time we all showed up—and we all showed up 100 percent—we ran the place 100 percent. Everyone wanted to dance with us. Everyone wanted to buy us drinks. Everyone wanted to hang out. It was just the energy and the synergy of it all was killing it. Somewhere along the way it got lost.

I was always amazed that I would go to work in the morning and 600 people would follow me.

I think it went from 1 million to 5 to 25 to 105 to 145. So those years were rapid growth.

I think we used to call it organized chaos. When you put youth, energy, and enthusiasm in a room you get all of the above. That will always transcend time and people in any business, and we had an abundance of it.

Thank God it was the nineties. I think half those guys got their wives out of the chicks they hired. Of course, they’re all divorced now. I would say they were certainly ripping tear-offs out of there. I was a little too young to be involved in that part of it.

No Fear Moto Begins

I always kind of played around with the gear and thought it could be better. When it really came together was with Jeremy [McGrath] and Travis [Pastrana] and a bunch of the guys I had. They would wear No Fear clothing twenty-three and a half hours of the day, and then a half an hour of TV at the race they’re wearing Fox or whatever. I’m losing it because I have stickers but I don’t have any control and I’m not getting any exposure.

Jeff Surwall was in charge of all things motorsports. He was similar to me. He saw a problem with the brand. He wanted to get into more technical equipment and authenticate the brand by making a good line of motocross gear. That was right in line with my thinking of coming up with higher price point, higher-quality products that were more designed to support the brand. So I said, “Jeff, if you want to take that, let’s go ahead and do that.”

I just said we’re so involved in the sport, but we’re just a sideline to it. I knew what the guys were making, salary-wise, and I knew that Jeremy’s deal was coming up, Travis’s deal was coming. I just kind of said, “I want to do this.” The brothers said, “It’s too expensive. We don’t really want to do it. We’re doing the clothing.” For me, the sports marketing end of it had gotten to a point where it was just more stickers and more T-shirts on guys. There was nowhere to go with it.

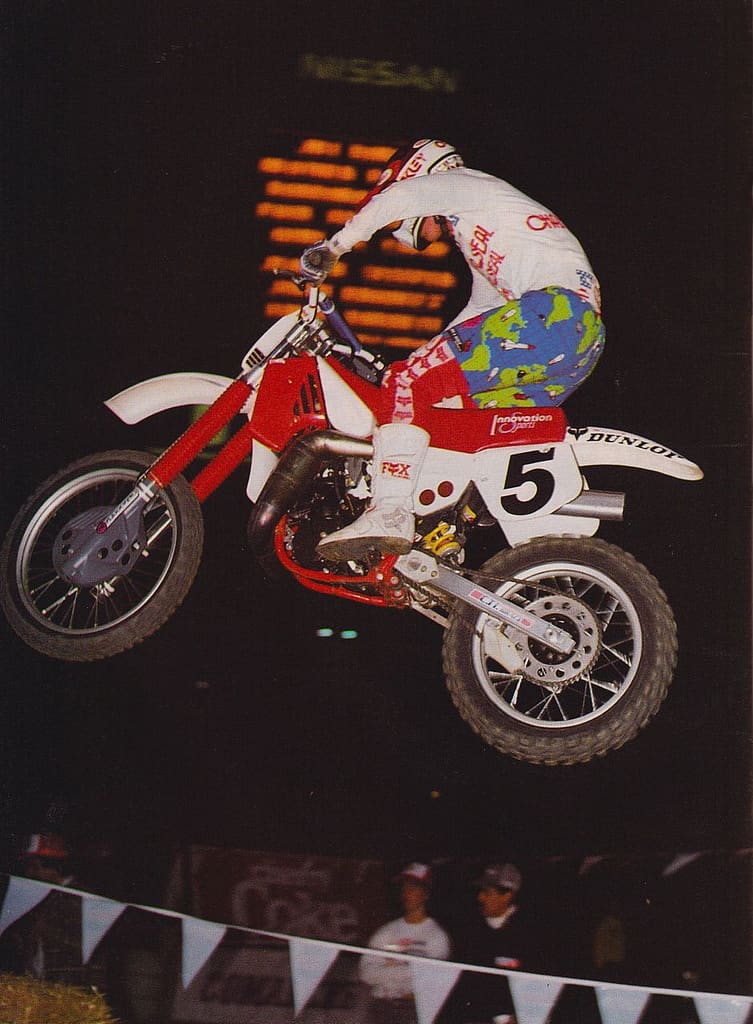

The way I remember it is … of course at the time I’m sort of on top of the world with Fox. I’m winning races. I had just transitioned out of that Suzuki deal in ’97 and onto Yamahas in ’98. I was still wearing Fox. Then Jeff came up with, or we all sort of agreed upon, but we came up with that new No Fear symbol. In fact, Jeff came to me with the gear idea and I said, “Of course!” Everything we did at that time was gold. How could I say no to that? Then of course I had the platform to sell it, because I was out there winning races and I could wear it. What I did legally to get out of my Fox contract, I had a clause in my Fox contract that said if I majorly changed my schedule, then my Fox contract basically had to be renegotiated or whatever. That was the year I switched to supercross only. Then we came up with a business plan with No Fear. Of course, looking back, obviously I made some mistakes in doing that in the beginning, because I got in a lawsuit with Pete Fox over bonus structure and stuff like that, which first of all scared the crap out of me because I’m a young kid and I’d never been in any sort of legal mess at all. So we got all that straightened out and No Fear was good.

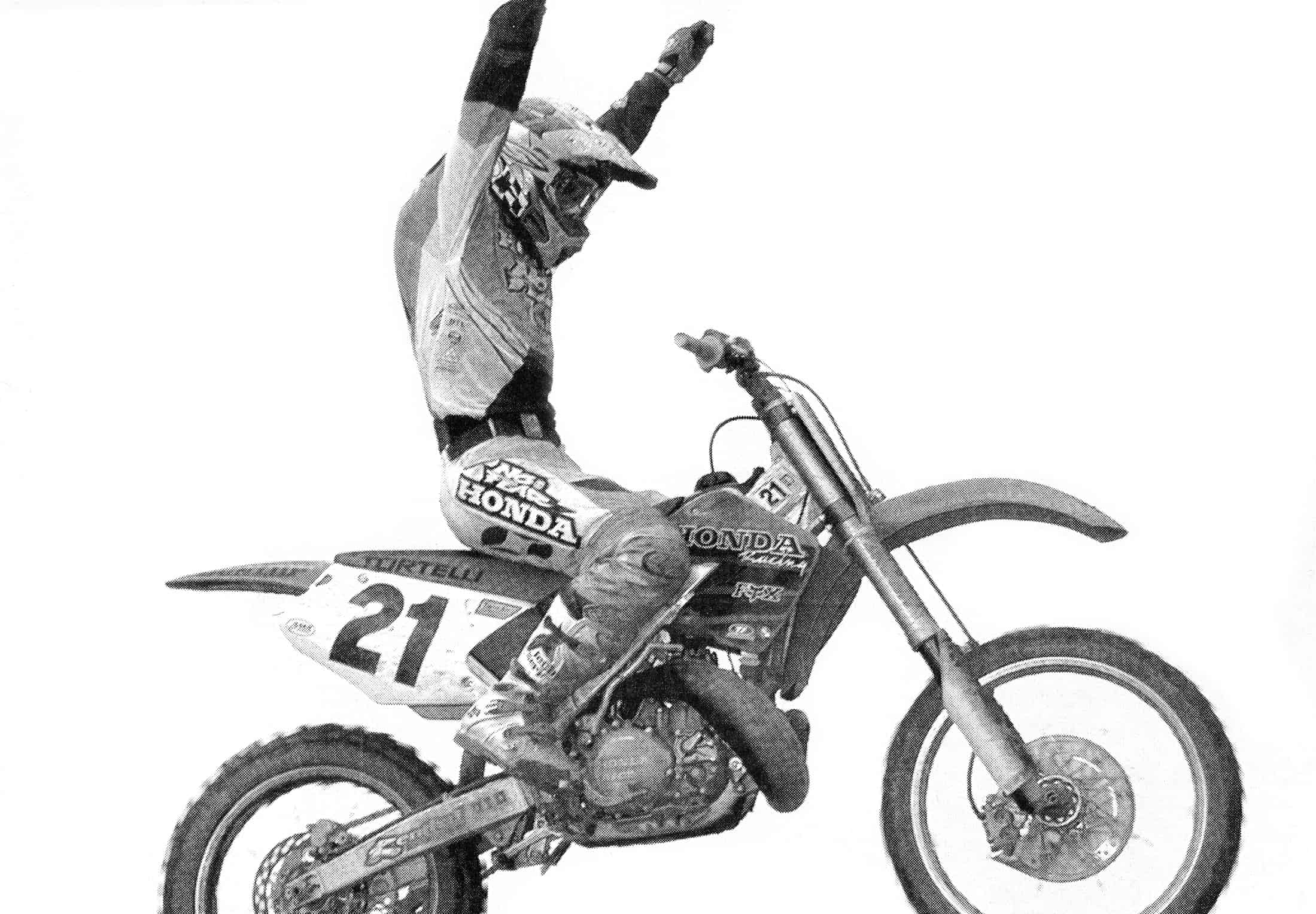

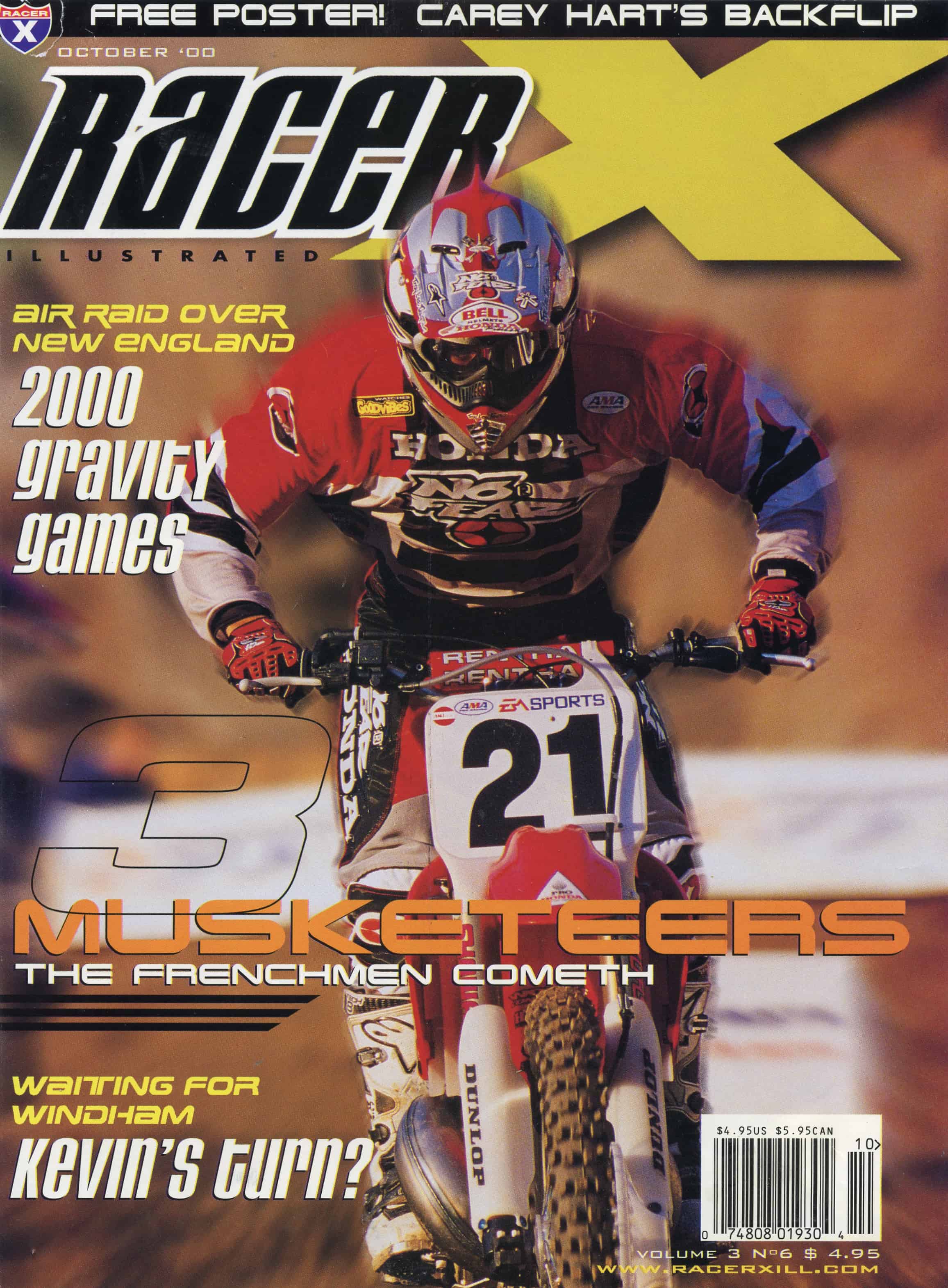

I talked to Jeremy. Paula [my wife] and I decided to put our money in. Jeremy’s like, “I’ll do it.” So he got involved, and for him, it was when he was going to supercross only. So I had to get some outdoor guys and things. The timing was great. It was hard to not want to do it when I had him and I was about to get Travis. Then I got [Sebastien] Tortelli, and I was already doing [Kevin] Windham’s stuff. So I picked those guys, and then Stefan Everts. We got the cream of the crop. It was a big risk, because gear is a tough business, but you’ve got a lot stacked in your favor. So full steam ahead. I was like, we’re going to run full-page ads every month and try to be kind of like AXO and make the gear look even better than it was, do amazing photos. I got a buddy of mine from France that I’ve been friends with forever, Jerome Mage, who did the designs, and they looked great. Jeremy loved them. The riders loved them. We did some technical, creative stuff. Gear was kind of stale, so we did some cool things. Adjustable waist and Kevlar in the knees. Just a lot of little things to help market it and help make it a little better. It was accepted and it took off.

Adam and Kyle Petty were the big thing in NASCAR. We had a design facility. We had a sports marketing building. Those guys—Mark, Brian, and Jeff—to me they were brilliant. They created some really cool brands.

In ’99, when I came to the U.S., I mainly talked to No Fear. I knew Jeremy’s family, and I was presented to Jeff Surwall early on. I wanted to ride with an American company, as the past French riders never were really accepted. On top of it, it was with Jeremy and Kevin, so it had a great wow effect. The gear had cool designs; Jerome Mage did it, so a little French touch! It was good for the time—tough pants and heavyweight jerseys. I remember loving the vented sets, especially at Daytona, but when I pull out of my boxes the few sets that I kept, I realized the cotton jerseys were so heavy. The gear has made an such improvement since.

Jerome was a big part, the designer. Jeremy had input on what he liked and didn’t like. At the time he had earrings and was dyeing his hair different colors. He was kind of cutting-edge but backing it up with results, so it was fine to do whatever you want to do. I knew what I wanted. We all worked kind of together on it.